Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Chemical Communication

Geosmin could be a good bait for mosquito traps

Study demonstrates that beet peels, which contain the compound, could be used as a low-cost mosquito bait

by Laura Howes

December 12, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 48

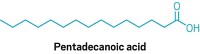

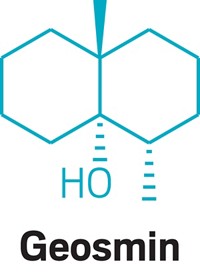

If you’ve smelled the musty odor of moist soil or the air after a rainstorm, you’ve smelled geosmin, a terpene produced by soil bacteria and cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). Although scientists don’t know why humans have developed such a sensitivity for the scent, it seems some insects can also detect it. In Sweden, the US, and Brazil, researchers have now found that the yellow-fever mosquito Aedes aegypti is attracted to geosmin. The scientists demonstrated that the odorant could be useful in mosquito traps that help control the spread of disease (Curr. Biol. 2019, DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.002).

In 2012, Marcus C. Stensmyr of Lund University was part of a group that found that the common fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster sniffs out and avoids geosmin because the compound is produced by molds that make fruit unsuitable feeding and breeding sites (Cell 2012, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.046). Because of the group’s finding in fruit flies, Nadia Melo, a postdoc in Stensmyr’s lab, wanted to see if geosmin also acted as an A. aegypti repellent. However, she found the opposite was true: the mosquitoes flew toward the fragrance. At first, Stensmyr says, that was a bit disappointing. But with some testing, the researchers soon worked out what the mosquitoes were using the molecule for and why that might make the molecule good for controlling mosquito numbers.

For mosquitoes, geosmin smells like the perfect place to lay eggs—possibly, Stensmyr says, because cyanobacteria are a good food source for mosquito larvae. To test if this finding could be turned into something useful, colleagues at Florida International University set up traps, some containing the odorant and others without it, across Miami. Mosquitoes preferred to lay their eggs in traps baited with geosmin, and that got Stensmyr thinking.

“I’ve worked with geosmin a lot, and every time I smell it, the only thing I can think of is beetroot,” Stensmyr says, using the European term for beets. “To me it smells absolutely like beetroot.”

So Stensmyr’s team went back and found that A. aegypti mosquitoes also show a preference for beets, specifically the peel, which contains much more geosmin than the pulp. Colleagues at the Federal University of Alagoas in Brazil made and tested a low-cost trap consisting of a water bottle, filter paper, and beet-peel extract as bait.

Greg Pask, an expert at Bucknell University on how insects detect and respond to smells, says he was excited to see “such a detailed study” when he first saw this work as a preprint earlier this year. “The fact that beetroot peel, largely a waste product, can be just as effective at attracting mosquitoes is a delightful result with real promise as a sustainable control strategy,” he says, “as long as people continue to eat borscht and beet salads”

Stensmyr says he plans to optimize the beet-baited traps with his Brazilian colleagues and then test whether they meaningfully affect mosquito populations.

But there’s also more to learn in the lab, he says, including how exactly A. aegyptidetects geosmin and whether other insects also detect the compound.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter