Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Natural Products

Steven D. Townsend

Oligosaccharide explorer is solving the mysteries of breast milk sugars

by Lisa M. Jarvis

August 25, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 33

Vitals

Current affiliation: Vanderbilt University

Age: 36

PhD alma mater: Vanderbilt University

Role model: “I have two, Dirk Trauner and the late David Gin. Both are kind, brilliant, and inspiring human beings who operate at the nexus of organic chemistry and human health.”

If I were an element, I would be: Palladium. “It has changed the way we think about making C–C bonds more than any other metal. On a symbolic level, palladium is named after the asteroid Pallas, which is named after Pallas Athena—goddess of wisdom, skill, arts, and industry.”

Must-have in the lab: “The rotovap.”

Must-have on the road: “Wireless headphones to listen to hip-hop and R&B—most recently Big K.R.I.T. and Ella Mai.”

3 key papers

“Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) Sensitize Group B Streptococcus to Clindamycin, Erythromycin, Gentamicin, and Minocycline on a Strain Specific Basis” (ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00661)

“Human Milk Oligosaccharides Exhibit Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Properties against Group B Streptococcus” (ACS Infect. Dis. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00064)

At the tail end of his postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia University, Steven D. Townsend was struck by a curious trend in advertising. As he tooled around New York City with his wife, who was pregnant with their first child, he noticed that wealthy neighborhoods were dotted with signs advocating breastfeeding, while the posters hung around less affluent blocks focused on formula.

That very visible display of the disparity in women’s health in the US sparked something in Townsend. As the classically trained synthetic organic chemist mulled his independent career, he decided to veer into new territory—the study of human milk oligosaccharides.

Today, Townsend is one of a small but growing number of researchers trying to demystify the science of human breast milk, a topic that has been sorely underexplored. His work at Vanderbilt University spans efforts to synthesize the sugar molecules found in breast milk, understand the function and biological targets of those molecules, and identify compounds in breast milk that could have antibacterial properties.

Although the proteins and fats in breast milk are well understood by researchers, the sugars had been largely ignored. In fact, until about a decade ago, “people just thought human milk oligosaccharides were garbage—they had no purpose,” Townsend says.

His group’s first major paper proved that milk sugars are definitely not useless. In fact, they help protect infants against dangerous pathogens. Some sugars have antibacterial properties, while others help infection-fighting proteins do their job.

Those findings went viral, with headlines in both science outlets and the popular press. Townsend’s mom even called to say, “Oh my god, you were just on Fox News.”

The attention was hard won. By delving into an understudied area of science, Townsend initially had to convince others that his research was worthwhile. When he sent that first big paper on the relationship between oligosaccharides and infection to a prominent journal, it was promptly rejected. One of the reviewers even wrote, “We don’t know if human milk science is important.”

Most researchers simply didn’t grasp why breast milk was worth studying. “In the chemistry community, we’re just so far behind in understanding or deciphering the importance of milk,” Townsend says.

The chemist also had to branch into new fields of research—macromolecular chemistry, microbiology, and cellular imaging—to uncover milk oligosaccharides’ functions. Townsend did that through collaborations that taught him enough about new areas to bring them in-house. The result is what his former Columbia mentor, Samuel Danishefsky, calls “an outstanding multidisciplinary lab” that he compares to the approach taken by renowned chemical biologist Stuart Schreiber.

As Townsend helps bring the science of human milk sugars into the spotlight, the disparities in women’s health that Townsend saw so plainly on the streets of New York City continue to fuel his work. Formula companies, for example, have added the oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) to a number of products. But while 2′-FL is the most common oligosaccharide found in the breast milk of white women, 80% of whom harbor a gene that prompts their bodies to produce certain sugars, nonwhite populations more often have a mutation in that gene. As a result, “a lot of black and Latina women don’t produce the sugar,” Townsend says.

He is determined to probe the targets engaged by compounds like 2′-FL found in breast milk and understand whether shifting the balance of those sugars by adding them to formula might adversely affect an infant’s microbiome. “Ultimately, I want to make sure that people don’t break breast milk,” he says.

At the tail end of his postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia University, Steven D. Townsend was struck by a curious trend in advertising. As he tooled around New York City with his wife, who was pregnant with their first child, he noticed that wealthy neighborhoods were dotted with signs advocating breastfeeding, while the posters hung around less affluent blocks focused on formula.

That very visible display of the disparity in women’s health in the US sparked something in Townsend. As the classically trained synthetic organic chemist mulled his independent career, he decided to veer into new territory—the study of human milk oligosaccharides.

Advertisement

Today, Townsend is one of a small but growing number of researchers trying to demystify the science of human breast milk, a topic that has been sorely underexplored. His work at Vanderbilt University spans efforts to synthesize the sugar molecules found in breast milk, understand the function and biological targets of those molecules, and identify compounds in breast milk that could have antibacterial properties.

Although the proteins and fats in breast milk are well understood by researchers, the sugars had been largely ignored. In fact, until about a decade ago, “people just thought human milk oligosaccharides were garbage—they had no purpose,” Townsend says.

His group’s first major paper proved that milk sugars are definitely not useless. In fact, they help protect infants against dangerous pathogens. Some sugars have antibacterial properties, while others help infection-fighting proteins do their job.

Those findings went viral, with headlines in both science outlets and the popular press. Townsend’s mom even called to say, “Oh my god, you were just on Fox News.”

The attention was hard won. By delving into an understudied area of science, Townsend initially had to convince others that his research was worthwhile. When he sent that first big paper on the relationship between oligosaccharides and infection to a prominent journal, it was promptly rejected. One of the reviewers even wrote, “We don’t know if human milk science is important.”

Most researchers simply didn’t grasp why breast milk was worth studying. “In the chemistry community, we’re just so far behind in understanding or deciphering the importance of milk,” Townsend says.

The chemist also had to branch into new fields of research—macromolecular chemistry, microbiology, and cellular imaging—to uncover milk oligosaccharides’ functions. Townsend did that through collaborations that taught him enough about new areas to bring them in-house. The result is what his former Columbia mentor, Samuel Danishefsky, calls “an outstanding multidisciplinary lab” that he compares to the approach taken by renowned chemical biologist Stuart Schreiber.

As Townsend helps bring the science of human milk sugars into the spotlight, the disparities in women’s health that Townsend saw so plainly on the streets of New York City continue to fuel his work. Formula companies, for example, have added the oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) to a number of products. But while 2′-FL is the most common oligosaccharide found in the breast milk of white women, 80% of whom harbor a gene that prompts their bodies to produce certain sugars, nonwhite populations more often have a mutation in that gene. As a result, “a lot of black and Latina women don’t produce the sugar,” Townsend says.

He is determined to probe the targets engaged by compounds like 2′-FL found in breast milk and understand whether shifting the balance of those sugars by adding them to formula might adversely affect an infant’s microbiome. “Ultimately, I want to make sure that people don’t break breast milk,” he says.

Vitals

Current affiliation: Vanderbilt University

Age: 36

PhD alma mater: Vanderbilt University

Role model: “I have two, Dirk Trauner and the late David Gin. Both are kind, brilliant, and inspiring human beings who operate at the nexus of organic chemistry and human health.”

If I were an element, I would be: Palladium. “It has changed the way we think about making C–C bonds more than any other metal. On a symbolic level, palladium is named after the asteroid Pallas, which is named after Pallas Athena—goddess of wisdom, skill, arts, and industry.”

Must-have in the lab: “The rotovap.”

Must-have on the road: “Wireless headphones to listen to hip-hop and R&B—most recently Big K.R.I.T. and Ella Mai.”

Research at a glance

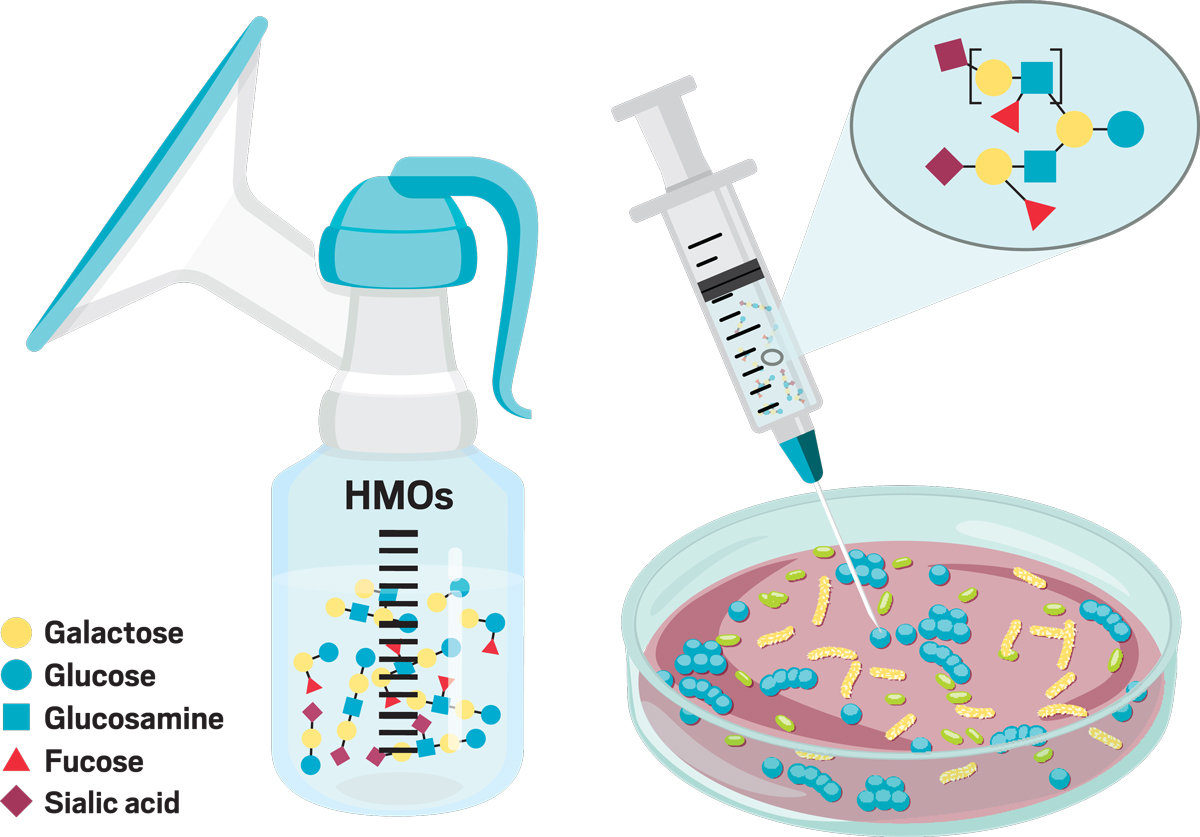

Credit: Shutterstock/Yang H. Ku/C&EN

Townsend isolates and studies the biological function of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which he has found can break up bacterial biofilms.

Three key papers

“Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) Sensitize Group B Streptococcus to Clindamycin, Erythromycin, Gentamicin, and Minocycline on a Strain Specific Basis”

(ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00661)

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter