Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Undergraduate Education

Covid-19

Undergrads hit hard by pandemic navigate disruptions

Despite the hurdles, chemistry students are still determined to be scientists

by Michele Solis, special to C&EN

March 21, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 10

In spring 2020, biochemistry major Ariana Subhit was just beginning to delve into the trials and delights of advanced chemistry at Florida State University. As a second-year college student, she was taking two lab courses and researching chemical reactions that could speed the production of an insecticide. When the coronavirus pandemic closed her campus in March, these hands-on experiences came to a halt, as did in-person instruction. Her planned summer internship working at a lab at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center was also canceled. “That’s definitely going to set me back for applying to grad school,” Subhit says.

Support nonprofit science journalism

C&EN has made this story and all of its coverage of the coronavirus epidemic freely available during the outbreak to keep the public informed. To support us:

Donate Join Subscribe

For TJ Cross, the pandemic interrupted his academic timeline. In fall 2019, during his third year of college, he had transferred to the University of California, Irvine, gotten a job in the chemistry stockroom, and registered for advanced chemistry classes to fulfill the requirements for his major and to prepare for graduate school. But campus closures interrupted his momentum. “It felt like the finish line got pushed just a little bit further,” Cross says.

Even students in their last year of undergraduate school faced upended plans. With 3 years at Spelman College already under her belt, Jacquelyn Willis could have graduated early but instead stayed an extra semester to be better prepared for graduate school. The pandemic, however, kept her at home, and those courses moved online. “It was kind of like a slap in the face because the reason I stayed was to get all this experience,” Willis says.

Campus shutdowns have disrupted education at all levels. Undergraduates, many of whom are preparing to enter the workforce or continue their education in pursuit of a job, may have had reason to question their career aspirations. Learning the abstract principles of chemistry leans heavily on in-person instruction, in which questions can be answered on the spot, 3D structures can be seen with physical models, and hands-on laboratory experiments bring chemistry to life.

Despite the setbacks, many students whom C&EN and inChemistry spoke with say that the pandemic has only intensified their interest in chemistry. And they’re being supported by faculty who are redesigning programs to increase engagement and finding ways for undergrads to participate in research remotely.

Pandemic challenges

There’s no sugarcoating the fact that the pandemic created a lot of stress for students. Some felt they didn’t have the same attention span online, which meant extra work when they watched video recordings of lectures. Even charismatic teachers didn’t have the same appeal on screen. Other students found that what they learned online didn’t stick the way it did when they learned in person.

“There’s really something more focusing about having that professor in front of you and your classmates beside you,” says Seth Shaw, a chemistry major who graduated from Utica College in December 2020.

In multiple surveys taken after spring 2020, students rated finding a good study environment as a primary challenge to online learning at a variety of places, including small liberal arts colleges with many commuters, satellite campuses, and institutions serving underrepresented students (J. Chem. Educ. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00752, 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00733, and 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00774). These data from institutions in the US and Canada also showed that some students lacked access to technology or a reliable internet connection.

Students who returned home found new demands on their study time, like caring for other family members, doing household chores, or working new jobs. These new responsibilities meant getting creative about studying. Students are “sitting in their break time at work at Dunkin’ Donuts trying to solve chemistry problems,” says Shreya Bhattacharyya, a professor of chemistry and physics at Simmons University.

When some campuses opened in the fall, the experience still fell short because of campus restrictions and social distancing. “It started to feel repetitive to just get up, hop on my Zoom class, go eat lunch, come back, do homework, then go to bed. It was just me and myself and my room, and some friends that I could only see in a limited capacity,” says Spencer Clark, a sophomore chemistry and biochemistry major at Brandeis University.

Others thrived with the online schedule. That was the case with Amanda Logan, a second-year student in a chemical technology program at Delta College; the program is training her to work at nearby Dow. “I enjoy the flexibility of it,” Logan says. “I enjoy being able to watch a video and pause it, then rewind it. I’m able to learn the material more deeply than when I’m in class in person, where I’m trying to write everything down and don’t actually have time to process it until later.”

But recorded lectures don’t benefit all students. “What I’m seeing is lower-quality work” overall, says David Baker, a professor of chemistry at Delta College and one of Logan’s teachers. He says that some students seem to binge-watch his lecture videos but not absorb the lessons.

Several students reported declining grades, but professors did not see drastic failure rates; student performance often matched how they were doing before the pandemic, according to professors C&EN and inChemistry spoke with.

When students drop out, it’s not because the work is too hard but because online learning is too complicated, Baker says. Sometimes students have had to learn multiple online tools for different classes. This cognitive load may explain an odd disconnect that Anthony Fernandez, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Merrimack College, observes: some students seem completely engaged but do not complete assignments. “It shocked me,” says Fernandez, who has been teaching for 21 years.

Virtual labs

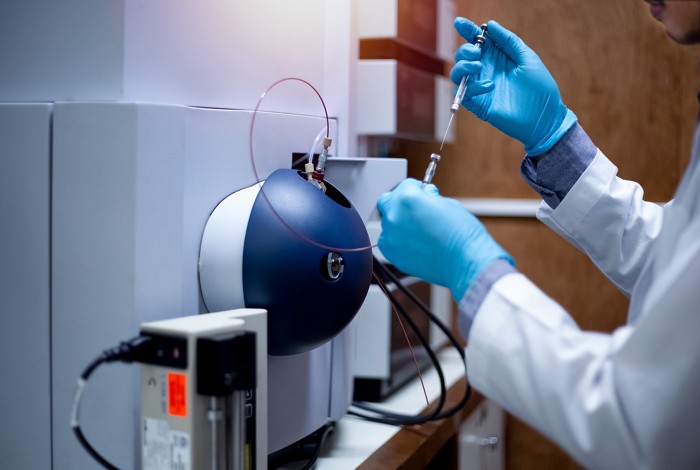

Virtual laboratory courses roughly parallel in-person courses, but seeing how something is done is not the same as knowing how to do it. Strategies for virtual labs include showing videos of experiments, having students interact with simulation programs, and providing mock data for students to analyze. Though these approaches teach data analysis and critical thinking skills, they don’t address basic skills, such as titration, pipetting, solution making, and weighing. And students aren’t getting experience with more advanced techniques such as ultraviolet visible, Fourier transform infrared, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Laboratory courses also deepen understanding of abstract concepts. For Calista Dean, a junior at Morehead State University, upcoming labs always triggered some dread. With the pandemic, however, she came to appreciate how integral labs are to her understanding the science. “I was not making the As that I usually do,” Dean says about her lab course grades. “Obviously something in the hands-on experience was invaluable to my understanding.”

Students also balked at virtual labs. “They were resistant because in their minds, labs should be a hands-on activity,” says Shanina Sanders Johnson, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Spelman College. “They also thought it was a lot more work,” given that online, students couldn’t do the multitasking that they do during in-person labs, such as calculating a dilution while a sample is drying.

Students more readily accepted kitchen chemistry. In the fall, Sanders Johnson guided her students through experiments at home, like extracting chlorophyll from spinach. Other professors assembled kits or lent students chemistry supplies to get at-home labs going.

Some institutions had in-person lab courses, but this approach required social distancing accommodations. Class sizes were halved, and students worked in their own hoods and did not share equipment.

The careful planning was worth it, says Baker, who oversaw in-person lab courses at Delta College in the fall. “People were early, they wore masks and goggles, and they were excited to be there,” he says.

Research projects outside classes also provide laboratory knowledge, but the pandemic limited these too. How this lack of hands-on experience will affect students’ chances of getting into graduate school is uncertain, though applicants from institutions that quickly reopened their labs may have an advantage if they were allowed to resume their research.

Some small undergraduate-focused institutions have not opened their labs for research yet, and faculty like Fernandez worry that this slowdown—which in his case includes languishing samples and broken equipment—will continue to have an impact after the pandemic. Pandemic-related budget cuts may eliminate money for research, for example.

Yet connecting undergraduates with research remains a priority for some, like Rama Kothapalli, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Oklahoma, who runs a program that provides research experiences for first-year students. This year she has 76 first-year students to place in labs tight on space, and she will rely on remote-friendly projects like literature searches, data analysis, and bioinformatics. “It is a lot of effort, but the rewards are equally very high,” she says.

Despite the disruptions, faculty are hoping that students can overcome any learning losses. Some professors are establishing supplementary programs for winter and summer breaks to help students review material from previous classes, with the aid of peer tutors. Others are planning to spend the first weeks of advanced courses reviewing concepts covered online in prerequisite classes. Chemistry departments are also rescheduling courses so that majors will have a chance to take the necessary laboratory courses in person. The American Chemical Society has also temporarily adjusted certification criteria for bachelor’s degree programs.

Bringing students back to campus with access to places to study will also be a good start, even if courses remain online. “I really encourage students to not give up or take their difficulties as something that’ll predict their whole career path,” Simmons University’s Bhattacharyya says. “I say, ‘Let’s try next semester on campus with a proper learning environment—that’s going to make all the difference for you.’ ”

In the meantime, some professors have embedded activities within virtual classes to help with engagement. For example, Fernandez included blank spaces in lecture notes given to students ahead of time; during his lecture, students had to fill these in, and sometimes solve problems. Though these exercises sometimes make students feel overworked or under surveillance, they helped prevent students from losing interest, says Fernandez, who recently published these methods. “Students had to produce something; they couldn’t just sit there passively,” he adds.

Finding their purpose

Once the pandemic is over, students can return to labs to bolster their skills, but correcting for a loss of interest in chemistry will be harder, says Michael Beck, a biochemistry professor at Eastern Illinois University. “Doing the hands-on stuff is the fun part,” he says. “If students don’t get that experience, they may conclude that chemistry isn’t fun.”

Fortunately, many professors are reporting the opposite. Their students are more inquisitive than ever, asking questions about microscopy and how to visualize a virus or about the chemical structure of the antiviral drug remdesivir. They are completing projects on timely topics, such as COVID-19’s deadly effects in the Black community. Some students have become the go-to people in their families for accurate information. As “somewhat trained scientists, they could help sort out the truth and get their families to practice safety precautions,” Spelman College’s Sanders Johnson says.

The pandemic also gave students new directions. Anya Gupta of Boston University was drawn to stories about vaccines and treatments, so she switched her major from public health to biochemistry. “I found myself wishing that I could be synthesizing potential treatments for this virus,” she says.

She also discovered a knack for science communication. Worried that the spring online experience had set her back, she signed on to help a professor during the summer by making prelecture videos for an introduction to organic chemistry course she had already taken. Students taking the class virtually in the fall watched these videos ahead of their lectures. “Putting together those videos helped my mastery of all the basic concepts in that course,” she says.

Advertisement

The pandemic also had one more surprise for Brandeis’s Clark: a love for organic chemistry. Thinking he may as well use his time at home in the summer to get the traditionally dreaded organic chemistry class out of the way, Clark discovered he liked the subject—so much so that he added a chemistry major to his biochemistry major.

“I discovered a passion and interest in organic chemistry as a result of a wonky online summer course,” he says. “The pandemic gave me an opportunity to explore my interest a bit more because I had a lot of time to read and think.”

As for UCI’s Cross, he did a bioinformatics research project remotely on the protease of SARS-CoV-2; this work resulted in a first-author paper in Biochemistry. And Spelman College’s Willis did two virtual internships during the summer at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and at Harvard University while living at home in Texas.

And though the pandemic may have slowed Subhit’s progress toward graduate school, it accelerated the necessary mindset. The pandemic “has made me more independent because I was very limited in who I could ask for help,” the FSU student says. “This pushed me to learn things outside of what was required of me.”

Michele Solis is a freelance writer based in Seattle covering science. This article is copublished in inChemistry magazine in partnership with ACS Education.

Correction

This story was updated on March 25, 2021, to correct the number of years Jacquelyn Willis has been at Spelman College from 4 to 3 and clarify that she could have graduated early.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter