Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Cancer risk studies raise questions about the safety of long-lasting hair dyes

Long-lasting hair dyes are popular, and their safety has been well researched. But new epidemiology studies show their use correlates with increased risk of breast cancer

by Melody M. Bomgardner

May 3, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 17

Credit: iStock | Shoppers choose hair color not just for the shade but also for how long the color will last.

After weeks of staying at home to protect themselves and others during the novel coronavirus pandemic, many regular hair salon goers are dreading yet another videoconference call. A quick trim can help tame shaggy bangs, but what to do about those gray roots?

In brief

Most women in developed countries color their hair. Now, after weeks of isolation to tamp down the coronavirus pandemic, those locks may not be looking their best. While many consumers mull the options for at-home treatments, new data from epidemiology studies are raising questions about whether some hair color chemistries may increase the risk of breast cancer. The new studies contrast with decades of toxicology research showing the safety of reactive dye processes used to permanently color hair in salons and at home. Join C&EN to learn how hair color products work and why some experts think they deserve a closer look.

For those whose preferred hair color does not come from Mother Nature, some kind of synthetic solution is in order, and if the salons are closed, a boxed dye from the drugstore may be the next best thing.

The most high-performance products are permanent colors, which rely on reactive dyes. They last for several weeks, or until new growth requires reapplication. And permanent color is the only option for those who want to lighten dark hair by a few shades or color gray hair, says Oregon hair stylist Caryn Pozorski.

“If a client is sure what color they want, I go to permanent color as the first choice. Usually I don’t even think about it,” Pozorski says.

In skilled hands, permanent hair color provides consistent and pleasing results, which is why it is the most popular option, both in salons and at home. However, the process relies on harsh alkaline chemistry that damages hair. And hair color ingredients can cause skin sensitization and even severe allergic reactions in some users.

Pozorski’s clients ask a lot of questions about hair color. One question that stylists rarely get is whether coloring hair comes with any long-term health risks—but that may change. Two recent studies by epidemiologists who looked at data gathered from large cohorts of women found that the use of hair color products correlates with an increased risk of developing breast cancer, particularly in black women.

The results arrive at a time when the safety of cosmetic ingredients is under increased scrutiny. Consumer- and health-activist groups are pressing for legislation that tightens safety standards for ingredients and even bans on certain chemicals.

Companies that make permanent hair dyes, both for salon and for home use, have been quiet about the new studies. And even the scientists involved acknowledge that more research will be needed to determine whether the observed increase in breast cancer incidence is caused by exposure to hair color products or other factors. For the time being, the hair color market is likely to stay strong. “Clients come in, and they just want to look good,” Pozorski says.

Hair color chemistry and safety research

Hair color chemistry has changed little since 1907, when Eugène Schueller, the founder of L’Oréal, made the first synthetic hair dye by taking advantage of the color-creating oxidation of p-phenylenediamine (PPD), a coal tar dye.

One benefit of the endurance of such old chemistry is that researchers and toxicologists have had many decades to study the health effects of hair color constituents and formulations.

The beauty industry learned early on that PPD and derivatives such as p-toluenediamine can cause contact allergic reactions, which is why oxidative hair dyes bear warnings telling consumers to do a skin-patch test before using the product and to not apply it on eyelashes or eyebrows. It’s also why salon workers and home users wear gloves during application.

Wide-ranging toxicology studies, including for carcinogenicity and genotoxicity, started to proliferate in the 1970s but have not turned up consistent evidence of harm. PPD and other aromatic amines have gotten a close look because some aromatic amines have been shown to cause cancer. Regulations on cosmetics ban the use of ingredients that show a confirmed or presumed genotoxic or carcinogenic risk.

Another reason hair color is so widely tested is its popularity. As many as 80% of women in Europe, the US, and Japan have used hair dye, according to the World Health Organization. And the use of hair dye by men, particularly men over 50, is rising. Yet most of that dye seems to stay on our heads. Studies show exposure to hair color chemicals through the scalp is low, about 1% of applied mixtures. Moreover, some popular effects, such as highlights and lowlights, are applied away from the scalp.

Permanent hair color comes in two parts. One contains dye precursors and an alkalizing agent; the other is an oxidizer, usually hydrogen peroxide. After these parts are combined, the mixture—still colorless—is applied to hair for 30–45 min. During that time, a number of chemical reactions take place to create color molecules and get them inside the cortex of the hair.

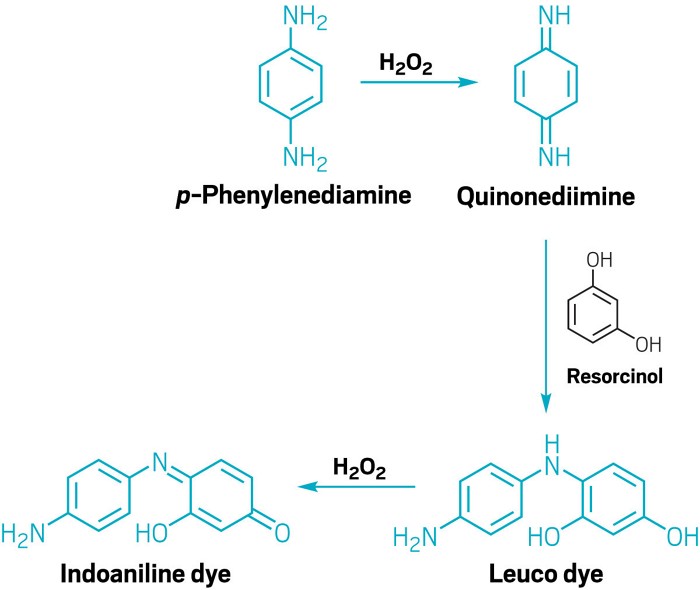

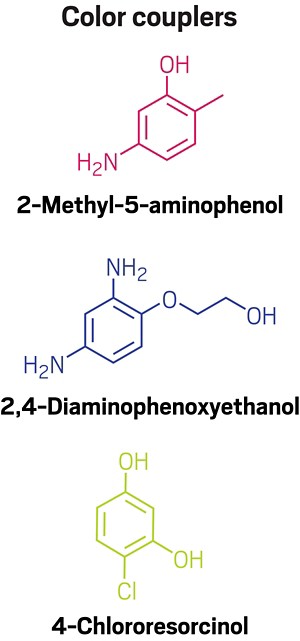

The primary dye precursor—PPD or a related aromatic amine—is oxidized by hydrogen peroxide to form a a reactive intermediate. The final dye is created by further reaction with a coupler, such as resorcinol. Typically, multiple reactions involving a color wheel’s worth of couplers are required to create the desired shade of hair.

The alkaline ingredient, usually ammonia or monoethanolamine, gets the color into the hair by swelling the outer hair layer, or cuticle. Openings in the cuticle allow the dye molecules and hydrogen peroxide to enter the hair’s middle layer, or cortex. Once in the cortex, hydrogen peroxide plays its second role: oxidizing melanin, the hair’s natural color molecule, to render it colorless. The bulky dye molecules stay wedged in to provide lasting color.

By contrast, most semipermanent hair colors are based on nonreactive dyes delivered in one bottle. They generally last for around 6 washes before fading and don’t lighten hair color or cover up gray. The newer vivid blue, pink, or purple hues also come from nonreactive dyes, sometimes called direct dyes. These molecules coat the hair shaft and generally don’t penetrate into the cuticle.

While the basics of hair color chemistry haven’t changed since Schueller’s day, styles and consumer preferences are constantly evolving. New formulations are always in demand.

“What people are looking for these days is to use hair color to express themselves,” says Valerie George, a hair color chemist and vice president of R&D for John Paul Mitchell Systems, a maker of hair products for salons. “More clients want unusual colors like rose, gold, or purple—and those have become more acceptable. Kids are doing it, and people in the workplace are doing it.”

Creating a new hair color product requires an uncommon skill set, George says. Though she’s a chemist, she had to learn about hair color on the job. “Even cosmetic chemists don’t know what is in hair color. You have to learn it from someone. I apprenticed with someone who mentored me.”

The search for new colors keeps hair color chemists busy. But George is also working to make reactive hair dye chemistry easier for salon professionals and their guests. “We’re working to create new shades that people can use with as little damage to the hair as possible,” she says. Hair colorists are also looking for products that work more quickly and are cheaper.

“These are reactive chemicals—people can be sensitized to them, and so safety is first and foremost when formulating, because I’m exposed, and my coworkers and guests are too,” George says. “My mantra always is ‘Never use any more than you absolutely have to.’ ”

George says her company’s formulas are vetted by toxicologists and go through extensive regulatory review. Major brands follow European Union restrictions specific to hair color ingredients. The EU limits the amount of certain chemicals, such as the dye precursor hydroxyethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate, and doesn’t allow chemicals that don’t have sufficient safety data, including for long-term health effects like cancer.

“Hair dyes are probably the most thoroughly studied group of personal care products,” George says.

Colorful reaction

New epidemiology studies

It was not the usual toxicology results but rather findings from two epidemiology studies that have renewed scrutiny of the chemicals in hair color and their potential link to cancer. A December 2019 study by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences found a correlation between the use of permanent hair dye and increased risk of breast cancer (Int. J. Cancer 2019, DOI: 10.1002/ijc.32738).

The study looked at data gathered as part of a larger NIEHS initiative called the Sister Study. The initiative surveyed a large cohort of US women who had a sister with breast cancer but who were breast cancer–free themselves. The goal of the Sister Study is to identify risk factors, particularly gene-environment interactions, that may help identify ways to prevent breast cancer.

The study obtained data about women’s exposure to chemicals at home and in the workplace, including the use of personal care products. On average, women with a sister with breast cancer have twice the risk of developing breast cancer as other women.

The hair product study included over 46,000 women aged 35–74 who enrolled in the Sister Study between 2003 and 2009. NIEHS researchers examined survey data about the study participants’ use of hair dyes and straighteners in the previous 12 months. Researchers followed up with the women for over 8 years to identify those who developed breast cancer.

The study showed permanent dye use was associated with a 45% higher risk of breast cancer for black women and a 7% higher risk for white women compared with study participants who did not color their hair. “These results suggest that chemicals in hair products may play a role in breast carcinogenesis,” the authors write.

The results did not surprise Adana Llanos, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Rutgers School of Public Health. In 2017, Llanos published a study based on data from women living in New York and New Jersey who participated in the Women’s Circle of Health Study, which captured data on over 4,000 women, roughly half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer. In contrast to the Sister Study participants, the Women’s Circle population included a large proportion of black women.

Llanos looked at data on the use of hair colors and straighteners by Women’s Circle of Health participants. She found that black women who used dark hair dye had a 51% increase in overall breast cancer risk and a 72% increased risk of estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer compared with black women in the study who did not color their hair (Carcinogenesis 2017, DOI: 10.1093/carcin/bgx060). These risks were higher for women who used dye more frequently. Women who had salon-applied dyes had a lower risk of breast cancer than those who applied dyes at home.

Both studies also asked about the use of hair relaxers and other straightener products, which alter the texture of hair. Relaxers contain ingredients such as lye, or sodium hydroxide, and proteins extracted from placentas. A popular hair-straightening product called Brazilian Blowout adds keratin protein to hair as well as formaldehyde.

The studies show that while 80% of African American women straighten their hair, only 3–5% of non-Hispanic white women do. The NIEHS study found at-home use of straighteners by all women is associated with an 18% increased risk of breast cancer. Llanos found that the use of relaxers by white women, but not by black women, correlated with increased risk of breast cancer.

Earlier studies had found only weak correlations between hair dye use and incidence of breast cancer, Llanos says. “But the reason I pursued this question is because there was virtually no data on this question among black women. Black women have a worse breast cancer burden in terms of mortality, so it is important to understand all the things that could contribute to this.”

Both cohort studies were hampered by the fact that the actual hair products used by the women, and their formulas, are unknown. Hair color products marketed to black women may include different ingredients or different amounts of ingredients than those marketed to white women, though the basic dye chemistry is the same.

For example, products used by black women that yield darker hair shades likely contain higher amounts of PPD. And products marketed to black women may contain higher levels of endocrine-disrupting chemicals such as parabens, fragrance, nonylphenol ethoxylates, and diethyl phthalate, according to a study from researchers at the environmental health group Silent Spring Institute (Environ. Res. 2018, DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.030).

Advertisement

On average, black women use hair dye less frequently than white women, surveys show. But they use higher amounts of personal care products generally, which can add up to more chemical exposure during a lifetime.

“In my search of the literature I’m finding evidence that black women, even adolescent girls and young women, tend to use many more personal care products and have a higher burden of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, possibly from the use of those products,” Llanos says. “It’s an important area to study in epidemiology.”

Neither the Women’s Circle of Health or Sister Study data say that using hair dyes causes breast cancer, Llanos points out. “What we’ve done is observe a statistically significant correlation on an observed relationship.” To show causation would require more research, she says.

Activists concerned about lifetime health effects from personal care products are advocating for more research and better testing for cancer end points. Sharima Rasanayagam, director of science at Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, would like to see epidemiology studies with large numbers of women of different races, including women with different breast cancer subtypes, such as ER+, ER–, and so-called triple-negative cancers. She’d also like the studies to track the specific hair products used by participants.

Rasanayagam acknowledges that toxicologists have performed hundreds of in vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies of hair color formulations and their ingredients (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.11.003). But she says those older studies may not turn up potential breast carcinogenesis.

“It is a real issue whether toxicology studies have been looking for the right end points to be relevant to breast cancer in humans,” Rasanayagam says. Animal studies use male mice and rats to avoid variables from female hormone cycles. And traditionally, carcinogenesis studies examine liver tissues rather than mammary glands for evidence of tumors.

Rasanayagam points out that environmental exposures important to breast cancer can happen very early in life. “We need to test exposures in the mother, in the womb, in gestation, in puberty, and during pregnancy—all times when mammary cells are developing rapidly.”

Breast Cancer Prevention Partners is advocating for national cosmetic safety reform and is backing a bill introduced by Representative Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) called the Safe Cosmetics and Personal Care Products Act of 2019. The proposed legislation would require the US Food and Drug Administration to oversee and review safety testing of cosmetic ingredients rather than allow industry to self-certify them.

The bill would ban the use of over a dozen cosmetic ingredients, including PPD, other coal tar dyes, and toluene, an ingredient in some common hair dyes. It also would ban formaldehyde and lead acetate, an ingredient in the men’s hair color product Grecian Formula.

Another organization pressing the beauty industry to improve the safety of its products is EDF + Business, an arm of the Environmental Defense Fund that partners with companies. Boma Brown-West, senior manager for consumer health at the EDF, works with product manufacturers, retailers, and chemical suppliers to achieve what she calls “a toxic-free marketplace without chemicals of concern in products.”

Brown-West would like to see beauty industry brands proactively formulate products without chemicals of concern, even in the absence of new regulations. “Hair products like colorants and relaxers are absolutely a hot spot for needed attention and improvement,” Brown-West says.

A team at Northwestern University used polydopamine, a synthetic melanin, to permanently dye blond hair.

Alternatives to reactive dyes

There is little evidence that cosmetics companies are developing alternatives to hair color products containing reactive hair dyes. The three main companies that own mainstream salon and consumer brands—Coty, L’Oréal, and Sally Beauty Holdings—did not respond to repeated requests for interviews about product innovation. Likewise, the Personal Care Products Council, a trade group that oversees the industry’s safety testing of ingredients, did not respond to requests for comment.

However, academic teams are experimenting with new color materials to dye hair and are reporting some promising results. In one effort, Nathan Gianneschi, a chemistry professor at Northwestern University, and postdoctoral researcher Claudia Battistella used polydopamine hydrochloride to dye blond and gray hair under conditions similar to those used in a salon or at home (ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00068).

Polydopamine is made via oxidation of dopamine. When further oxidized, it forms nanosized particles that are chemically similar to the natural melanin in human hair. Earlier efforts to use synthetic melanin for lasting hair color relied on a time-intensive dyeing method that included harsh oxidative conditions and the use of copper or iron compounds.

The Northwestern researchers used heat rather than copper compounds to catalyze the oxidation of polydopamine, speeding up the reaction in the process. They found the color particles stayed on hair without the use of a layer of iron compounds. How it works isn’t clear yet, but Gianneschi says the color longevity is likely due to electrostatic and polar surface interactions.

“We get a permanent hair color effect because of covalent interaction. We didn’t have to break the hair open. It’s potentially a more mild approach,” Gianneschi says.

The technique uses just enough alkalizing solution to kick-start polydopamine oxidation and create a dark brown or black color. A small amount of hydrogen peroxide is used to lighten the particles to achieve a range of natural-looking colors, including red or blond.

“The main goal is to use the least amount of chemicals and have a range of colors,” Battistella says. She says her team’s process is a better route to new products than earlier polydopamine methods because it harnesses the same alkalizing and oxidizing chemicals used in current hair dyes.

Another group at Northwestern developed a recipe containing the ultrathin carbon material graphene and the biomaterial chitosan to make a durable coating of dark color for hair. Other researchers have taken a more colorful approach, using chemistry from plants, such as anthocyanins derived from black currants.

For now, reactive dye chemistry will continue to be the most common choice for consumers. “I don’t think permanent hair color will go away, because people want it to work and to look good,” George says. “People trust that products are safe, and that’s the responsibility of the brand.”

But there is a subset of consumers concerned about potential risk who are thinking about their options, Llanos says. That group includes women who have been diagnosed with cancer or autoimmune diseases and are on the lookout for more benign hair color products. “As scientists, I think we need to provide information to help consumers potentially make better choices for themselves,” she says.

The next trend in hair color could come from a new take on color chemistry, Llanos says. “A segment of the population will pay more for products thought to be less harmful—and that includes me.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter