Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Infectious disease

Can H5N1 bind to human-type receptors? The answer is complicated

H5N1 transmission data in new paper reassuring but questions remain around receptor binding assay data

by Alex Viveros

July 9, 2024

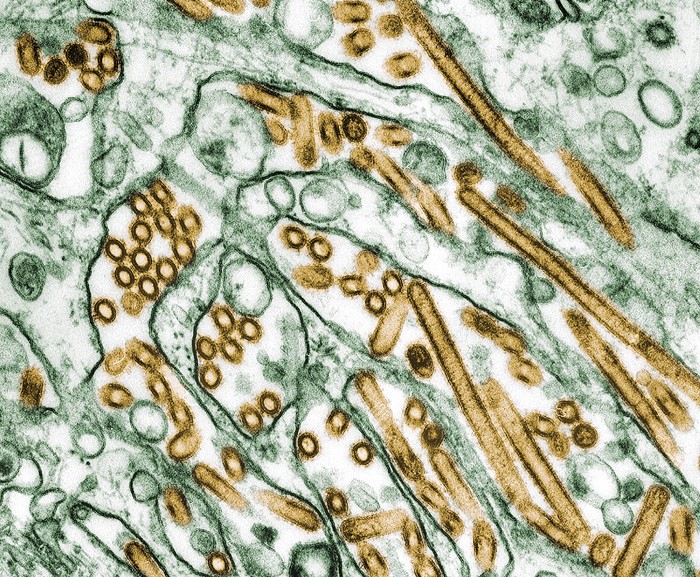

When a highly pathogenic strain of H5N1 influenza virus emerged in US dairy cattle in March, scientists around the world had a slew of questions about the virus’s characteristics. In a new paper published yesterday in Nature, virologist Yoshihiro Kawaoka’s group at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and collaborators assessed the pathogen (2024, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6). But not everyone agrees with all of the researchers’ conclusions.

To understand transmission, the researchers infected mice and ferrets with an H5N1 virus isolated from a dairy cow. The team found that the virus could spread to small mammals through contaminated milk and that a lactating mouse could infect her feeding pups. In ferrets, the virus did not efficiently spread through respiratory droplets, signaling that H5N1 has not taken advantage of one of the most worrying routes of transmission in mammals.

“I don’t see anything that is raising alarms for me that we’re going to be seeing expanded human infections or transmission events,” says Mark Tompkins, a viral immunologist at the University of Georgia. “The ferret transmission data, in particular, is very reassuring.”

Multiple scientists that C&EN contacted described the work as important to understanding the properties of H5N1 in cows. But they were unconvinced by one of the paper’s additional claims, which suggests that the H5N1 virus circulating in cattle may have picked up the ability to selectively bind to sialic acid receptors along the human upper respiratory tract. Such a change has long been known to make influenza viruses better at spreading among people.

The scientists say the receptor binding assay that Kawaoka’s group used has limitations compared to those employed by other groups. A recent preprint and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that the virus has not developed signs of adapting to human-type receptors. Other groups also report that they have found no evidence of a change from the virus’s preference for avian-type receptors but that their data has not yet been published.

“We’ve collaborated with two different groups that have provided the same bovine H5N1, and there is no hint of specificity change,” says James Paulson, a biochemist at the Scripps Research Institute who studies how viruses recognize sugars on the cell membrane. “Not a shred.”

In an email to C&EN, Kawaoka says differences between his assay and those of other groups could explain the contradictory data. “Our system may be more sensitive in detecting virus binding to sialic acid-containing glycoconjugates because of the high density and multivalency of sialyloligosaccharides, which may explain the apparent difference in results,” he says. Under those conditions, the group reported that their H5N1 isolate binds to both human-type and avian-type receptors.

Researchers who study H5N1 say other groups are expected to publish data soon describing the receptor binding profile of the H5N1 strain circulating in US cows.

“The animal transmission experiments in the mice and the ferrets are really top notch,” says Robert de Vries, a glycoscientist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. “But take their claim of human-type receptor binding with a pinch of salt.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter