Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Support nonprofit science journalism

C&EN has made this story and all of its coverage of the coronavirus epidemic freely available during the outbreak to keep the public informed. To support us:

Donate Join Subscribe

Infectious disease

Covid-19

Surface swabbing helps researchers get a handle on COVID-19 cases

Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 on high-contact surfaces could enable community surveillance to preempt outbreaks

by Mark Peplow, special to C&EN

January 19, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 3

As people infected with SARS-CoV-2 travel around a city, they can leave a bread-crumb trail of the virus on the surfaces they touch—particularly on high-contact points such as door handles.

Researchers have now shown that while the risk of picking up a SARS-CoV-2 infection from an individual contact point is very low, repeatedly testing such surfaces could provide an early warning of impending outbreaks (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00875).

SARS-CoV-2 mostly spreads through droplets and aerosols ejected when people cough, sneeze, or speak. Laboratory experiments show that SARS-CoV-2 can linger on surfaces for up to 28 days (Virol. J. 2020, DOI: 10.1186/s12985-020-01418-7), ready to be picked up by unwary fingers and transferred to a new host’s mouth or nose. But there is relatively little data on the risk of surface transmission in public places.

Environmental health researcher Amy J. Pickering of Tufts University and colleagues collected weekly swab samples from 33 different high-touch surfaces at 12 locations around Somerville, Massachusetts, a city of 81,500 people, between April and June 2020. Sampling points included crosswalk buttons, garbage can handles, and ATM keypads. The researchers also watched each location for 30 min before swabbing to record the number of touches in that period and whether those who touched the surfaces were wearing masks, gloves, or other protective equipment.

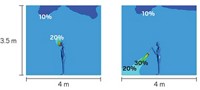

Back in the lab, they measured the amount of viral RNA at each spot using a method known as quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. From week to week, the percentage of positive samples ranged from about 3–16%, and in total 8.3% of all the swab samples tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Viral RNA was found at 10 of the locations, with the highest concentrations on a garbage can and a liquor store door handle. “We were actually quite surprised to find RNA on so many surfaces,” Pickering says. By combining these data with prior laboratory results on touch-based transmission of viruses, the team calculated that the risk of infection from a single touch of the most contaminated surface in their survey was just 4 in 10,000.

The researchers then used public health records to track the rise and fall of COVID-19 cases in the city over the same time period. They found that levels of viral RNA on high-touch surfaces offered a reasonable prediction of case trends in the community 7 days later, potentially providing a useful surveillance tool that could help public health authorities to anticipate outbreaks and take action to stop them.

“This idea of using environmental surveillance reminds me a lot of what’s been done for polio and other pathogens,” says Alicia N. M. Kraay, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Emory University, who has studied SARS-CoV-2 surface transmission. “I think it’s good research.”

Wastewater monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 is already being explored as a city-wide surveillance method, but Pickering says that surface monitoring could be applied at specific venues like schools and bars, allowing places to be quarantined before regular visitors have the chance to spread COVID-19. Surface swabs also require less processing than wastewater samples. And since people shed the virus from their respiratory tract 1–2 weeks before it appears in their feces, “surface sampling has the potential to be a better early-warning tool than sewage surveillance,” Pickering says.

Pickering is now seeking funding to test her surface surveillance strategy in schools. “Some schools are trying to do human-based testing, but there are huge delays in getting results back, so I think it could be more efficient to implement surface monitoring to detect outbreaks early,” she says.

Whatever route the virus takes from one person to another, Pickering and Kraay agree that basic public health measures offer the most effective way to reduce transmission. Along with hand-washing and social distancing, “the single most important thing we can do is wear a mask,” Kraay says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter