Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Toxicology

Newscripts

A book about poisoning, and poisoned paperbacks

by Andrea Widener

September 24, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 38

Tales of poison and preservatives

Back before consumer safety laws, the food industry was trying out all sorts of chemicals as food preservatives. Formaldehyde in milk was common, for example, as was borax and salicylic acid on meat. “We were throwing these things into food [and] we had no idea what they were or how they affected people,” says science journalist Deborah Blum.

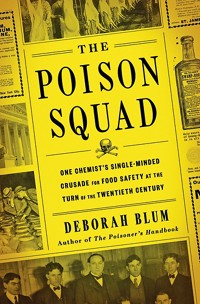

Chemist Harvey Washington Wiley was a crusader for changing that, and Blum details his fascinating story in her new book, “The Poison Squad.”

Many of Wiley’s scientific methods seem suspect today, and Blum goes into those experiments at length. But his research and persistence were one of the prime factors that resulted in the first food safety law in the U.S., the Pure Food & Drug Act of 1906.

“It’s the story of this forgotten and highly influential chemist,” Blum says in an interview with C&EN (listen to our podcast at cenm.ag/poisonsquad). “But it’s also the story of the shaping of American consumer protection and consumer food policies.”

In 1883, Wiley became chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Chemistry, the forerunner to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration. And he quickly set about detailing the “horrible quality” of U.S. food, including how questionable preservatives were affecting people.

Blum, who is a member of C&EN’s advisory board, was first drawn to Wiley because of the “poison squad” experiments, she says. Wiley recruited young government colleagues and offered them three free, healthy meals a day—plus a capsule full of preservatives. “He’s really waiting for them to get sick from these experiments, which, in fact, they did,” she says.

“From our perspective in the 20th century, the poison squad experiments seem so entirely insane that [they] really intrigued me,” she says.

Blum expected to find that Wiley was a bit crazy, but instead he turned out to be a “very good, meticulous scientist,” she says. He didn’t stop with the science, though. Wiley kept pushing against industrial and political forces that were aligned against any regulation, which reminds Blum of the political atmosphere today.

“He’s a little bit less ‘Just the facts, ma’am’ and a little bit more ‘Let’s take those facts and let’s really get people stirred up about them,’ ” she says.

So let’s thank Wiley for the fact that formaldehyde isn’t in our milk, brick powder in our paprika, bugs in our brown sugar, or sawdust in our coffee. And trust me, don’t even ask what was in the ketchup.

Books with a poisonous punch

While Blum’s book might make you feel queasy, several books at the University of Southern Denmark can actually poison you.

That’s what Kaare Lund Rasmussen found when he examined several historical texts that his librarian colleague Jakob Povl Holck brought to his imaging lab.

The pair had collaborated before on projects to look for hidden texts in the binding of books from the 1500s and 1600s, says Rasmussen, a professor of physics, chemistry, and pharmacy. These particular books were covered in green paint, but at first Rasmussen was more focused on what might be underneath.

“Immediately when I put the focused X-ray beam on the books I saw a giant peak of arsenic,” he tells Newscripts. “I connected the color with Paris green. It was one of those moments of great scientific joy.”

Developed in 1814, Paris green—copper acetoarsenite—was widely used in the 1800s for its bright emerald-green color, especially in decorations and clothing. But its arsenic base would cause sores, illnesses, and even deaths. In later years, when its toxicity was better understood, Paris green was also used as a pesticide.

Advertisement

Rasmussen isn’t sure why poison was applied to these books. “It is possible that it was applied by a bookbinder who simply liked the color green,” he says. “But of course it would act as a very effective pesticide.”

Andrea Widener wrote this week’s column, with reporting by Lisa Jarvis. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter