Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Microbiome

Bacteria find a niche in your nose

A diverse nose microbiome could protect against chronic sinusitis

by Laura Howes

May 30, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 21

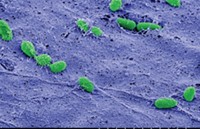

Distinct communities of bacteria living in and on many parts of our bodies play a role in human health, but what about noses? Bioengineer Sarah Lebeer of the University of Antwerp became interested in the question when her mother underwent surgery to relieve lifelong problems with chronic rhinosinusitis, inflammation of the membranes that line the sinuses that can cause headaches, a stuffy nose, and other symptoms. Lebeer has previous experience studying gut and vaginal probiotics but realized no one really knew about the nose. Lebeer’s team compared the nose-dwelling bacteria of 100 healthy individuals and 225 people with chronic rhinosinusitis and found that healthy people had up to 10 times as many Lactobacilli in some parts of the nose compared with the rhinosinusitis patients (Cell Rep. 2020, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107674). Lactobacilli are well-known beneficial bacteria, but they generally don’t like high levels of oxygen. The researchers took a closer look and discovered a specific strain they say is well adapted to survive in the nose. The bug has genes to cope with higher oxidative stress levels and bristles with flexible, hairlike tubes called fimbriae, which allow it to stick to cells in the nose. The team also made a nasal spray containing this bacterium and showed they could deliver it to patients. Lebeer says the team is continuing to study how nose Lactobacilli interact with the immune system and how this interaction might reduce inflammation.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter