Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Development

The new drugs of 2018

A peak in FDA drug approvals came as companies increase their focus on the genetic drivers of disease

by Lisa M. Jarvis

January 21, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 3

Credit: Chris Gash

In brief

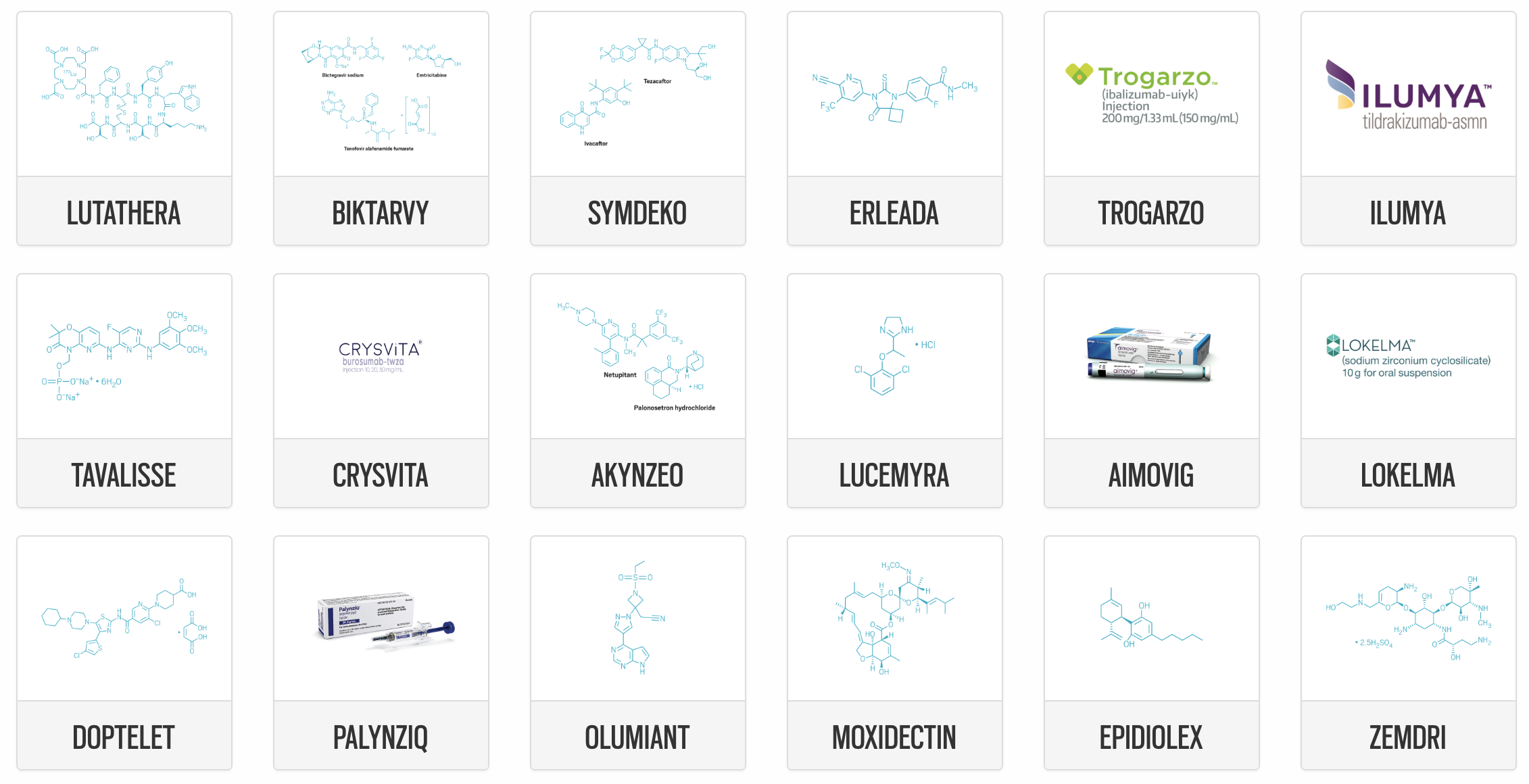

The US Food and Drug Administration approved a record number of new drugs in 2018, with 59 reaching the market. The swift pace of innovation is expected to continue as companies increasingly match their drugs to patients’ genetic profiles and the regulatory agency enhances its ability to quickly assess the safety and efficacy of molecules in the clinic. Read on for the scientific highlights and therapeutic trends reflected in 2018’s new drugs.

Pharmaceutical industry productivity was robust in 2018, a year in which the US Food and Drug Administration approved a record 59 new drugs. The new high-water mark for innovation comes as companies increasingly focus their efforts on diseases with a clear genetic driver and the regulatory environment becomes more favorable to industry.

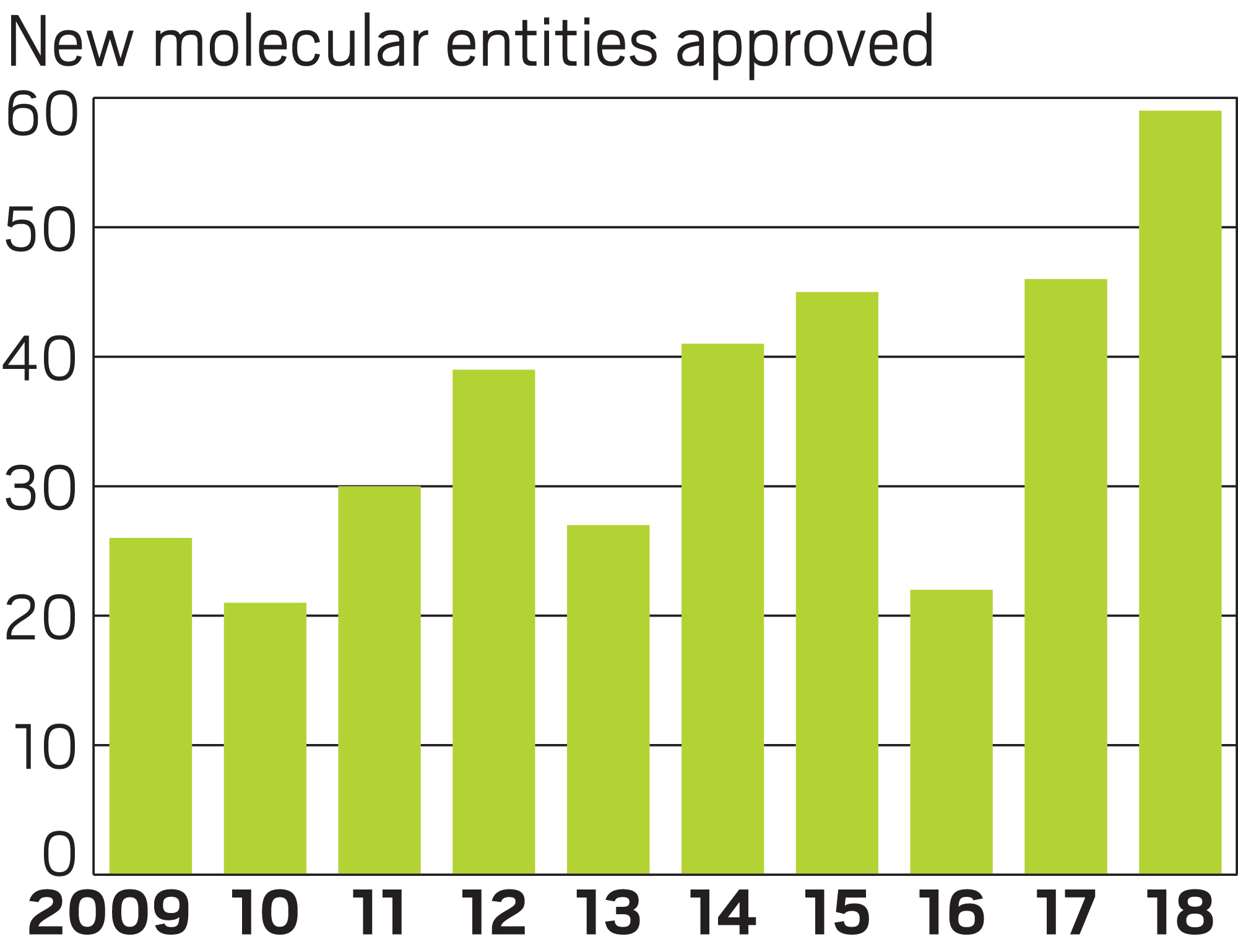

The 59 newly approved drugs are a leap from the 46 treatments approved in 2017—a year that represented a two-decade peak in productivity. According to research by J.P. Morgan, the FDA has, on average, approved 20–25 new drugs per year in the past two decades. But annual approvals in the past five years, except for a dip in 2016, have been in the range of 40–50 new drugs. The investment bank expects approvals to stay at that high level “for the foreseeable future,” driven by advances in oncology, immunology, and gene therapy.

In addition to being notable for the sheer quantity of drugs approved, last year included several important scientific achievements. Of the 59 new drugs, 19 work by a novel mechanism of action, and still others represent a new way of treating disorders that have long gone neglected. Examples include the three CGRP-targeted drugs approved for migraine prevention, the first new pill for endometriosis in more than 10 years, and the first marijuana-extracted drug, which addresses a rare form of epilepsy.

A high point was the approval of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals’ Onpattro. The drug is the first treatment to act by RNA interference, the technique of using short, double-stranded nucleotides to prevent messenger RNA from delivering the recipe for making a bad-behaving protein. It capped a 16-year journey for Alnylam, which was formed in 2002, just four years after the discovery of RNAi.

The approval was lauded as an important scientific achievement, but the potential for companies to turn a profit from new technologies like RNAi remains to be seen. Alnylam spent more than $2 billion from its inception to the drug’s approval to treat a rare disease called hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, a sum that underscores the challenge of translating promising ideas into actual products. Moreover, Onpattro addresses a small patient population and already faces competition from another treatment, the oligonucleotide-based Tegsedi from Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Akcea Therapeutics.

New drugs by the numbers

59

New molecular entities approved in 2018

46

New molecular entities approved in 2017

64%

Small molecules

20%

Antibodies

58%

Rare-disease treatments

16

New cancer treatments

14

New drugs with “breakthrough therapy” status

$450,000

Annual cost of Alnylam’s Onpattro

4

Products added to Pfizer’s pipeline

Sources: US Food and Drug Administration, Alnylam.

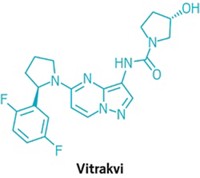

Another scientific advance was the green light for Loxo Oncology and Bayer’s TRK fusion inhibitor Vitrakvi. While previous cancer drugs got the FDA’s nod on the basis of the location of a patient’s tumor—such as the lung or breast—Vitrakvi was approved to treat anyone with tumors harboring a TRK fusion mutation. It’s the first small-molecule drug to score a “tissue agnostic” approval, and Loxo is working on several other products that treat patients according to their genetic profiles.

The promise of such targeted cancer therapies was underscored earlier this month when Eli Lilly and Company agreed to buy Loxo in a deal worth $8 billion. It was one of three recent large acquisitions by big pharma firms looking to bolster their oncology portfolios; the other two were Bristol-Myers Squibb’s $74 billion purchase of Celgene and GlaxoSmithKline’s $5.1 billion buy of Tesaro.

The acquirers’ goal is to capture a larger slice of the increasingly competitive cancer arena, which in recent years has been the source of significant innovation. In 2018, cancer therapies represented 27% of all new drug approvals, a proportion that is on par with that in 2017.

The record number of new drug approvals is “positive all around for the industry, as well as for patients,” says Karen Young, US pharmaceutical and life sciences leader at the consulting firm PwC. The high total reflects a proactive regulatory agency that continues to “focus on driving more efficiencies in their processes,” she adds.

Indeed, under the leadership of Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, the FDA has been focused on streamlining and modernizing the sometimes cumbersome process of developing a new drug.

The agency’s latest initiative was unveiled earlier this month at the annual J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference, where the government shutdown prompted Gottlieb to deliver a speech via teleconference rather than in person. Gottlieb said the FDA will establish the Office of Drug Evaluation Science, to be housed within the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research’s Office of New Drugs.

The unit, which is expected to have a staff of more than 50, is tasked with standardizing and modernizing the way the agency assesses the safety and efficacy of products. The broader goal is to lower the cost and risk of developing new drugs.

To accomplish that goal, the new office will bring the FDA’s data-collection methods into the 21st century. Its work will include incorporating modern bioinformatics into data collection and analysis. It will also develop better ways to use tools like biomarkers—often blood-based measurements that indicate if a drug is working by its proposed mechanism of action—in evaluating new drugs. According to media reports, the office will formally launch in the first half of the year.

Advertisement

As the FDA contemplates how to improve the efficiency of developing and evaluating new drugs, companies are increasingly benefiting from government policies and incentives. The agency says that 73% of the drugs approved in 2018 used one or more of its pathways meant to speed the development process.

More drugs continue to be approved through the FDA’s breakthrough therapy status, an all-hands-on-deck incentive granted to drug candidates that work in highly innovative ways or treat serious diseases that lack therapies. In 2018, 14 new drugs were deemed breakthroughs, the second-highest number after the 17 approved with that status in 2017. The status has so far proved to be a good mechanism for shortening drug development time.

New high

Similarly, a hefty portion of new drugs were approved to treat orphan diseases—ones that affect fewer than 200,000 people. In 2018, 58% of the products, or 34 drugs, fell into that category, a significant jump from 2017, when 39% of therapies had orphan status. Last year’s orphan drugs include 13 of the 16 new cancer drugs approved, along with a bevy of treatments for extremely rare diseases, which can affect patient groups as small as a few dozen people.

The industry’s increasing focus on drugs for rare diseases concerns Peter B. Bach, director of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Center for Health Policy and Outcomes. While products that are first approved to treat an orphan disease sometimes go on to be approved for a broader patient group, a growing number treat a tiny slice of people at great expense.

“For a variety of policy and scientific reasons, companies are finding it more efficient to target conditions that affect very few people but have underlying molecular genetic drivers which are scientifically easier to target—and the time horizon on success or failure is shorter,” Bach says.

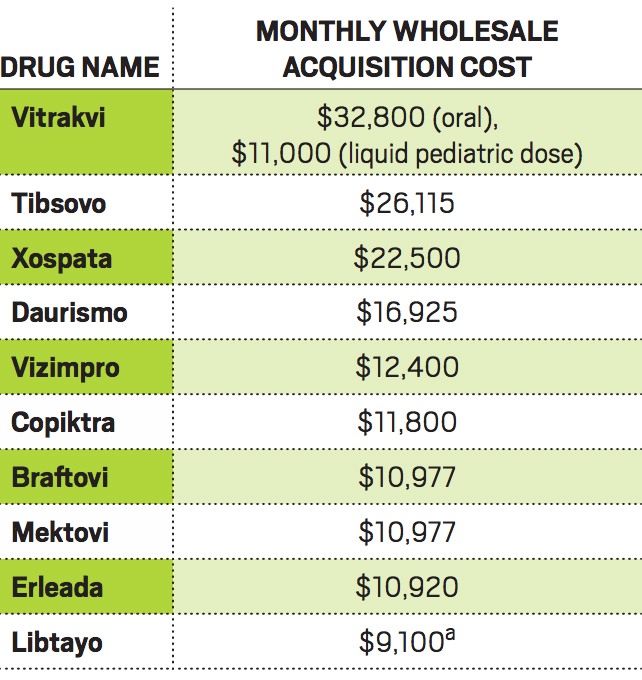

Costly drugs

a Cost is per three weeks.

Another problem, Bach says, is that companies use the size of the patient population to justify attaching hefty price tags to their drugs, despite the swifter path to success or failure.

Case in point is Loxo’s Vitrakvi, which is amazingly effective at shrinking tumors in people with TRK fusion mutations. The drug went from first patient trial to approval in about 3½ years, a breathtaking pace. But the mutation it treats is extremely rare, and Loxo and its partner, Bayer, have set an annual wholesale price for Vitrakvi of $393,600 for pills or $132,000 for a liquid for children and adults who can’t take pills.

A consequence of the industry’s focus on rare disease, Bach argues, is that “even if all of these drugs are wonderful—and some of them are pretty amazing—we’ve had the biopharma sector migrate to being more ‘moon-landing-amazing science one-offs,’ which won’t move the needle on public health.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter