Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biochemistry

People with allergies have special set of immune cells, researchers find

Cells could serve as indicators of the efficacy of allergy therapies and provide new drug targets

by Michael Torrice

August 2, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 32

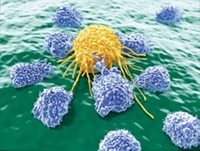

People with allergies sneeze, wheeze, and scratch because their immune systems have added pollen, dust, mold, or other allergens to the list of foreign threats to attack.

Researchers now report a distinct group of human immune cells that are associated with those allergic reactions (Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam9171). These cells could act as biomarkers for the effectiveness of allergy therapies while also providing possible new drug targets.

“For the first time, we have a way to distinguish between bad cells involved in allergies and the good ones involved in fighting infection,” says Erik Wambre of Benaroya Research Institute, who led the research team.

The allergy cells his team identified are a subset of type 2 T helper (TH2) cells, which trigger the immune system’s response to both allergens and pathogenic invaders, such as bacteria and parasites.

Wambre and his colleagues wanted to understand what made the TH2 cells that respond to allergens different from others. Immunologists have been trying to do this for a while, says Wayne G. Shreffler, chief of pediatric allergy and immunology at Massachusetts General Hospital. But it is hard to isolate the extremely rare cells that respond to a specific allergen from other immune cells, he says.

In the new study, Wambre’s team used a molecular probe to physically separate TH2 cells targeting allergens from alder pollen, peanuts, and other sources from a collection of allergy patients’ immune cells. The researchers analyzed the proteins expressed on the surfaces of TH2 cells from 34 people without allergies and on cells collected with their probe from 80 allergy patients. Of the more than 150 surface proteins the scientists profiled, five differed in the allergy patients’ cells: Two had lower expression levels and three had greater ones than the cells from nonallergic patients.

The scientists called the cells with this specific collection of surface proteins TH2A cells. Although people with allergies have large numbers of TH2A cells circulating in their bodies, people without allergies do not, Wambre says.

To demonstrate that these cells could serve as biomarkers, the researchers studied TH2A cells from peanut-allergy patients enrolled in a trial of an immunotherapy to desensitize them to peanut allergens. Wambre’s team found a correlation between a drop in the number of TH2A cells and how well a patient became desensitized to peanuts.

“We are on the verge of the first U.S. Food & Drug Administration-approved treatment for peanut allergy,” Shreffler says. “Yet there is still a lot of heterogeneity in how people respond to the treatments.” Looking for changes in the number of TH2A cells could help doctors and researchers determine which patients are likely to respond to such therapies, he says.

In addition to the prognostic potential of these findings, discovery of TH2A cells “may change how we treat allergic diseases in the future by providing new drug targets,” says J. Andrew Bird, director of the Food Allergy Center at Children’s Medical Center and an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Wambre points out that his team has already identified a couple biochemical pathways that are unique to TH2A cells. “Maybe drugs that target these pathways could stop or destroy these cells,” he says.

This article has been translated into Spanish by Divulgame.org and can be found here.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter