Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference offers fertile ground for 2024 dealmaking

Executives are hoping to capitalize on Big Pharma’s willingness to spend

by Rowan Walrath

January 12, 2024

Protagonist Therapeutics CEO Dinesh V. Patel has been attending the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference since 1998. Twenty-six years on—save for the 3 years when the COVID-19 pandemic reduced it to a series of webinars—Patel says there’s still a prestige associated with the event.

It hasn’t been bad for his business either. After Patel’s presentation Tuesday, Protagonist’s stock price bumped up about 5% and continued to rise over the following day.

“We believe that our story is getting a lot of attention and positive reception,” Patel says. “And we are having fun. It’s all, you know, back-to-back meetings, things like that. This little hotel room . . . they are charging us $3,000 per night, but it’s all worth it.”

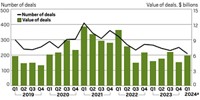

A flurry of dealmaking activity over the past 6 weeks buoyed the general mood going into this year’s conference, lovingly called JPM by the 20,000 or so biopharmaceutical professionals who flock to San Francisco each January. In December, large pharmaceutical companies announced several multibillion-dollar acquisitions: AbbVie will spend $8.7 billion on neuroscience firm Cerevel Therapeutics; Roche will spend $2.7 billion on Carmot Therapeutics, which makes weight-loss drugs; and Bristol Myers Squibb will spend $4.1 billion and $14 billion to buy RayzeBio and Karuna Therapeutics, respectively.

A few more acquisitions kicked off the conference, albeit smaller than those in the year-end rush.

Novartis announced it would acquire Calypso Biotech, a Merck & Co. spinoff developing antibodies for gastrointestinal disorders, for $250 million, and Merck & Co. revealed plans to buy peptide maker Harpoon Therapeutics for $680 million. GSK announced its plans to buy antibody maker Aiolos Bio for up to $1.4 billion, and Johnson & Johnson said it would acquire antibody-drug conjugate developer Ambrx for $2 billion—the largest pharma deal announced during the conference and the only multibillion-dollar acquisition.

Pharma is on the hunt

There’s still money to be spent. As of Dec. 10, biopharma companies were sitting on $1.37 trillion, according to EY’s annualFirepower report. When those companies approach patent cliffs, they’ll lose billions of dollars in revenue, and as Arda Ural, EY’s Americas industry markets leader for health sciences and wellness, notes they’ll have to make it up somehow.

“The need for new products—late-stage, derisked assets—is there, much more so because of the biologics losing their exclusivities in massive amounts,” says Ural, who flew from New Jersey to San Francisco for the conference. “The cumulative impact is going to be over $300 billion.”

The pending patent cliffs can drive acquisitions, but it can lead to other types of partnerships too, like Isomorphic Labs’ licensing deals with Novartis and Eli Lilly and Company, announced a day before the conference began. Japan’s Astellas Pharma is explicitly looking for such collaborations: Chinatsu Sakata-Sakurai, vice president and head of the pharma’s targeted protein degradation work, is seeking drugmakers with an “entrepreneurial spirit” to expand her company’s pipeline. Astellas, in turn, can provide functions like manufacturing, commercialization, and medical affairs, she says.

Many executives of smaller biotechs came to JPM to take advantage of that dynamic.

Nicolas Tilmans is CEO of a 4-year-old start-up called Anagenex. Backed mostly by tech-focused venture capital firms, Anagenex is behind machine learning software that takes data from DNA-encoded libraries and other sources and designs small molecules for protein targets.

Anagenex has one disclosed collaboration, with Nimbus Therapeutics. Tilmans has spent much of his time this week looking to set up similar deals.

“We’re looking to have one, possibly two additional partnerships,” Tilmans says. “We’re trying to develop [collaborations] that will carry us a little bit longer.”

Victoria Richon, CEO of another 4-year-old start-up, called Entact Bio, says she used JPM as a way to introduce Entact to Big Pharma. Launched in late 2022 after about 3 years in stealth, Entact is named for medicines it calls ENTACs—an acronym for enhancement-targeting chimeric molecules. Richon and her team have been working to identify proteins whose lack or misplacement is driving disease, then drug those using enzymes that remove or shorten chains of a small regulatory protein called ubiquitin.

“We spent a lot of time talking to different pharmas to introduce the concept,” Richon says. “One of the things that’s really important as we think about the platform that we’re building and the breadth of the opportunity is really to start thinking about partnerships.”

Tilmans and Richon are at the beginning of their start-up journeys. But JPM also hosted founders and executives who were at the close of theirs. Some 27% of biotechs do not have cash to fund operations for more than a year, according to EY’s Ural, who describes it as a “Tale of Two Cities situation.” Those executives have a very different motivation for dealmaking: without a pharma partnership, they won’t make it to next year’s JPM.

“There’s definitely still a culling of the herd, with some distressed companies that are out here trying to execute a Hail Mary or a fire sale,” says Jeffrey Quillen, a partner at law firm Foley Hoag and cochair of its life sciences industry group.

What’s next

When Ural arrived in San Francisco, he felt cautiously optimistic. December’s M&A rush made 2023 one of the best years of all time for biotech acquisitions. After spending some time in Union Square, he thinks it’ll hold up.

“I kind of dropped the ‘cautious,’ ” Ural says. “Now, I’m optimistic.”

Samir Ounzain, cofounder and CEO of a Swiss biotech called Haya Therapeutics, feels the tides turning too. Haya’s largest venture capital funding was back in 2021, when it closed on a $20 million seed round to fuel the development of antisense oligonucleotide therapies that target long noncoding RNAs. Now he’s hoping that improved sentiment about the industry will help him raise a series A.

“There’s absolutely a real rebound in interaction and interest in funds being raised,” Ounzain says. “Things seem to be warming up quite rapidly, which is welcome news for all companies like Haya.”

Richon is less sure; she thinks it won’t be until 2025 that things grow a little easier for biotech executives. Quillen says most people he’s talked to are focusing on the short term—Q1, and nothing beyond.

At Anagenex, Tilmans believes 2024 will be a “head down” year. The company was founded just 3 months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, and it’s just getting off the ground. Tilmans hopes he can seize on partnership opportunities and excitement around artificial intelligence, but there’s work to be done.

“In some ways, the environment and the optimism, or not, at JPM doesn’t matter terribly much for what we have to execute,” Tilmans says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter