Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Infectious disease

What you need to know about the bird flu outbreaks in cows

A strain of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus has jumped from birds to cows. Public health officials say the risks for humans remain low

by Priyanka Runwal

April 29, 2024

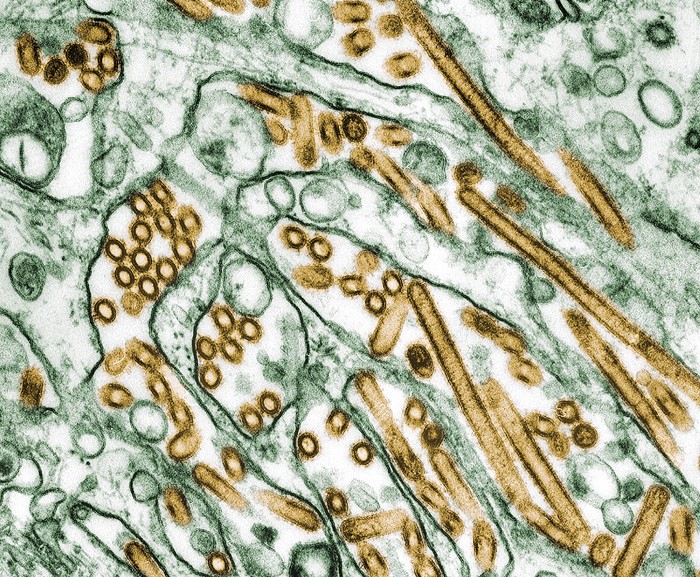

On March 25, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Drug Administration, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced a multistate outbreak of bird flu in dairy cows. A highly pathogenic strain of the H5N1 avian influenza virus is causing the outbreaks, and it’s the first time public health officials have detected the pathogen in cattle.

It’s a surprising find, says Richard Webby, an influenza virologist and director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals. “Typically, we don’t tend to associate these types of influenzas with cows.”

Although the virus commonly circulates in wild birds, and is deadly particularly for poultry, it has been infecting an increasing number of mammals since 2021 as it has spread across the globe. The virus has killed animals that may have eaten infected birds or come in contact with their droppings, such as foxes, bears, raccoons, skunks, elephant seals, and sea lions.

The outbreaks in US dairy farms have affected at least 34 herds in nine states—Texas, Kansas, Idaho, Ohio, Michigan, New Mexico, Colorado, North Carolina, and South Dakota. No cattle are reported to have died, and the disease is mild to moderate, says Andrew Bowman, a veterinary epidemiologist at the Ohio State University. Cows showing symptoms have fever, loss of appetite, and decreased milk production, but some are potentially asymptomatic, and those positive cases are therefore going unnoticed. How the virus is spreading from cow to cow is still a mystery, Webby says. On April 19, the WHO announced that it detected “high concentrations”of the virus in raw milk, so one possibility is that H5N1 may be spreading during the milking process.

So far, one person has tested positive for H5N1. That person, who worked at a Texas farm with sick cows presumably infected with the virus, experienced eye redness as the only symptom, according to the CDC. The individual was asked to isolate and given oseltamivir—an oral antiviral used to treat influenza’s symptoms. The CDC maintains that the risk of infection for the general public continues to remain low.

“But it’s a numbers game,” Webby says. “The more opportunities there are for interactions between an infected host and humans, the more spillovers we’ll get.”

What’s the USDA doing to limit the spread of H5N1 in cattle?

Under a federal order issued on April 24, the USDA requires lactating cows to be tested for H5N1 before any interstate travel. “You have to have a certificate of veterinary inspection in order to move animals across state lines anyway,” Bowman says. Adding the testing requirement is a great first step, he says. Any other H5N1 testing remains voluntary and is encouraged for animals that show disease symptoms. Reporting positive test results is mandatory, and the USDA recommends isolating sick animals for 30 days.

How widespread is the virus in cows?

Preliminary results from the FDA’s nationwide survey of commercially sold milk indicated that one in five pasteurized milk samples have fragments of the H5N1 virus. Bowman independently tested 150 store-bought milk samples and found traces of H5N1 genetic material in 58. The findings suggested to him that the virus was “more widespread that what we were giving it the credit for,” he says.

As of April 27, the USDA had detected 34 H5N1 outbreaks in nine US states. The agency also recently confirmed H5N1 in a lung tissue sample of a cow without any signs of illness among several other cows in the herd that showed symptoms. Such asymptomatic infections make it challenging for experts to determine how widespread H5N1 might be.

Is it safe to drink cow milk?

The FDA maintains that commercial pasteurized milk is safe to drink even with virus fragments present. In early tests, the agency recently confirmed that H5N1 genetic material found in pasteurized milk samples passed the egg inoculation test, a gold standard for determining the presence of an infectious virus. The process entails inoculating fertilized chicken eggs with milk samples containing viral RNA and seeing whether there’s replication. Because there were no signs that the virus multiplied, the results “reaffirm our assessment that the commercial milk supply is safe,” the FDA says in an April 26 update. In an April 24 FAQ, the USDA says the meat supply is also safe but notes that proper handling and cooking of raw meat are still important.

Could the virus evolve to become more infectious for humans?

Michael Worobey, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Arizona, and colleagues have been analyzing H5N1 genetic sequences from the current outbreak. Their work suggests that the virus may have been circulating in cows since late 2023. The same set of mutations in these genetic sequences indicate to the team that a single spillover event may have allowed the virus to jump from birds to cattle, causing the outbreak. These mutations have also appeared in the genetic sequences of cats, chickens, blackbirds, and grackles on farms with H5N1 outbreaks, suggesting that the virus may have spread from infected cows back to birds and other animals.

In contrast, the genetic sequence of the virus from the infected Texas farmworker looks somewhat different. Experts suspect that the individual may have been infected by an H5N1-positive cow carrying a version of the virus not represented in recent testing.

As more cows are screened for H5N1, scientists will be able to better track if and how the virus is evolving as it spreads. But in the FAQ, USDA officials say they “have not found changes to the virus that would make it more transmissible to humans and between people.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter