Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Bisphenol A Under Scrutiny

Congress, media call into question safety of widely used plastics chemical

by Britt E. Erickson

June 2, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 22

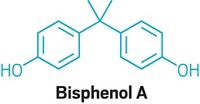

CONSUMER PRODUCTS containing bisphenol A (BPA), a high-production-volume chemical used to manufacture polycarbonate plastic and epoxy-based resins, have been on the market for more than 50 years. The chemical industry and federal regulatory agencies around the world insist that, on the basis of the available science, those products are safe when used as directed. But in the wake of a media firestorm and a congressional investigation centered on the use of BPA in baby bottles, infant formula cans, and everyday consumer goods, many retailers are bowing to consumer pressure and voluntarily pulling BPA-containing products off their shelves.

More than 2 billion lb of BPA is used annually in the U.S., according to ICIS Chemical Business. Most of that demand is for polycarbonate resins, which represents 75% of the market, followed by epoxy resins, which makes up 20% of the market. The rest goes into making miscellaneous products such as flame retardants.

BPA is found in numerous consumer products, from compact discs to bicycle helmets to automotive parts. But it's the food, beverage, and dental applications of BPA that have some researchers and activist groups riled up because those uses are thought to be the primary routes of human exposure. Almost all food and beverage cans are lined with epoxy resins made with BPA; dental sealants painted on children's teeth contain BPA; and many reusable plastic water bottles and food containers, including baby bottles, are made from BPA-containing polycarbonate plastic.

BPA was first synthesized in 1891, and its estrogenic properties were revealed in the 1930s. "We are only just now getting around to studying this chemical sufficiently to recognize its hazards after decades of widespread use in applications that clearly hold significant potential for exposure," says Richard Denison, a senior scientist with the nonprofit organization Environmental Defense Fund.

Those who want to see BPA—a known endocrine disrupter—banned from consumer products point to hundreds of studies published during the past decade that link low-level exposure with increased rates of prostate and breast cancer, reproductive abnormalities, decreased sperm count, accelerated puberty in females, neurological effects similar to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, diabetes, and obesity in laboratory animals (C&EN, Aug. 6, 2007, page 8).

The Environmental Protection Agency—the federal agency that regulates BPA—considers 50 mg per kg of body weight per day to be the lowest exposure level at which adverse effects can be discerned. After applying a safety factor, EPA has set an oral reference dose for BPA at 50 ??g/kg/day. Anything below that is considered safe. That safety standard, which went into effect in 1988, is the same standard that the Food & Drug Administration uses today to regulate how much BPA can migrate from food packaging.

"Back in the 1930s, the mantra was 'The dose makes the poison,' " says Mary Bachran, a research associate with the Endocrine Disruption Exchange. TEDX is a nonprofit group that aims to disseminate information about the effects of chemicals on the developing embryo and fetus. Bachran adds that earlier last century, regulators "didn't have a clue" about nonmonotomic responses; that is, as the dose goes down, the response goes up. The first "low dose" effects of BPA were reported in 1997, she says. Today, TEDX lists more than 300 such studies on its website.

But not everyone is buying the low-dose hypothesis. "Many of the studies investigating endocrine-modulating activity are essentially screening tests, and many employ experimental protocols that have not been validated. This information in conjunction with the known extensive metabolism of BPA to nonestrogenic metabolites provides a scientific basis for the lack of toxicological effects at low doses," says Steven G. Hentges, executive director of the American Chemistry Council's (ACC) Polycarbonate/BPA Global Group, which represents the plastics industry.

In August 2007, two government-convened groups came to nearly opposite conclusions regarding the health risks of low-level exposure to BPA (C&EN, Sept. 3, 2007, page 31). One group, made up of 38 scientists who had attended a workshop in November 2006 sponsored by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), reported that human exposure to BPA is within the range that causes adverse effects in laboratory animals.

The other group, established by the National Toxicology Program's (NTP) Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction (CERHR), an interagency group located on the NIEHS campus, expressed "some concern" regarding potential neurological effects from prenatal and early childhood exposures to BPA. However, they downplayed all other risks to adults, pregnant women, and unborn children.

Because of mounting allegations of industry influence on the CERHR panel and on the contractor facilitating the CERHR review, the panel reexamined the literature, including several low-dose studies it had omitted in its initial review. On April 14, NTP released its draft report on the health risks of BPA (C&EN, April 21, page 11), making essentially the same conclusions it did in August 2007. What was different this time was how various groups interpreted the phrase "some concern," which the report did not clearly quantify.

The chemical industry said the CERHR finding provided reassurance that BPA in consumer products is safe. "The NTP report did not say BPA is bad; it said there is some concern. You can make that statement about anything. That gives us confidence in the safety of BPA in all its multiple uses," says Jack N. Gerard, chief executive officer of ACC.

ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS, Congress, and the media, however, took the finding to mean the opposite and emphasized the report's concerns about prenatal and early childhood exposures to BPA. The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit group that has been trying to have BPA banned from children's products for years, said on its website that the NTP report "raised concerns that exposure to BPA during pregnancy and childhood could impact the developing breast and prostate, hasten puberty, and affect behavior in American children."

Following closely on the heels of the NTP draft report, Health Canada, the Canadian counterpart to FDA, released its draft assessment of BPA on April 18. This assessment concluded that "early development is sensitive to the effects of BPA." Canadian Minister of Health Anthony P. Clement acknowledged that although BPA "exposure levels to newborns and infants are below the levels that cause effects," he had decided it's "better to be safe than sorry" (C&EN, April 28, page 11). As a result, Health Canada announced plans to ban polycarbonate baby bottles and set limits on how much BPA can migrate from infant formula cans.

Meanwhile, because of a flurry of media reports in the U.S. about the health risks of BPA, the House of Representatives Committee on Energy & Commerce, led by Reps. John D. Dingell (D-Mich.) and Bart Stupak (D-Mich.), launched an investigation in January 2008 into the use of BPA in baby bottles and other products intended for infants and children. As part of that investigation, Congress learned that FDA based its determination that BPA is safe on two industry-funded studies, one of which is unpublished. In light of the findings and concerns raised by the NTP draft report and the Canadian risk assessment, the committee has asked FDA to reexamine its position on the safety of BPA.

"We would expect FDA to make decisions based on the best available science, especially when the health of infants and children is at stake," Stupak said in a statement. "Yet the FDA relied on only two industry-funded studies, while other respected authorities used all available data to reach vastly different conclusions. It is my hope that the FDA will revisit their decision and provide a truly independent analysis of the safety of bisphenol A." The investigation is ongoing, and more hearings are likely in the coming months.

On the Senate side, Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) recently introduced S. 2928, the BPA-Free Kids Act of 2008. The legislation would ban the use of BPA in all children's products, including baby bottles, teething rings, and sippy cups, as well as products from which no exposure is expected. This last grouping would include helmets, protective goggles, shin guards, and CDs.

"We buy things for our kids to keep them safe—shatter-resistant sippy cups, chip-proof baby bottles. And then we find out later that the very products that we thought would be safe could actually be much more dangerous for our children," Schumer said in a statement, adding that this is unacceptable. "Parents always err on the side of caution when it comes to their kids' health. We think that the law should do the same," he said.

Elsewhere in the Senate, the Commerce, Science & Transportation Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs, Insurance & Automotive Safety questioned officials from FDA and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) at a May 14 hearing on plastic additives in consumer products. Both agencies maintained their positions that BPA is safe in these products.

Norris Alderson, associate commissioner for science at FDA, testified before the Senate subcommittee that "at this time, FDA is not recommending that consumers discontinue using food contact materials that contain BPA. Although our review of the NTP report is continuing, a large body of available evidence indicates that food contact materials containing BPA currently on the market are safe and that exposure levels to BPA from these materials, including exposure to infants and children, are below those that may cause health effects."

To the same tune, Marilyn Wind, deputy associate executive director for health sciences at CPSC, emphasized the need to consider the beneficial use of polycarbonate when acting to prohibit BPA in children's products. "Such a ban could result in less-effective protection of children from head, eye, or bodily injury," she noted at the hearing.

To address growing concerns about BPA, Alderson told the subcommittee that in April, FDA formed an agency-wide BPA Task Force, which he chairs. The group is charged with reviewing current research and information about BPA in all FDA-regulated products, not just food and beverage containers, to shed light on all potential routes of exposure. The task force is examining concerns raised by the NTP draft report and the Canadian risk assessment, and if that review "leads us to a determination that uses of BPA are not safe, the agency will take action to protect the public health," Alderson said.

The chemical industry, however, is quick to point out that FDA's position on BPA is consistent with that of the European Food Safety Authority and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor & Welfare. The industry claims that decades of use without any unintended consequences is proof that BPA in consumer products on the market today is safe. It also says the science supports that conclusion. "There is more than 40 years of science surrounding BPA. The clear preponderance of that science points to when used as directed, there's not a problem," ACC's Gerard says.

The industry maintains that BPA has done much to improve the health and safety of consumers. Specifically, ACC's Hentges notes that BPA in canned-food liners provides real health benefits. "The primary function of the internal coating is to avoid food poisoning," adds John M. Rost, chairman of the North American Metal Packaging Alliance, an industry group that represents the metal food and beverage packaging industry. Without the coating, Escherichia coli and botulism poisoning would be rampant, he says.

IF CONGRESSIONAL ACTIVITY does result in a ban, finding alternatives for some items may be easier than others. For example, few alternatives exist today to replace epoxy-based resins in food and beverage cans, Rost tells C&EN.

"Groups have been working for a long time on alternatives to BPA in can liners," says Sara Risch, a professor who specializes in food-packaging interactions at Michigan State University. Most of that information, she says, is proprietary.

On the other hand, plenty of alternatives to polycarbonate water bottles and baby bottles already have begun flooding the market. In April, Nalgene announced that it is phasing out its polycarbonate reusable water bottles (C&EN, April 28, page 11). The company still considers its polycarbonate containers safe for their intended use, but says its customers have asked for BPA-free alternatives. Following Nalgene's announcement, some retailers pulled polycarbonate water bottles off their shelves; others slashed prices in hopes of selling off their remaining inventories.

Advertisement

To replace polycarbonate, bottle makers such as Nalgene and CamelBak have introduced a new line of water bottles made from an Eastman Chemical copolyester called Tritan. Several baby-bottle manufacturers have also pledged to eliminate BPA from their products, and many now offer BPA-free plastic alternatives.

Removing polycarbonate food and beverage containers from the market will likely have only a small impact on the BPA industry. ICIS Chemical Business estimates the 2007 demand for polycarbonate in the U.S. at 1.3 billion lb. Total packaging applications, including food and beverage containers, consume only 3% of that demand. The impact of removing epoxy resins from food and beverage cans is less clear. The Freedonia Group estimates the 2006 U.S. epoxy resin demand at 545 million lb. Epoxy resins used as coatings in metal food and beverage cans is not explicitly broken out, but rather, it is part of what the group calls other uses, which represent 43% of the total demand.

Regardless of whether BPA in everyday products poses a health risk, the recent press coverage and misinformation in blogs has confused consumers and policymakers alike. It has also contributed to the erosion of consumer trust in government, which has reached its lowest level in years.

"The industry and regulators have known about the effects of BPA for more than 10 years," says Jennifer Sass, a senior scientist with the environmental group Natural Resources Defense Council. "The public is just now realizing how long regulators have known about those effects and have failed to regulate or limit the use of BPA in consumer products," she says.

If there's one lesson that can be learned from BPA, it's look before you leap, say many environmental activists. They advocate taking a more cautionary approach before allowing new chemicals onto the market.

But those who make a living defending the safety of emerging technologies say they have seen this kind of hysteria before, calling it completely unjustified. "As with biotech foods, plastics brought huge gains in safety and have played no small role in the extension of life expectancy that we have seen in the past 100 years," says Val Giddings, a consultant for the biotech and nanotech industries and former vice president for food and agriculture at the Biotechnology Industry Organization.

Giddings remembers all too well the bad press that swirled around genetically modified foods more than a decade ago. "You have some professional protest groups that make money by peddling fear," he says. "Congress could take a giant step toward rectifying this kind of situation by reincarnating an organ for independent scientific advice, like the congressional Office of Technology Assessment."

The chemical industry isn't taking the BPA situation lightly and is ramping up its efforts to quell consumer fears and educate the public so that they understand the true value of the products, as well as the risks, ACC's Gerard says. "The key for the industry is to stay founded in the science."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter