Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

CBD: Medicine from marijuana

Epidiolex earns FDA’s blessing, moving cannabidiol into the medical mainstream

by Bethany Halford

July 22, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 30

Credit: Shutterstock/C&EN

Late last month, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration approved Epidiolex, a new drug for treating rare seizure disorders. FDA approves many new drugs each year, but Epidiolex made headlines for two reasons: The strawberry-flavored syrup is designed to be palatable to young children, and its active pharmaceutical ingredient—cannabidiol—comes from marijuana.

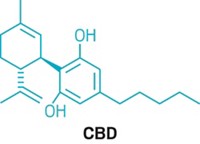

Epidiolex isn’t the first cannabinoid to be approved as a drug. Marinol (dronabinol), which is simply synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), has been used to boost the appetites of people undergoing chemotherapy since 1985. But Epidiolex is the first FDA-approved drug whose active ingredient, cannabidiol, is extracted from marijuana plants.

In brief

The therapeutic potential of cannabidiol, one of the major phytochemicals found in marijuana, was largely ignored by doctors and scientists for decades. But in recent years, its ability to treat rare seizure disorders has come to light, leading to the first FDA approval for a drug that contains cannabidiol. As scientists try to understand the mechanism of the compound and explore its possible health benefits, some worry that hype is threatening to outpace hope. Read on to learn more about this cultural phenomenon.

Cannabidiol, or CBD, has sprouted weedlike into a cultural phenomenon that’s overgrown its roots in medical marijuana. Dietary supplements containing varying amounts of CBD have been touted as remedies for insomnia, anxiety, and pain. Makers of beauty products have cottoned on to the CBD craze too, spiking mascara, lip balm, and eye cream with the cannabinoid. CBD-infused water and sodas promise relaxation along with refreshment.

Unlike THC, the compound in marijuana that gets people high, CBD isn’t psychoactive. What CBD actually does—and how it does it—is somewhat debatable. But scientists say there is hope to be sifted from all the hype. Dozens of clinical trials are taking place to determine if CBD is an effective treatment for an array of disorders while scientists try to figure out precisely how the compound works. Now that CBD has received FDA’s blessing as a legitimate drug, the work, researchers say, is just beginning.

CBD’s therapeutic beginnings

Raphael Mechoulam, an organic chemist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was among the first to explore the therapeutic potential of CBD. After determining the complete structure of the compound in 1963—several decades after it had first been isolated and studied by legendary organic chemists Roger Adams and Alexander R. Todd—Mechoulam’s interest was piqued by anecdotal reports of cannabis as a seizure remedy in historic literature. He points to a 15th-century treatise on hashish that relates the tale of a poet who gave the substance to the son, who had epilepsy, of an important official in Baghdad. The son’s seizures disappeared, but he had to take hashish for the rest of his life, according to the story.

Although anecdotal, and possibly fabricated, this story got Mechoulam thinking about CBD as a treatment for epilepsy. He set up a collaboration with a group in Brazil and started studying CBD in animal models of epilepsy with good results. Buoyed by their success, the researchers decided to conduct a small human trial.

Mechoulam isolated half a kilogram of CBD from hashish and sent it to São Paulo, Brazil, where it was used in a small study to test its effects in epilepsy. In the trial, which included 15 people with epilepsy taking antiseizure medication, eight people were given 200 to 300 mg of CBD daily for four and a half months in addition to the antiseizure medication, while seven people received a placebo. Four people in the CBD group experienced virtually no seizures during the trial, three others reported a partial improvement in their condition, and one person saw no change. The placebo group also experienced no change.

The results were published in 1980 to little notice. “I was surprised and disappointed that nothing happened,” Mechoulam says. No one expressed any interest in replicating the study or conducting a larger trial. Three decades would pass before the research was revived.

While the medical establishment failed to notice Mechoulam’s study, decades later word of the results reached parents of children with two rare forms of epilepsy—Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, which are characterized by frequent seizures that usually aren’t controlled with medication. As medical marijuana became legal in a few U.S. states, these parents, and others affected by severe forms of epilepsy, sought out dispensaries that sold cannabis that was high in CBD and low in THC to treat their children’s worsening seizures.

Sam Vogelstein didn’t have Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, but he was diagnosed with a hard-to-treat variant of epilepsy when he was four years old. By the time he was 11, in 2012, his parents had tried nearly two dozen medications to decrease the number of his seizures—five-to-20-second events where he’d partially lose consciousness, his eyes glazing over and his jaw slackening—which could happen as many as 100 times each day.

Sam’s parents, Fred Vogelstein and Evelyn Nussenbaum, had also read the literature and anecdotal reports of CBD being used to treat seizures. They tried a tincture made from purportedly high-CBD marijuana supplied by a dispensary in California, where they live. But the supply’s CBD content wasn’t reliable, so sometimes it eased Sam’s seizures and sometimes it didn’t.

That inconsistent dosage—not to mention the challenge of obtaining the product in states with differing attitudes toward products made from marijuana—set families affected by rare forms of epilepsy on a trek to legitimize the drug. Vogelstein and Nussenbaum led the way after noticing a parenthetical note in the materials and methods section of a 2010 paper in Seizure that used CBD in an animal model of epilepsy. The researchers mentioned that GW Pharmaceuticals had provided CBD for the study. The British pharmaceutical company was already marketing Sativex, a combination of equal parts CBD and THC that’s used to treat spasticity and other symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Although Sativex isn’t approved in the U.S., it was approved in the U.K. in 2010, with many other countries following suit.

Epilepsy wasn’t GW Pharmaceuticals’ focus in 2012, Nussenbaum said in April when she spoke to the FDA panel reviewing the company’s New Drug Application for a cannabidiol product. “But they had greenhouses, plant stock, labs, and they were extracting cannabidiol and other cannabis compounds regularly and systematically.” Nussenbaum told the panel that she never aspired to treat Sam with cannabis. “Honestly, if I’d found good science that a motor oil extract could help seizures, I would have pursued that, but I pursued Dr. Geoffrey Guy instead,” she said.

Nussenbaum convinced Guy, GW’s cofounder, to let Sam try GW’s purified cannabidiol, an epic process that Fred Vogelstein wrote about in Wired in 2015. In May of 2013, Sam became the first person to take the drug now known as Epidiolex.

Epidiolex made Sam’s seizures virtually disappear. For the past two years, he’s been completely seizure-free on a combination of Epidiolex and Depakote, a common add-on treatment for epilepsy. “Now I can understand what goes on at school, and I can have adventures that never would have been possible before. I just went to South Africa for two weeks without my parents on a school trip. I had a bar mitzvah 18 months ago,” he told the FDA panel in April. “I wouldn’t have been able to do any of that if I hadn’t tried this medication. It changed my life.”

Sam’s isn’t the only life Epidiolex has changed. In the past 14 months, GW Pharmaceuticals published three clinical trials of the drug, two in the New England Journal of Medicine and one in The Lancet. In the double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that enrolled more than 500 patients, a CBD oral solution, taken with other medications, halved the number of seizures in over 40% of children and young adults with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome.

The results were enough to garner FDA’s green light, offering for the first time a treatment for Dravet syndrome. But Nicole Villas, a former chemist who has a son with the disorder and serves on the Dravet Syndrome Foundation’s board of directors, notes that Epidiolex isn’t a cure. Some patients, such as her son, don’t respond to CBD. And others experience side effects, such as sleepiness, reduced appetite, diarrhea, and elevated liver enzymes, which can be a sign of liver damage.

But the fact that there is now a drug available for these children to try, Villas says, is a huge step forward. “To have something that’s well manufactured, that’s regulated, that can be given in highly consistent doses, and has an indication for Dravet syndrome is a wonderful thing,” she says.

The science of CBD’s success

CBD doesn’t work in every person with a seizure disorder, and there’s little definitive information about its mechanism of action. Scientists are now trying to unravel how it works to determine why some people benefit and others don’t and also to figure out if it might alleviate other disorders. “The literature on potential molecular targets of CBD is very large and quite conflicted,” says GW’s Head of Discovery Research Ben Whalley.

The scientific literature implicates at least 65 distinct molecular targets for CBD. Whalley says 50 of those targets can be ruled out when considering the concentrations of CBD required to engage them. For example, he says, in one study in cells, CBD was administered at a concentration that’s 500 times as great as what’s possible to physically dose a patient with. Surprisingly, scientists have also determined that CBD doesn’t bind to the active sites of the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, which is where one would expect cannabinoids to be most active.

Advertisement

When it comes to CBD’s anticonvulsant activity, Whalley says, “there isn’t any existing data to say that a particular molecular target is implicated in CBD’s effects of human epilepsies.” But animal studies have given scientists a few ideas of how the compound might be working, he says.

One plausible target is G protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55), which is expressed in the brain and peripheral organs. In the brain, it regulates synaptic transmission—the process that sends signaling molecules from one neuron to another. Connections between these brain cells are stronger when GPR55 is activated.

Seizures arise when neurons become overactive at transmitting signals, firing more frequently than they should. “CBD will actually block the GPR55 receptor,” Whalley explains, and in doing so reduce how often the neuron fires. In a rodent model of epilepsy, animals engineered without GPR55 don’t respond to CBD, whereas those with the receptor do.

Whalley also thinks that CBD might be desensitizing transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) to dampen seizures. “If you activate a TRPV1 receptor, an ion channel opens, and in the case of a brain cell, more calcium will flow into the brain cell,” he explains. “That is actually counterproductive if you’ve got a seizure because it will make the cell more excitable.” CBD seems to activate TRPV1, but it then quickly desensitizes the ion channel, effectively blocking the transport of calcium into the cell. Studies show that CBD doesn’t work well in epileptic animals engineered not to express TRPV1.

Finally, CBD is also known to engage a channel that transports adenosine—an anticonvulsant compound that the body makes. Whalley says it’s highly plausible CBD inhibits seizures via adenosine, but more experiments are needed to prove the relationship.

Whalley notes that these molecular targets aren’t specific for a particular seizure type or syndrome. So, he says, CBD could be used for other types of seizure disorders, including intractable epilepsy, but that the clinical work still needs to be done.

“The only really compelling clinical evidence to date is essentially the three clinical trials where we’ve reported results for seizure,” Whalley says.

Promising prospects

Because CBD appears to be able to engage so many targets, researchers have been exploring its use for a number of diseases. Its interaction with voltage-dependent anion channel 1 hints that it might be useful for treating movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease. And its ability to interact with serotonin receptors makes scientists think it could be useful for treating depression, anxiety, and psychosis in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. At low concentrations, CBD can bind to an allosteric site on the endocannabinoid receptor CB1 and prevent that receptor from effectively binding to THC at its active site—a mechanism that could be used to treat disorders, such as obesity, where there’s excessive activation of CB1 by cannabinoids made by our bodies.

But just because CBD interacts with those receptors doesn’t mean it elicits an effect. “What’s really needed is clinical data in patients. We need to see what’s genuine hope and what’s hype,” says Roger Pertwee, an emeritus professor at the University of Aberdeen and GW Pharmaceuticals’ director of pharmacology, who has been studying CBD and related cannabinoids for more than 45 years. “It is much more expensive and difficult and time consuming to do human studies, but at the end of the day, that’s what is needed.”

Roger McIntyre, a University of Toronto psychiatrist and pharmacologist, agrees. “Broadly, the scientific basis for cannabidiol is very strong,” he says. “Where things start getting a little thin is when it comes to rigorous, large, randomized, controlled trials, which are the gold standard in medicine.” There are currently more than 40 active clinical trials of CBD for use as a treatment for a wide range of disorders, including cocaine dependence, Parkinson’s disease, and bipolar depression.

McIntyre is particularly interested in using CBD to treat mental illness, for which existing medications often don’t help. “There’s not just an unmet need,” he says. “There’s an urgent, pressing, unmet need for something very different” from the medications currently available to treat mental illness. He points to a small trial published late last year sponsored by GW that showed 43 people with schizophrenia who took 1,000 mg of CBD daily for six weeks had fewer psychotic symptoms than those in the placebo group.

And yet, when McIntyre is asked if he’d recommend using CBD to treat mental illness, his answer is a resounding no. Before he changes his answer, he wants to see more clinical data. “What’s there for CBD looks very promising. At the same time, there have been many occasions in the past where what we thought was promising in theory didn’t quite pan out.”

“I think CBD has a lot of potential in many different areas, but I think one has to be clear about what the expectation is,” adds Melanie Kelly, a pharmacologist who studies cannabinoids at Dalhousie University and executive director of the International Cannabinoid Research Society. “The hype around it is probably pushing it to a position where we may have expectations that go beyond the evidence that we have.”

Gathering that evidence, particularly in the U.S., has been a daunting enterprise. As a compound that’s derived from marijuana, CBD is listed as a Schedule I substance. Historically, that has limited the number of researchers that have access to it, says Bryan Roth, a pharmacologist who studies cannabinoids’ mechanisms of action at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Also, Roth says, you need a separate license for each marijuana-based compound you study. For example, his lab had permission to study THC, but when they became interested in studying CBD, they had to apply for a separate license. A year passed before the Drug Enforcement Administration gave Roth the official nod. With obstacles like that, he says, “you have to be pretty motivated.”

Now that FDA has approved Epidiolex, DEA’s scheduling of CBD will have to change. “This is good news,” says D. Samba Reddy, who studies drug development for epilepsy and seizure disorders at Texas A&M University. With FDA’s blessing, Epidiolex will soon become available through medical distribution channels, he says. “It will open new frontiers for research.”

CBD supplements

Just because CBD has only recently been approved as a drug doesn’t mean that people haven’t already been consuming it other ways. High-CBD strains of cannabis and other CBD-based products are available by prescription in states where medical marijuana is legal. And dietary supplements containing small amounts of CBD derived from hemp have been available at health food stores and online for several years.

Cambridge Naturals, a health and wellness store in Cambridge, Mass., keeps its extensive array of CBD-based supplements locked in a see-through cabinet toward the back of the store. Zach Milligan-Pate, who manages supplements for the store, says that when Cambridge Naturals first started selling CBD dietary supplements and consumer products roughly two and a half years ago, they stocked six different products. Now, he says, they sell as many as 30 different items containing CBD. Offerings include liquids, capsules, and beauty products.

Initially, Milligan-Pate says, consumers were lukewarm to such products, but over the last nine months or so, demand has taken off—spread largely via word of mouth. Most people, he says, seek out CBD products to help manage stress, sleep, and pain. “CBD is having a very vivid moment right now,” he says.

CBD’s recent trendiness gives many scientists pause. “It seems to have become something that people believe is like flaxseed oil,” says Kari Franson, a psychopharmacology expert at the University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. “We need to be clearer that it’s probably not a dietary supplement but rather there is potential as a pharmaceutical. I mention this because I have walked into my Colorado dog-food store and been offered CBD dog food.”

But Stuart Tomc, vice president of human nutrition for CV Sciences, a company that sells CBD supplements, disagrees. He points out that the amount of CBD in most supplements is quite small, about 15 mg per capsule. A 30-kg child taking Epidiolex would consume as much as 600 mg of CBD per day.

“There is no comparison,” Tomc says. “FDA approved 99% pure CBD for very rare forms of epilepsy while most naturally occurring hemp extracts only contain between 10–25% CBD. Hemp extracts consist of many different naturally occurring phytonutrients and fatty acids. They are superfoods; they are not drugs.” He adds, “Our products do not treat, cure, or ameliorate diseases or disease symptoms. If you have a disease and you want to use cannabidiol, we strongly encourage you to talk to your pharmacist and physician and look for products like Epidiolex.”

But Tomc also thinks there has been some fair criticism of CBD consumer products. The industry, he says, which may include hundreds, possibly even thousands of CBD products, lacks standardization.

Nicholas Vita, CEO of the medical cannabis company Columbia Care, agrees that the CBD market is fractured. “You have some very responsible players that really go to great lengths to produce pharmaceutical-quality products, and then you have a lot of ‘mom and pop’ cottage industry players that are trying to get there but really miss the mark.”

With so many players in the CBD market, there are bound to be some bad actors. In January, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention investigated suspected cases of poisoning in 52 people in Utah who had taken supplements labeled as containing CBD. Nine of the products CDC tested as a result of the poisoning outbreak contained no CBD at all. Instead, the agency discovered the products contained 4-cyano cumyl-butinaca, a synthetic cannabinoid that’s been associated with fatalities in Europe. FDA has also cracked down on companies making claims that CBD can treat cancer.

“I do, unfortunately, see a lot of health claims being thrown out online about all the things cannabidiol might be useful for,” says Robert Laprairie, who studies cannabinoid pharmacology at the University of Saskatchewan. “We are very much in the learning and understanding phase of cannabidiol as a medicinal entity. It’s too soon to make a lot of claims.”

Dalhousie’s Kelly agrees. “We came out of this era of complete prohibition on cannabis, which was probably unwarranted, to this galloping ahead without appropriate research,” she says.

Still, now that CBD has earned the status of legitimate drug, many expect interest in the cannabinoid to grow. Doctors await the results from clinical trials to see whether CBD will find medicinal uses beyond rare seizure disorders, and scientists continue to unravel the complex mechanisms that give this cannabinoid its properties. For CBD, the long, strange trip continues.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter