Advertisement

GERALDINE RICHMOND

In brief

The 2018 Priestley Medalist, Geraldine (Geri) Richmond, made her mark with insights about how molecules behave at the air-water and oil-water interfaces, but her contributions extend far beyond the lab. She helped found COACh, an organization dedicated to giving women skills for successful science careers; served on the National Science Board; and traveled as a science envoy in Southeast Asia for the U.S. State Department. A commitment to helping others ties it all together. Read on for C&EN’s profile of Richmond as well as the award address she’ll deliver at the ACS national meeting in New Orleans.

More

Geri Richmond is on a mission. “Right now, I feel this urgency to give other people the insights I’ve gained,” she says. “I just have a head full of stuff that could be of value to people who want to do something similar.”

“Something similar” encompasses many things. Richmond, a pioneer in a field whose importance is still growing, is responsible for fundamental discoveries about how water molecules behave at water-oil and water-air interfaces. She has also spent more than three decades as a chemistry professor at the University of Oregon, served on the National Science Board, and been president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She founded and continues to serve as chair of COACh, an organization dedicated to helping women advance in science and engineering careers.

In recognition of all that—and more—she is now the winner of the 2018 Priestley Medal, the American Chemical Society’s highest honor.

Richmond will put her Priestley on a shelf alongside the National Medal of Science, the Joel Henry Hildebrand Award in the Theoretical & Experimental Chemistry of Liquids, the Davisson-Germer Prize in Atomic or Surface Physics, and other signifiers of her successful career. They honor her scientific accomplishments as much as her work as a mentor, adviser, and colleague. These days especially, Richmond is passing on her insights as she strives to help other scientists succeed in their own careers.

Advertisement

Related: Geraldine Richmond named 2018 Priestley Medalist

The back office

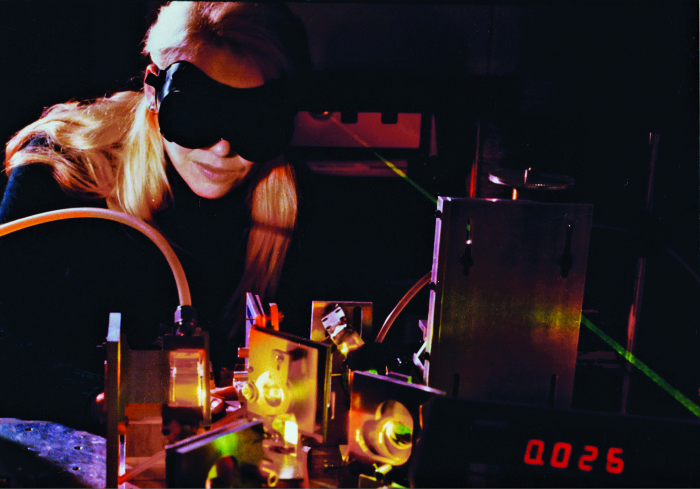

Richmond’s office is a little hard to find. Tucked away on the second floor of the university’s physics building, you have to go through her research group’s wet lab, past her students’ offices, then through a second room crowded with beeping lasers, tools, and other sensitive instruments.

Finally inside, you’ll find the office crowded with photos of her family and past group members, memorabilia, and of course, those awards. Each of her sons spent part of the first year of his life in this office, playing in a playpen while Richmond worked. On one shelf sits a piece of machined aluminum and stainless steel, the first thing she made in a metal shop.

That was at the University of California, Berkeley, where she got her Ph.D. under George C. Pimentel, who won his own Priestley Medal in 1989. Richmond remembers learning her way around that shop.

“I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” she says. “I had never used a metal machine shop before.”

The location of Richmond’s office says a lot about her relationship with her trainees. She is not a micromanager. She’s like Pimentel in that way. During Richmond’s tenure as a grad student in his lab, he spent almost all his time in Washington, D.C., working as deputy director of the National Science Foundation. Richmond, a big proponent of giving back to the science community, is gone a lot, too.

Take one three-week stretch in February as an example. Richmond spent four days in New Orleans, where she gave the keynote address at a meeting of scientists who’ve been studying the aftermath of the disastrous 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. She came home briefly, then traveled to Syracuse University to deliver a lecture, before flying to tiny St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn., to give a talk to chemistry majors. A few days later she was off to a National Science Board meeting in D.C. and then to Tunisia to work with women scientists there.

Richmond was in her lab for four days. Her students have to be self-reliant, a lesson Richmond learned from Pimentel. But that doesn’t mean she’s not paying attention.

“They may think that I just walk into the office and walk out, but I keep a close eye on them,” she says. “When I can tell that something’s not going right, that’s when I need to connect with them.” It could be a problem with their work or something outside the lab, but when she senses that they’re struggling, she steps in to help them find a way forward.

That she keeps a close eye on her students shows in unexpected ways. In February, Richmond’s newest graduate student, Rebecca Altman, passed her qualifying exams and officially advanced to Ph.D. candidate status. The Richmond lab has a long tradition of celebrating important occasions by “pieing” the person of honor.

Related: Geraldine Richmond among chemists to win presidential science awards

Altman took her cream pie in the face with good humor. Another student, Brandon Schabes, had a second pie waiting, this one with Richmond’s name on it. But before he knew what was happening, he was the one with cream dripping from his hair, and Richmond was holding an empty pie tin, laughing. She knows their tricks better than they do.

Richmond acknowledges her hands-off style of management doesn’t work for every student. “I tell them I’ll guide you until you take ownership. And when you take ownership, I expect you to drive it largely yourself,” she says of students’ Ph.D. projects.

“She was very good at releasing the reins and letting you explore the areas you wanted to explore” and then having you bring those ideas back to her, says Derek Gragson, a physical chemist and associate dean at California Polytechnic State University who got his Ph.D. with Richmond. He says he has drawn from her example in learning how to be an adviser.

It’s that hands-off approach that attracted fifth-year doctoral student Brittany Gordon to Richmond’s lab. Gordon did extensive self-directed research as an undergraduate at New College of Florida. She became aware of Richmond while she was researching solar cells in Shannon Boettcher’s lab at the University of Oregon as part of the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates program. Richmond founded the REU site at Oregon in 1987; it’s the longest-running REU site in the country.

Gordon knew she wouldn’t need a “helicopter” adviser to keep her motivated but also that she has a bad habit of falling down rabbit holes. She says that’s what makes Richmond a great adviser: She lets Gordon take the lead but steps in when she thinks Gordon is getting sidetracked.

Gordon sees it as preparing for her own career as a principal investigator. “We’re not going to have someone holding our hands the rest of our lives,” she says.