Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Polymers

Frank Leibfarth

Polymer powerhouse is tapping organic chemistry insights to build better plastics

by Bethany Halford

August 25, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 33

Vitals

Current affiliation: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Age: 34

PhD alma mater: University of California, Santa Barbara

Role model: “Carolyn Bertozzi: she is a world-class scientist, a fantastic communicator, a vocal advocate to make science more inclusive, and a great representative for our discipline.”

I’ve overcome adversity in the lab by: “I suffered from a crippling sense of impostor syndrome during my graduate career. I finally broke through by beginning to express myself through writing recurring blog posts for The Sceptical Chymist, Nature Chemistry’s blog site. Being from a humble background, I always felt like an outsider in science; establishing my independent voice allowed me to gain self-confidence and realize that I could contribute something meaningful through my own creative pursuits.”

Must-have in the lab: “Music. I love walking into lab each day and hearing the music choice of the day. It’s one of the little ways that the students can express themselves and put their stamp on the collective lab environment.”

Must-have on the road: “Probably one of my largest personal purchases was a high-end carry-on garment bag. This bag is the perfect size, easy to carry, organizes and fits a ton of items, and is indestructible.”

3 key papers

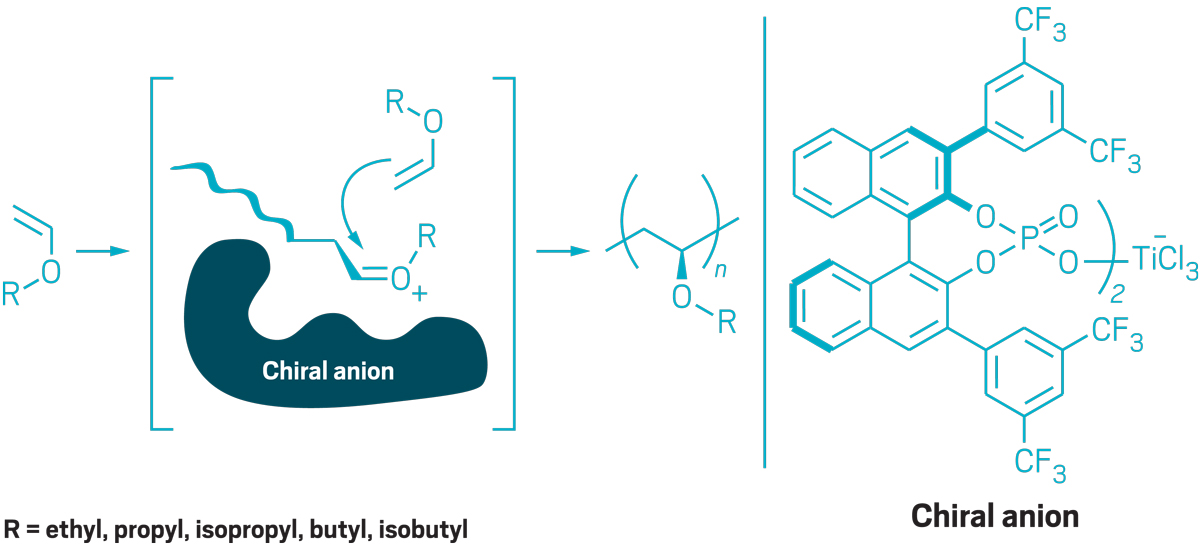

“Catalyst-Controlled Stereoselective Cationic Polymerization of Vinyl Ethers” (Science 2019, DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw1703)

“Hope for Graduate School Childbirth Policies” (Science 2011, DOI: 10.1126/science.333.6048.1380-a)

“A Facile Route to Ketene-Functionalized Polymers for General Materials Applications” (Nat. Chem. 2010, DOI: 10.1038/nchem.538)

As the kicker on the University of South Dakota’s football team, Frank Leibfarth had moments when he stepped onto the field knowing that his single kick would determine whether his team won or lost. “Before you can ever make a game-winning field goal, you have to know you can handle missing one,” Leibfarth says. “You can’t be scared to fail when you walk out there.”

People who have worked with Leibfarth say that experience has served him well. “He embodies one of the traits that I consider most important in research—fearlessness,” says the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Timothy Jamison, Leibfarth’s postdoctoral mentor. “Combined with his record of accomplishment, scholarship, creativity, and ambition, Frank’s desire to step outside his comfort zone made me confident that he would be an exceptional independent scientist, one who will lead a vibrant and leading research program. I am delighted to see that this prediction has already materialized.”

Earlier this year, Leibfarth, now a chemistry professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, scored big with an advance in polymers—the field in which he did his doctoral work with Craig Hawker at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Leibfarth figured out a way to tweak the synthesis of a family of polymers so that the stereochemical arrangement of its side chains was controlled rather than random.

With the random side-chain arrangement, the polymers—poly(vinyl ethers)—were viscous liquids with niche applications as adhesives. Creating the polymers with stereocenters that are all the same (or isotactic, as polymer chemists say) made them solid with properties akin to, and in some respects better than, those of commercial polyolefins. For an idea of the potential impact, consider that each year more than 100 million metric tons of polyolefins are produced, according to the PlasticsEurope Market Research Group, to make things like toys, tennis racket strings, and food packaging.

Figuring out how to make poly(vinyl ethers) isotactically has been a long-standing problem for polymer chemists. That’s because the oxygen atoms in vinyl ether monomers poison the catalysts that are used to make isotactic polyolefins. Leibfarth’s insight was to use chiral anion catalysis, an approach that’s more commonly used to make small molecules.

It wasn’t always clear that Leibfarth’s calling was in chemistry. He decided not to pursue biology after he spent a summer extracting DNA from dead fleas. The following summer he worked in Colin Nuckolls’s lab at Columbia University as part of the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates program.

“That experience changed my life,” Leibfarth says. It was his first chance to do cutting-edge research. “Being an athlete, I’m driven by competition,” he explains. “The idea that I could have that outlet within science was really exciting.”

Keeping the long game in mind, Leibfarth wants to build polymers that are easier to break down. “The largest impact will come from how we make these things,” he says, “because once they’re made, they don’t really go away.”

Advertisement

As the kicker on the University of South Dakota’s football team, Frank Leibfarth had moments when he stepped onto the field knowing that his single kick would determine whether his team won or lost. “Before you can ever make a game-winning field goal, you have to know you can handle missing one,” Leibfarth says. “You can’t be scared to fail when you walk out there.”

People who have worked with Leibfarth say that experience has served him well. “He embodies one of the traits that I consider most important in research—fearlessness,” says the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Timothy Jamison, Leibfarth’s postdoctoral mentor. “Combined with his record of accomplishment, scholarship, creativity, and ambition, Frank’s desire to step outside his comfort zone made me confident that he would be an exceptional independent scientist, one who will lead a vibrant and leading research program. I am delighted to see that this prediction has already materialized.”

Advertisement

Earlier this year, Leibfarth, now a chemistry professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, scored big with an advance in polymers—the field in which he did his doctoral work with Craig Hawker at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Leibfarth figured out a way to tweak the synthesis of a family of polymers so that the stereochemical arrangement of its side chains was controlled rather than random.

With the random side-chain arrangement, the polymers—poly(vinyl ethers)—were viscous liquids with niche applications as adhesives. Creating the polymers with stereocenters that are all the same (or isotactic, as polymer chemists say) made them solid with properties akin to, and in some respects better than, those of commercial polyolefins. For an idea of the potential impact, consider that each year more than 100 million metric tons of polyolefins are produced, according to the PlasticsEurope Market Research Group, to make things like toys, tennis racket strings, and food packaging.

Figuring out how to make poly(vinyl ethers) isotactically has been a long-standing problem for polymer chemists. That’s because the oxygen atoms in vinyl ether monomers poison the catalysts that are used to make isotactic polyolefins. Leibfarth’s insight was to use chiral anion catalysis, an approach that’s more commonly used to make small molecules.

It wasn’t always clear that Leibfarth’s calling was in chemistry. He decided not to pursue biology after he spent a summer extracting DNA from dead fleas. The following summer he worked in Colin Nuckolls’s lab at Columbia University as part of the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates program.

“That experience changed my life,” Leibfarth says. It was his first chance to do cutting-edge research. “Being an athlete, I’m driven by competition,” he explains. “The idea that I could have that outlet within science was really exciting.”

Keeping the long game in mind, Leibfarth wants to build polymers that are easier to break down. “The largest impact will come from how we make these things,” he says, “because once they’re made, they don’t really go away.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Age: 34

PhD alma mater: University of California, Santa Barbara

Role model: “Carolyn Bertozzi: she is a world-class scientist, a fantastic communicator, a vocal advocate to make science more inclusive, and a great representative for our discipline.”

I’ve overcome adversity in the lab by: “I suffered from a crippling sense of impostor syndrome during my graduate career. I finally broke through by beginning to express myself through writing recurring blog posts for The Sceptical Chymist, Nature Chemistry’s blog site. Being from a humble background, I always felt like an outsider in science; establishing my independent voice allowed me to gain self-confidence and realize that I could contribute something meaningful through my own creative pursuits.”

Must-have in the lab: “Music. I love walking into lab each day and hearing the music choice of the day. It’s one of the little ways that the students can express themselves and put their stamp on the collective lab environment.”

Must-have on the road: “Probably one of my largest personal purchases was a high-end carry-on garment bag. This bag is the perfect size, easy to carry, organizes and fits a ton of items, and is indestructible.”

Research at a glance

Credit: Adapted from Science/Yang H. Ku/C&EN

Leibfarth uses chiral catalysts to make poly(vinyl ethers) that have side chains with uniform stereochemistry. As the polymer chain grows, a chiral anion blocks one side, so the monomer can add to only the opposite side.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter