Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Diversity

The struggle to keep women in academia

Incremental gains in the number of women in chemistry faculty can’t outpace the growing number who choose other careers

by Linda Wang , Andrea Widener

May 12, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 19

When Rachel Dorin started graduate school in materials science and engineering at Cornell University, she fully intended to become a professor. “That was my goal when I got there,” she says.

But Dorin’s career ambitions changed shortly after she started her program. Despite her adviser’s telling her that she’d make a great professor and encouraging her to pursue an academic career, Dorin wasn’t sure it was the life for her. “After the first year I realized that maybe I didn’t want to be a professor,” Dorin says. “I was concerned I might be limited in terms of location; there are only a few options, and you get pretty locked down to a school.”

Dorin instead discovered that she enjoyed the business aspect of science, and in addition to earning her PhD in materials science and engineering, she minored in business. Today, Dorin is cofounder and CEO of TeraPore Technologies, which she launched after graduating in 2013 to manufacture high-performance filters for biopharmaceutical separations. “I love it,” she says. “I get so much energy from being able to work on this technology with a bright and enthusiastic team of people.”

Dorin’s decision to pursue a career outside academia is not uncommon among chemists in training. In fact, many new graduates in chemistry go into industry or pursue a career away from the lab bench.

But a disproportionate number of women choose a nonacademic career. The problem with that, experts say, is that there aren’t enough women serving as role models for the next generation of female faculty.

“If young women and minority students don’t see women and minority faculty, they might be discouraged from going that way. It’s kind of a vicious cycle,” says Mary Jo Ondrechen, a chemistry professor at Northeastern University. And “science and academia need the perspectives of women and minorities. Diverse perspectives mean better science, better education, better institutions, and better culture.”

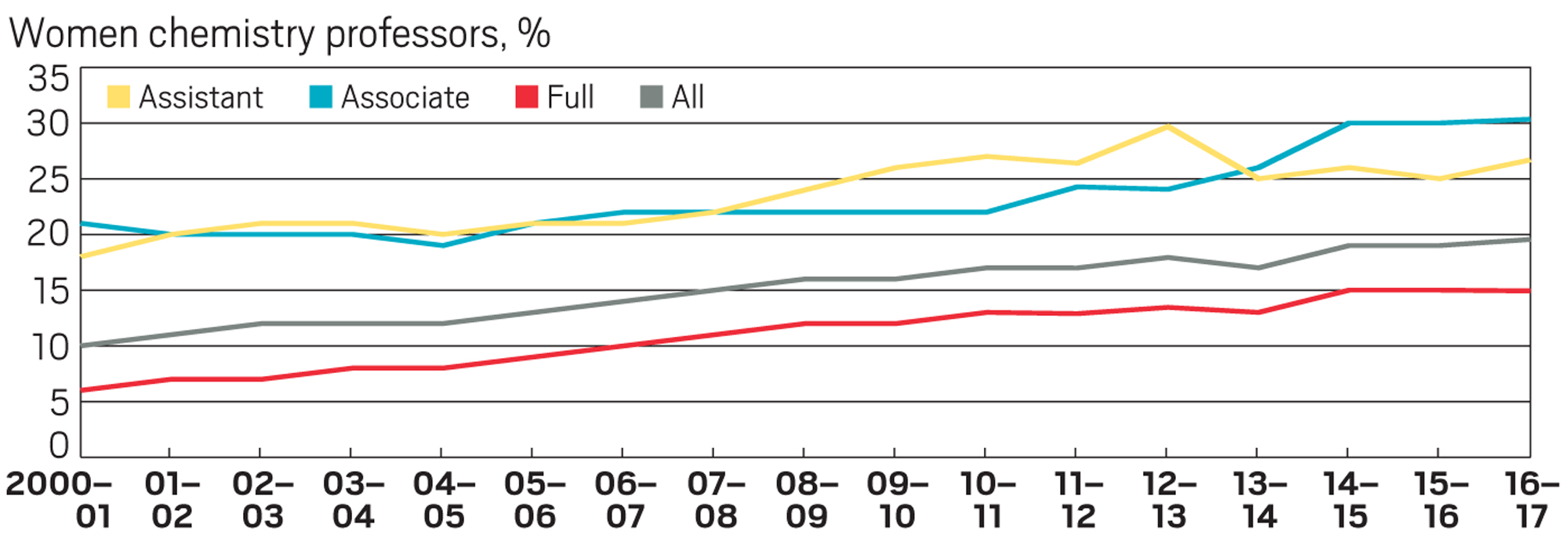

According to the latest survey conducted by the Open Chemistry Collaborative in Diversity Equity (OXIDE), an initiative funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the percentage of female faculty is creeping up slowly at the top 50 chemistry departments in the US, as ranked by federal research expenditures. In the 2016–17 academic year, an average of 20% of the roughly 1,500 chemistry faculty were women, up just 1 percentage point from the data C&EN last reported on the 2014–15 academic year. The percentage of assistant professors was up 1 percentage point to 27%, while the percentages of associate and full professors stayed flat over the same period. The overall percentage of women faculty was 16% in 2009–10, the first year OXIDE began collecting data on women faculty.

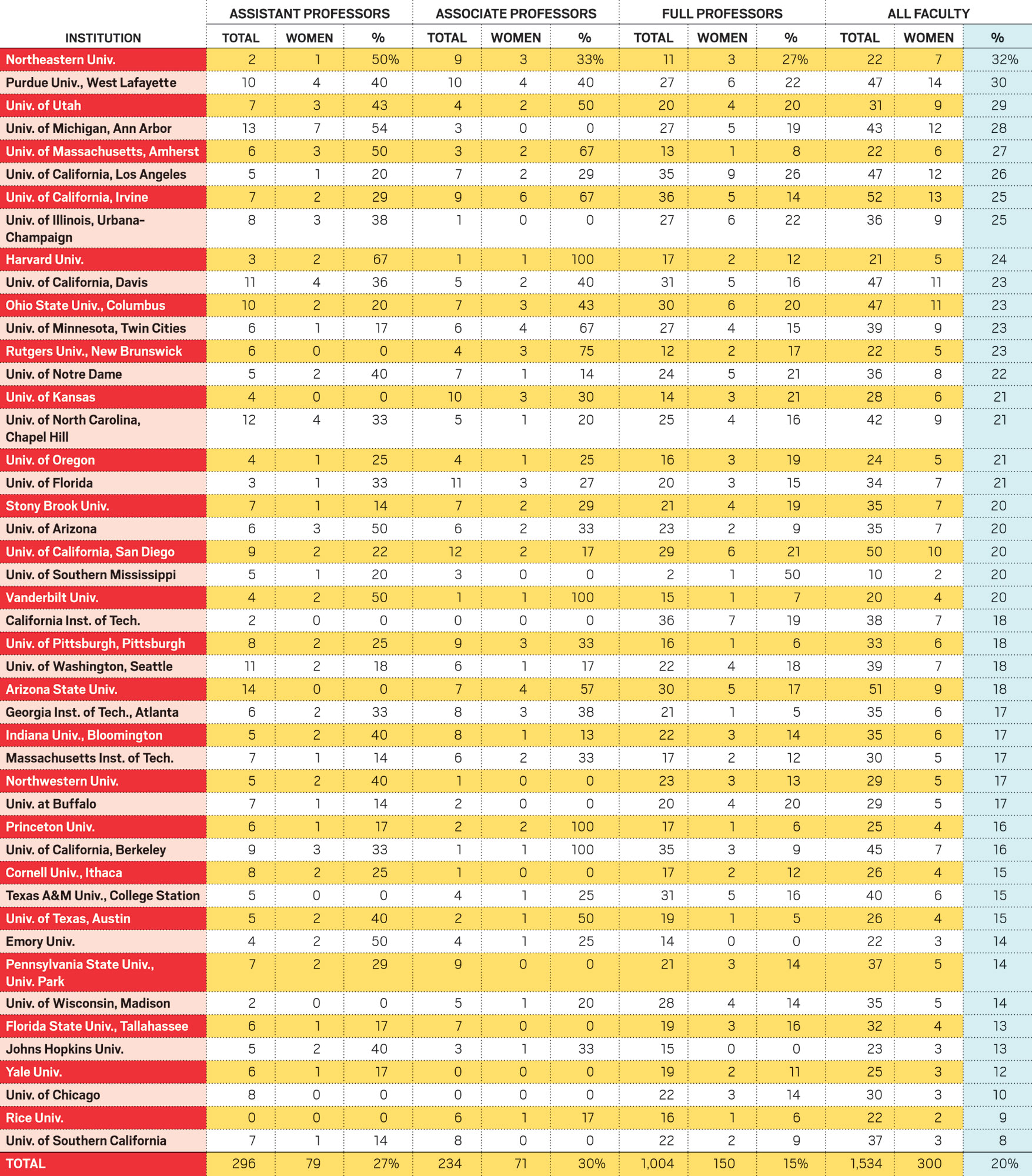

In 2016–17, Northeastern University had the highest percentage of total chemistry faculty who were women, at 32%, or 7 of 22. The University of Southern California’s was the lowest at 8%, or 3 of 37 faculty.

“The overall gender representation of women in chemistry faculties continues to move up, though slower than any of us would like,” says Rigoberto Hernandez, a chemistry professor at Johns Hopkins University and leader of the OXIDE effort. “The time constant for such increases is long because the typical residence time of a professor is well over 20 years, and hence the turnover is long.”

Notably, the proportion of women among assistant professors, 27%, is consistent with the pool of postdoctoral researchers, which was 26% in 2016, according to US National Science Foundation data, suggesting that departments aren’t discriminating in their hiring practices.

However, there is a steep drop from the percentage of female chemistry graduate students—41%—to the percentage of women postdocs. Almost 49% of chemistry undergraduates are women.

Uphill battle

Women are increasing their ranks in chemistry departments, but improvement is slow.

-

ASSISTANT

27%

Up 1 point from 2014–15

-

ASSOCIATE

30%

No increase from 2014–15

-

FULL

15%

No increase from 2014–15

-

ALL

20%

Up 1 point from 2014–15

-

Note: Tenured and tenure-track women chemistry faculty at the top schools identified by the National Science Foundation as having spent the most on chemistry research.

Lifestyle choices may explain why some women don’t pursue academic careers. “The tenure process often aligns with when people are starting families,” says Erin A. Cech, a sociologist at the University of Michigan who studies career trajectories of new parents in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. “In addition, there are often not a whole lot of support structures in place in the academy to help parents manage caregiving responsibilities.”

Like TeraPore cofounder Dorin, Lucy Sanchez entered graduate school wanting to become a professor. “What really drew me to academia was that you really are your own boss,” she says. But she experienced intense anxiety in graduate school at Indiana University Bloomington, she says. “I really lost the joy of my research at the very end. I felt like I wasn’t doing this for myself, that I was doing this for somebody else.”

Sanchez points out that of the half-dozen or so women that she knew from her graduate program, not one pursued an academic career. “We are all looking for a better work-life balance,” she says. “We’re reaching our late 20s and we really have never had a break. You either push yourself to keep climbing that mountain or you just have to stop and start your life.”

After earning her PhD in December, Sanchez found a job in industry. “Overall, it was a lifestyle choice for me,” she says.

Cynthia Burrows, chair of the Chemistry Department at the University of Utah, says that few of her students—male or female—go on to do a postdoc. “They are taking different types of jobs. I’ve had people go to law school; a lot of my students go into the biotech industry.”

Women chemists in academia, 2016–17

Note: Figures are for tenured and tenure-track women chemistry faculty at 46 of the 50 schools identified as having spent the most on chemistry research in fiscal 2014 by the National Science Foundation. When a school has multiple campuses, faculty numbers are for the campus listed. Declined to participate: Univ. of Akron; Univ. of California, San Francisco; Univ. of Colorado, Boulder; Stanford Univ.

At the same time, Burrows does see positive change in terms of increasing the number of female professors. “I was the first tenured woman in this department 24 years ago,” she says. “Now we have 10 women faculty, 7 of whom have tenure. Ten out of 32 is a decent number.”

Burrows says it’s important to make sure faculty members feel valued. “Our department’s pretty good about nominating people for awards, making sure that everyone has career potential, that they’re moving through the ranks in a reasonable way and getting the resources they need.”

Creating an environment that makes more women want to be part of the faculty will benefit everyone, says Dontarie Stallings, OXIDE research and program manager. “If we’re bringing these people to do great research, are we putting them in the best position to do great research or are we allowing the minutiae of everything else dictate their experience? The departments that are making a substantial change to their environment are the departments that are going to have long-term viability and success,” he says.

OXIDE aims to help departments identify approaches to increasing diversity and inclusion. Every 2 years, OXIDE organizes a National Diversity Equity Workshop, where chairs of chemistry departments around the US come together to discuss strategies to reduce barriers to diversity and inclusion—such as implicit bias—and increase the representation of women and underrepresented minority faculty. OXIDE began collecting annual data on women in 2009 and on underrepresented minorites in 2011. C&EN alternates the years it reports the gender and underrepresented minority survey data.

To make the academic work environment more family friendly, sociologist Cech suggests that chemistry departments look at how they’re scheduling events. “Meetings at 6:00 p.m. are really difficult for parents, and they’re quite exclusionary for that reason,” she says. In addition, when departments hold picnics or other gatherings for faculty, Cech suggests opening such events to family members. “That makes family caregiving more visible and less of something that people feel like they have to keep hidden.”

At the end of the day, it’s important to continue encouraging and enabling those women who want to go into academia, Northeastern’s Ondrechen says. “All faculty everywhere can do something by spotting students who might be good candidates in the future and asking, ‘Have you thought about a PhD? Have you thought about an academic career? Have you thought about applying for a research fellowship?’ Take students aside regardless of race or gender and encourage them.”

And if someone chooses a different career path, that’s OK, too. “If anyone shows interest in becoming a professor, I certainly encourage them,” Burrows says. “But I also think people should think hard about what their lifestyle is and what appeals to them. They see what I do and the number of times I’m here all weekend writing a proposal. And if they don’t want to do that, I’m not going to tell them that they should.”

CORRECTION

This story was updated on May 13, 2019, to fix the coloring in the chart showing percentage of women chemistry professors over time.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter