Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

World policymakers trudge tough road as they reconvene in Ottawa for the fourth UN plastics meeting

Negotiators have had a particularly hard time with the plastics treaty. But how do UN treaties work, and how can this one move forward?

by Leigh Krietsch Boerner

April 19, 2024

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 102, Issue 12

The world is trying to figure out how to deal with the over 350 million metric tons of plastic waste we create every year. Scientists know that microplastics and chemicals from plastics are harming human health in a myriad of ways, and people in low-income communities tend to bear the burden of both the health and environmental costs. And the amount of waste continues to rise—the United Nations expects it to triple by 2050.

To address the issue, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) started working in 2022 on a global treaty to end plastic pollution. The goal is to create a legally binding agreement that addresses the impact that plastic pollution is having on human health and the environment, defines ways to reduce this impact, and resolves to initiate these measures on a global scale. On April 23, the fourth of five meetings to negotiate such a treaty starts in Ottawa, Ontario.

The full name of the effort to create a treaty—Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution, Including in the Marine Environment—is a mouthful and is usually shortened to INC. According to the original schedule laid out by the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA), the governing body of UNEP, the treaty should be finished by the end of 2024. According to diplomats, analysts, and advocacy groups, that timetable seems overly ambitious.

But what’s actually involved in creating a treaty from start to finish? A lot, it turns out. “Treaty creation is a very long process,” says Maria Ivanova, director of the school of public policy and urban affairs at Northeastern University. It can take a lot of time to draft, negotiate, and pass a treaty.

Some agreements, such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, can drag on, Ivanova says. The UN started negotiating this treaty on claims and rights in the ocean in 1973, finished the treaty creation process in 1982, and didn’t officially finalize it until 1994.

People involved in the plastics treaty hope to finish much faster than that, but there are a slew of moving parts. There are protocols to be followed, rules to be agreed on, and contentious issues to be resolved. And in the end, members hope to land on a strong and effective treaty.

TO PASS A UNEP TREATY

The United Nations plastics treaty falls under the jurisdiction of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). The UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) is the decision-making body of UNEP. These are the steps that UNEA takes to draft, negotiate, and pass a treaty. Not all treaties include all these steps, and these steps are not always followed in this order.

UNEA session

UNEA kicks off the process by setting the goal of the treaty and defining how it will meet that goal.

The assembly sets up an Intergovernmental Negotiation Committee (INC) to oversee the creation of the treaty and establish a timetable for developing it.

INC meetings

The INC holds a series of meetings to negotiate the treaty. During these meetings, the group guides the treaty member parties to:

▸ Decide on rules of procedure

▸ Define details of the problem and identify ways to address them

▸ Negotiate how to enforce the treaty

▸ Determine who will fund the treaty measures and decide how to carry the measures out

Diplomatic conference

After the member parties have agreed in INC meetings on a final text for the treaty, they hold a special conference to formally adopt the treaty.

Ratification

Within each country that is a member party, the government decides whether to approve the treaty. The approval mechanism varies by country.

Each approving country formally submits its ratification to the INC secretariat.

When 50 countries have ratified the treaty, a conference of the parties convenes.

Conference of the parties

Countries that have ratified the treaty are identified as parties and get specific voting rights. Countries that haven’t ratified the treaty can attend the conference, but they don’t have as much say in changing it.

The parties meet every year to discuss the ratified treaty and potentially to make amendments.

The anatomy of a meeting

In order to finalize a treaty by UNEA’s deadline, the INC holds a series of multiday meetings—between three and five separate gatherings for most treaties. Meetings generally start with a session called a plenary, which all participants attend. During the first plenary, the INC chair opens the session and then conducts meeting business such as electing officers and setting the meeting’s agenda and the dates, places, and agendas of any future meetings. In addition, delegates from member countries sometimes speak on their priorities for the meeting.

Another important purpose of the plenary is organizing the delegates into contact groups, smaller groups that discuss an assigned part or topic of the treaty. For example, one of the contentious issues in past plastics treaty meetings was defining the life cycle of plastic. Does it start when the fossil-fuel-based raw materials come out of the ground or when a consumer throws out or recycles a piece of plastic?

Once the INC chair sorts out the contact groups, the members break off to discuss their assigned topics. These discussions usually take the bulk of the meeting time. Near the end of the meeting, everyone comes back together for another plenary, where the heads of each contact group present their group’s recommendations for the treaty text.

Plenary attendees, including member parties, officers, and observational groups discuss these recommendations, sometimes at length, before they formally adopt potential changes to the treaty text. Once the plenary comes to agreement on the work from all the contact groups, the full group moves on to deciding on intersessional work—who will do what before the next meeting. Lastly, the INC chair adjourns the meeting.

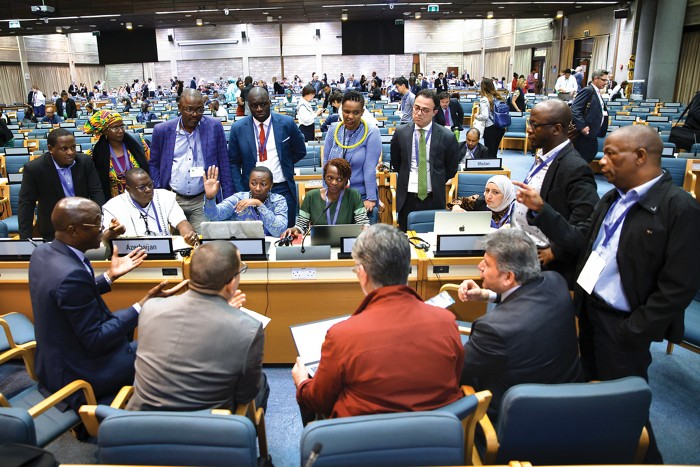

The meetings might sound relatively straightforward, but in reality they are not. Some 175 nations are negotiating the plastics treaty. At the third plastics INC meeting (INC-3) in November in Nairobi, Kenya, 1,900 delegates representing 161 countries showed up. Add to this representatives from 318 observer organizations, which include nongovernmental organizations, civil societies, and industry groups, among others. With so many people weighing in on a touchy subject like plastics, things don’t always go smoothly.

A rocky road

Compounding the challenge, the plastics treaty is operating on an abbreviated timeline, Ivanova says. UNEA created the mandate in March 2022 and proposed to have the treaty done by the end of 2024. “Two years to have a full treaty is really a feat,” she says.

The hurry is down to upcoming elections in the US and other countries. “Imagine what would happen if the administration changes,” Ivanova says. “This is why the urgency is very palpable right now.” A finished treaty, even if it’s imperfect, represents a foundation, she says. The member parties can improve it over time. Changes in government, regardless of which direction they shift, cause delays in approving international agreements.

But participants are saying that the plastics treaty is behind schedule. At INC-3, the goal was to agree on a first draft. This did not happen. Delegates spent most of the meeting in contact groups, making changes to the text of an earlier draft of the treaty known as the zero draft. But negotiations broke down in the last days of the meeting, and delegates could not agree on essential details such as what constitutes the life cycle of plastic or on whether to put a cap on plastic production.

Since a first draft was not finished at INC-3, the parties agreed that the INC chair should compile all the revisions and suggestions into a revised zero draft. But they could not agree on what intersessional work should be done ahead of INC-4, the upcoming meeting in Ottawa.

Many of the negotiators would have liked to define this between-meeting work, “but we got what we got,” says Luis Vayas Valdivieso, chair of the INC and Ecuador’s ambassador to the UK. Vayas was named chair at INC-3, replacing Gustavo Adolfo Meza-Cuadra Velásquez. “I could see in INC-3 that the delegations were ready to give a mandate for intersessional work, but maybe we just needed more time,” Vayas says.

The UNEP released the revised zero draft in late December. The formerly 31-page document had ballooned to 69 pages. Now the task at INC-4 is to get to a first draft of the treaty. Vayas says he doesn’t see INC-3 as a failure. “We had a rich and constructive discussion at INC-3, and we need to pick that up from day 1 at INC-4,” he says.

However, some experts are still antsy about the plastic treaty’s progress. “We’re about two to maybe three INCs behind. We should already have frameworks around articles of controls that we are negotiating,” says Björn Beeler, international coordinator for the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), an advocacy group. “We’re still having an argument around plastic waste, or life cycle.”

But many parties shared their positions on these matters for the first time at INC-3, says Anja Brandon, associate director of US plastics policy at the advocacy group Ocean Conservancy. These parties haven’t yet had sufficient time to discuss contrasting perspectives and opinions. The revised zero draft swelled to its current form because it reflects so many different positions on the treaty text, she says. “So the highest, most ambitious options are in there, as well as options to strike entire sections,” Brandon says.

Rules about rules

“If you locked a team of evil geniuses in a laboratory, they could not design a bureaucracy so maddeningly complex,” wrote Anthony Banbury, the UN’s former head of field operations, about the UN in a 2016 New York Times opinion piece. At such a large organization—over 125,000 people worked at the UN in 2022—rules are necessary to make things run smoothly. But these bits of bureaucracy can become monkey wrenches.

In the plastics treaty meeting, one albatross is the set of rules about how to work and make decisions. These rules of procedure are fundamental to any agreement, Ivanova says. “You need to agree on how to agree,” she says. “What are the boundaries within which you’re going to color?”

In an ideal world, parties formally adopt these rules at the first INC meeting. For the plastics treaty, this didn’t happen. Negotiators are working with the rules of procedure on a provisional basis, going back to guidelines suggested at earlier INC meetings. This means that the rules could potentially be changed at any time.

Because the rules of procedure have not formally been adopted, the threat of bringing them up hangs over INC-4. Based on the past few meetings, there’s high potential for headbutting on controversial topics, Beeler says.

Hypothetically, frustrated members stuck in a stalemate could call to finalize the rules of procedure. Early versions of these rules in the plastics treaty included the option to vote, as opposed to simply coming to consensus. But opening a vote on a detail of the treaty text is not necessarily a positive approach, because it forces parties to take a definite side, Beeler says. “You have other agreements and relationships with other countries at stake,” he says.

The former INC chair had informally agreed not to call for a vote, Beeler says. But some parties would likely choose to follow UNEP treaty precedent and finalize rules that include voting, he says. If that happened, other member states would object, and discussions of the treaty text would screech to a halt.

“I don’t want to reopen the debate on rules of procedure in INC-4, but I have to be ready to deal with any circumstances and member states who present about this matter,” Vayas says. He says he hopes the delegates can jump from the opening plenary to their contact groups and get straight to discussing the treaty text.

Moving forward

“We need to optimize our time in INC-4,” Vayas says. According to the mandate, the treaty should be finished by the end of 2024. INC-5 is scheduled to take place Nov. 25 to Dec. 1 in Busan, South Korea. “We will need an effective text, yes, but we also need one that can be implemented and signed by all the countries,” Vayas says.

Member states need to push past their disagreements and actually start negotiating, Ocean Conservancy’s Brandon says. “Do we start narrowing down all those options and aligning around how we’re moving forward, to get to something that we can actually start implementing?” she asks.

The INC-4 meeting is where the treaty text really has to be clarified, Beeler says: not only the details of the text, but what intersessional work will happen after to get to the next hurdle. “We need to further develop the content of the controls and means of implementation for INC-5,” he says. “This will be a very, very hard fight.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter