Advertisement

In early 2016, the financial communications firm LifeSci Advisors found itself with a public relations crisis on its hands. An article in Bloomberg had skewered the firm’s decision to hire female models to serve its client party at the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco. The cocktail waitresses themselves were enough to stir trouble, but LifeSci Advisors doubled down on the gaffe by claiming the move brought necessary gender diversity to an event for the mostly male investors and executives who attend the annual conference..

In brief

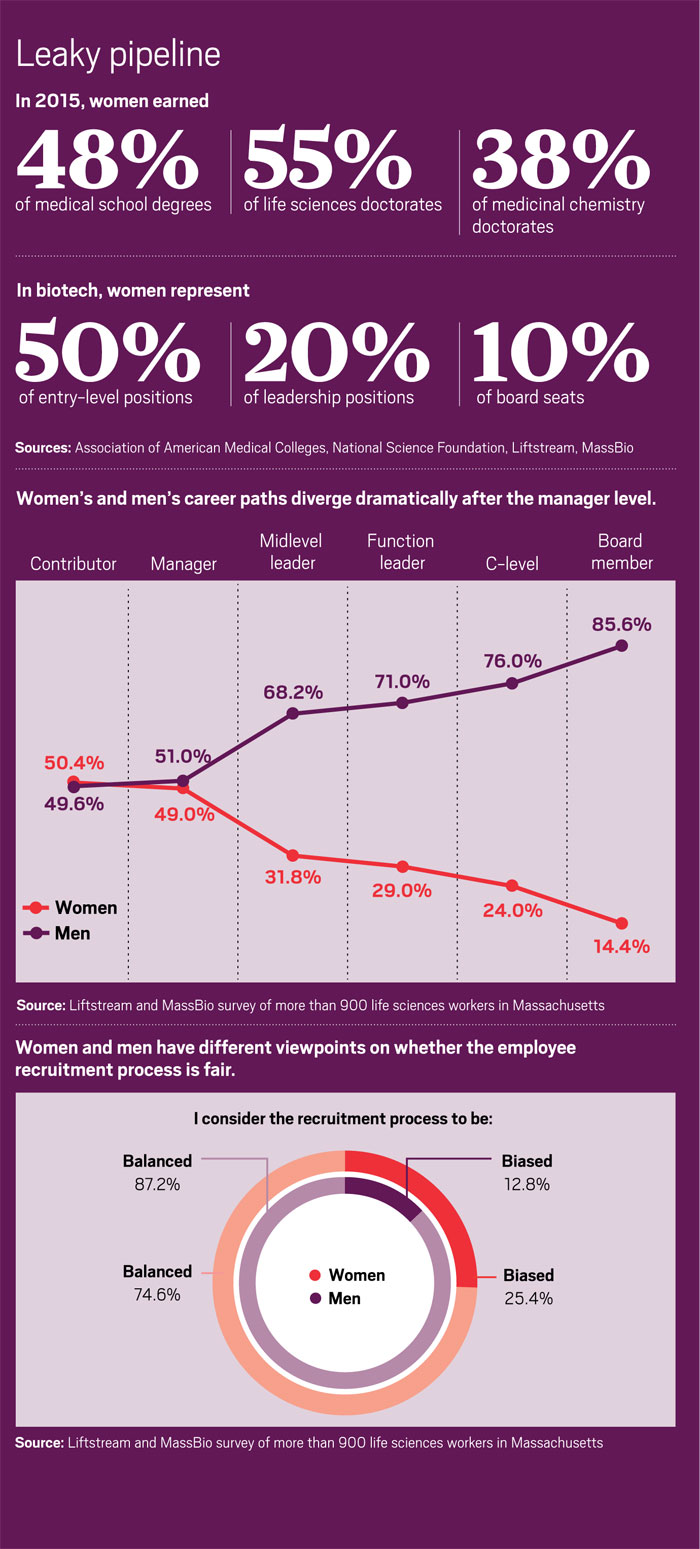

Women are entering the drug industry at the same rate as men, but few rise to leadership positions. Amid a push to get more women on boards and in C-suites, C&EN talked with senior female executives about what initiatives are effective and what more needs to be done to fix the leaky pipeline.

Advertisement

Mention that party to women working in biotech today and the reaction is nearly universal: an epic eye roll, often followed by an audible sigh.

Their exasperation is palpable. How could an organization have been so tone deaf? Dig deeper, and you’ll find the subtext of those sighs: Here we are, in 2018, still needing to talk about the biotech industry’s gender diversity problem. Although the #metoo movement has reinvigorated the discussion, it can also feel like it’s going in circles.

"We always talk about what women can do. We have to change the conversation to what men can do.”

—Rosana Kapeller, CSO, Nimbus Therapeutics

The issue is well defined. Women and men enter the workforce with advanced degrees in medicine and science at nearly the same rate, but for some reason, many more women either drop out or hit a plateau in their careers.

Whether it is the paucity of women on company boards, the slow progress in getting women into leadership positions at big pharma, or the alarming absence of women as scientific founders and research heads, the numbers just aren’t there. Women of color are missing almost altogether at the upper echelons, a problem the industry has yet to even begin reckoning with.

Since that infamous party, organizations have amped up the number of initiatives meant to help women ascend the ranks. Networking for women, board training for women, mentorships for women—programs have proliferated.

But are they actually moving the needle on gender diversity in biotech?

To try to answer that question, C&EN talked with nearly two dozen women working in the biosciences—in academic drug discovery, biotech start-ups, and big pharma. They shared some of the pain points in their careers, as well as concrete ideas for moving more women up the ladder.

Some are optimistic that women entering the workforce now will be the true beneficiaries of a society that values an inclusive work culture. Others worry that change is simply too slow or unfolding in a way that doesn’t get at the fundamental reasons so many women drop out of the pipeline.

If increasing women’s representation in biotech turns into a box-checking exercise rather than an overhaul of the industry’s culture, any progress won’t hold. After all, as Abbie Celniker, partner at the life sciences venture capital firm Third Rock Ventures, puts it, “The goal isn’t to create diversity for diversity’s sake. The goal is to have an inclusive culture that can be measured by diversity.”

The business case for an inclusive workforce is strong. Often-cited research by the nonprofit Catalyst found that Fortune 500 companies with the best gender representation on their boards also generated a significantly higher return on sales and equity than those with few or no women.

When biotech companies take the time to cultivate inclusive work environments, two good things happen, says Susan Molineaux, founder and CEO of the biotech firm Calithera Biosciences. The first is that R&D becomes more efficient “because people can speak up; they feel safe,” she says. The second “magical thing is you retain your talent.”

Moreover, women make most health care decisions for their families, and yet the industry has “so few women who are in the C-suites of companies,” says Christi Shaw, president of Lilly Bio-Medicines. It simply isn’t good business to exclude those voices when setting the drug development agenda. “It’s a disservice to the health care system that we don’t have that diversity,” Shaw says.