Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Chemical Communication

Soap scents versus mosquitoes

It’s no DEET, but your soap choice can change your attractiveness to mosquitoes

by Laura Howes

May 15, 2023

Mosquitoes. They’re annoying pests and can spread disease through their bites. As they seek out a meal of human blood, female mosquitoes use a variety of chemical cues to zero in on their next target. So if you’re a mosquito magnet, new research from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University suggests paying attention to your soap choice (iScience 2023, DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106667).

A team of researchers, led by chemical ecologist Clément Vinauger, asked four volunteers to wear fabric sleeves that could pick up each person’s individual odor. They then used these fabric sleeves to establish how attractive the smells were to female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

The volunteers then washed with four different soaps, and after each soap was used the researchers took more samples and tested what the mosquitoes thought of the soap-modified skin smells

The mosquitoes became more attracted to some, but not all, volunteers after they washed with Dial, Dove, and Simple Truth soaps. The mosquitoes were put off when any of the volunteers washed with a coconut-scented soap from the brand Native.

The team identified potential chemicals in these soaps that seemed most responsible for attracting or repelling the bugs and then built scent blends to test their hypothesis. In further tests, the mosquitoes turned their noses up at the researchers’ mix of benzyl benzoate, benzaldehyde, and γ-nonalactone.

It’s a small study, says Marcus Stensmyr, who studies insect olfaction at Lund University, but “the premise of the paper is quite fun.” Stensmyr isn’t surprised that soap altered the volunteers’ smells; after all, you’d hope that would happen. But it’s more evidence to support the idea that compounds that smell pleasant to humans could help to help protect us from the pesky insects in the future, he says.

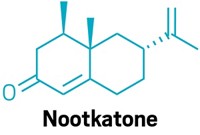

In 2020, the US EPA approved the chemical nootkatone, found in grapefruit skins, as an insecticide and repellent that protects against biting pests such as ticks and mosquitoes. Stensmyr says that building up a database of mosquito scent preferences could help design future mosquito-repelling perfumes or pleasant-smelling insect traps.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter