Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biobased Chemicals

Renewable chemical maker Avantium tries for an encore performance

After attracting BASF, catalysis expert seeks other partners for a new batch of projects

by Marc S. Reisch

June 11, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 24

Can Avantium do it again? In 2016, the Dutch renewable chemical developer snagged a deal worth up to $700 million with the big chemical maker BASF. The two firms formed a joint venture to bring a sugar-derived polymer, polyethylene furanoate (PEF), to market.

On the strengths of that deal, Avantium raised more than $100 million last year in an initial public offering of stock. The joint venture, called Synvina, will use a large chunk of that cash to commercialize PEF as a renewable alternative to the ubiquitous petroleum-derived polymer polyethylene terephthalate.

Avantium at a glance

▸ Headquarters: Amsterdam

▸ Revenues: $14.4 million

▸ Operating loss: $11.4 million

▸ Employees: 139

Current business:

▸ Catalysis: A research service for chemical, refinery, and energy customers

Businesses under development:

▸ Synvina: A 49%-owned joint venture with BASF to develop and license technology to make polyethylene furanoate

▸ Zambezi: A project to convert biomass to sugar

▸ Mekong: A project to convert glucose to ethylene glycol in one step

▸ Volta: A project to electrocatalytically convert carbon dioxide to chemical building blocks

Note: Figures are for 2017.

But Avantium also has three other renewable chemical projects under way: making sugars from nonfood biomass, converting sugar to ethylene glycol, and electrochemically converting carbon dioxide to chemical building blocks. It now seeks a repeat performance in biobased chemicals despite heightened competition from traditional chemicals because of low oil prices.

Gert-Jan Gruter, Avantium’s chief technology officer, says the firm is searching for partners who can help develop the three new projects. “Our objective is to develop winning technologies,” he says.

Gruter knows that other companies with similar renewable chemical objectives have found that breakthrough technology doesn’t guarantee success. Failures include two biomass-to-ethanol plants: Abengoa’s Kansas project and Mossi Ghisolfi Group’s Beta Renewables venture. The first shut down in 2015 and the second in 2017, both because of financial problems.

Rennovia, a developer of biobased nylon raw materials, also shut down last year because of liquidity problems and low petrochemical prices, according to industry reports. And earlier this year, the biobased succinic acid maker BioAmber entered bankruptcy reorganization.

Synvina will have the dual challenge of rolling out a brand-new material while competing against firms such as DuPont and Corbion, which are also developing biobased furanic packaging polymers.

But at least for now, money shouldn’t be a problem. Funds raised in the stock offering should keep Avantium going for another three to four years, says Wim Hoste, a senior financial analyst with KBC Securities, a Belgian investment firm. Cash on hand will allow Avantium to build pilot plants for its newest projects and to fund its share of the Synvina joint venture.

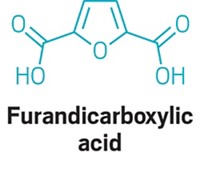

However, when Synvina starts to build its planned 50,000-metric-ton-per year furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) plant at BASF’s Antwerp, Belgium, site in about 2022, Avantium will need to put up more cash, Hoste warns. FDCA is the sugar-derived feedstock needed to make PEF. The money could come from licenses that Synvina hopes to sell to make FDCA and PEF; otherwise, Avantium will have to raise funds from investors, Hoste says.

Avantium has long had a hand in developing what Gruter refers to as “winning technologies” for its customers. Founded in 2000 as a spin-off from the energy and petrochemical giant Shell, the firm started out as a contract research organization. It has kept the lights on in large part by doing high-throughput research to improve catalysts for Shell as well as oil and chemical firms such as BP, Celanese, Dow Chemical, ExxonMobil, and SABIC.

Advertisement

In 2005, Gruter says, Avantium began to develop the technology and catalysts to make FDCA and PEF. Even before the formation of Synvina, the project attracted outside investors. Notably, in 2014 it got $50 million from a consortium of firms, including food and beverage giants Coca-Cola and Danone, to validate PEF and design a PEF plant. Synvina currently operates three pilot-sized FDCA plants in the Netherlands, Gruter says.

On the face of it, Avantium has a split personality. On the one hand it researches catalysts for old-line, fossil-fuel-based clients, and on the other it develops renewable chemical catalytic processes on its own behalf.

Gruter, who is listed as an inventor on more than 200 patents and patent applications, says, “The research we need to test catalysts for demanding customers helps our own R&D. That research is an enabling technology for both sides of our business.”

Avantium may eventually end up competing against its customers. For now, Gruter says, “there is enough room for conventional and renewable polymers.”

While Avantium has told investors it can go it alone on its three renewable chemical projects or even sell them off, partnering with others to develop and then license the technology is the preferred business model.

In the case of its project to make sugars from biomass, the firm put together a consortium early in 2017 that includes the Dutch chemical maker AkzoNobel and the German energy firm RWE. Avantium is now building a pilot plant at AkzoNobel’s site in Delfzijl, the Netherlands, to turn wood residue into high-purity glucose, lignin, and a mixed-sugar syrup. AkzoNobel will supply the hydrochloric acid that Avantium needs to break down locally sourced wood chips.

The prize in this process is the glucose, which can be used to make vitamins, enzymes, and other chemicals such as FDCA, ethylene glycol, lactic acid, and succinic acid. The mixed syrup can be used to make ethanol, and the energy-dense lignin can replace coal in RWE’s power plants.

Gruter says Avantium is also talking to potential partners about the scale-up of its one-step catalytic process for turning glucose into ethylene glycol. “We almost killed this project two or three times because it was so challenging,” he says. But now Avantium is starting to build a pilot plant at a soon-to-be-announced site. “We are funding the plant on our own,” he says.

The third project still needs more work, Gruter says. The firm is developing a catalytic electrochemical cell to convert carbon dioxide to valuable chemicals such as oxalic acid and formic acid. Avantium combined its own activities in this area with those of the New Jersey start-up Liquid Light, which it purchased in 2017.

“It will be another two to three years before we have a cell ready for scale-out,” Gruter says. For now, the firm has some European Union funding to help pay for the research, he says.

Additional projects, centered on new polymers, are on the drawing boards at Avantium, but they are too early to talk about, Gruter says. Moving along the three existing projects would seem to come down to attracting new partners. One like BASF wouldn’t hurt.

For now, says Hoste, the financial analyst, “investors are focused on Synvina and Avantium’s PEF process.” Which is not without its challenges: The partners recently pushed the FDCA plant back by two years to iron out production problems. For Avantium, having a successful encore may require perfecting its main act first.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter