Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Cosmetics that take on the stresses of modern life

As consumers worry about light and air pollution, personal care formulators look for ways to safeguard skin from blue light and other environmental assaults

by Marc S. Reisch

May 14, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 20

Credit: C&EN/Shutterstock

In brief

Environmental pollutants are taking on significance as skin care formulators seek more sales and pursue new strategies to protect the body’s largest organ from premature wrinkling, dark spots, and uneven tone. Companies are enlisting science to come up with defenses against diesel fumes, cigarette smoke, and particles in the air. Polymeric shields and antioxidants are among the latest weapons. Formulators are also gearing up to protect skin against blue light emitted from the screens of electronic devices. In this battle, they’re adapting light-shielding screens and recruiting an arsenal of antioxidants to preserve and protect skin.

In 1912, Pond’s advised female motorists driving through the countryside in open-air cars to protect their skin with its Vanishing Cream. “Dust poisons your skin,” the advertising copy read, and it “gets down into the pores and acts as a poison.”

Cosmetic formulators and the ingredient companies that supply them give pretty much the same spiel today. Only now they point to environmental pollutants such as diesel and cigarette smoke particulates. Or they finger the blue light radiating from cell phone, tablet, and computer screens as disruptors of people’s circadian rhythms.

Pond’s promised its Vanishing Cream was “most effective in keeping your skin clear, transparent and delicate” by using “one of the most valuable skin-softening ingredients that modern chemistry has placed at the service of woman.” Glycerin was at the heart of the cream’s success.

Contemporary cosmetics-ingredient makers no longer lead pitches to customers with “chemistry,” but they still rely on it. Their arsenal includes natural extracts with antioxidant properties and film-forming ingredients that guard skin against premature wrinkling and dark spots. Skeptics will argue that grime and blue light are hardly scourges of the skin. But ingredients that purportedly combat them help cosmetics-industry customers keep sales humming.

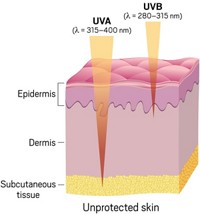

Most knowledge about the effects of light on skin is based on investigations into the effects of ultraviolet-A and ultraviolet-B rays, dermatologist Nada Elbuluk says. But “UV radiation only accounts for 7% of sunlight. The rest is visible and infrared light,” she says.

In recent years, says Elbuluk, who is an assistant professor at New York University’s medical school, researchers have become interested in understanding the impact of visible light. “What we do know is that light exposure in general can increase skin pigmentation, especially in patients with pigment disorders,” she says. But the jury is still out on whether a person can be exposed to enough blue light from the screens of electronic devices to make any difference.

On the other hand, excessive exposure to environmental pollutants clearly can irritate skin, Elbuluk notes, and exposure to cigarette smoke can damage it. However, she is unwilling to suggest that pollutants such as diesel particulates can contribute to skin aging.

Soap and water twice a day can go a long way to wash off dirt-caused skin irritation, Elbuluk notes. People who work in certain industries, such as construction, may be exposed to high levels of small particles and want to take additional precautions, such as wearing protective clothing, she suggests.

Seeing an opportunity to sell a pricier solution than soap and water, cosmetics makers have seized on concerns over blue light and environmental pollutants.

Interest in pollution protection came first, says Vivienne Rudd, director of global innovation and insight at the market research firm Mintel. The firm was clued in to concerns over blue light about five years ago when opticians began to sell eyewear to block blue light under the theory that it contributed to eye strain and age-related macular degeneration, a leading cause of blindness.

For instance, Essilor, a large provider of eyeglass lenses and coatings, started alerting eye-care specialists about overexposure to what it called “harmful blue-violet light” between 415 and 455 nm. Blue light, just below ultraviolet, covers the spectrum from 380 to 500 nm.

Essilor used its research to suggest that the sun and “electronic devices and screens” as sources of blue light emissions that could lead to age-related macular degeneration. As a solution, the firm offers lens coatings that block the purportedly harmful blue light.

“We also began to see scientific papers suggesting that blue light penetrated the skin, causing hyperpigmentation,” Rudd says. For instance, one recent study appearing in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology links blue light and skin pigment regulation (2017, DOI:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.833).

In addition, recent Mintel consumer surveys show budding consumer concern over blue light, with some people seeing a link to other forms of radiation, such as the ultraviolet sun rays that cause wrinkling, sunburn, and skin cancer, Rudd notes.

Rudd says she would not be surprised if all-spectrum light protection catches on in the future. Already at the cosmetics counter today is Ma Vap’ Bien Aimée makeup-fixing mist, from the French cosmetics firm Garancia, which promises to protect skin from pollution and blue light. Another example is Perfect Block, a sun “multiprotector” for the face and body from Peru’s Ésika. It promises UV-A, UV-B, infrared, and visible-light protection.

In addition to blue light’s possible connection to macular degeneration and hyperpigmentation, scientists know that it is important for color perception and circadian rhythm synchronization.

Just below ultraviolet light and still on the visible spectrum, blue light is believed to penetrate more deeply into the skin’s dermis.

Blue light receptors in the eye suppress the release of melatonin, the hormone that induces sleep. If those receptors continue to receive blue light at night, sleep patterns are disrupted—hence the common admonition not to check your phone before bed. For those who ignore the advice, one line of defense, reasons Alexandre Lapeyre, global technical marketing manager for ingredient maker Clariant, is to work with skin cells’ own circadian rhythms.

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which laid out the molecular mechanisms driving organisms’ inner biological clocks, inspired Clariant’s approach, Lapeyre says. “The theory is that skin cells have their own circadian rhythm,” he explains. “Stresses like blue light from a cell phone or tablet screen late at night, jet lag, and intense lifestyles disrupt the normal circadian rhythm of skin cells.”

These stresses also disrupt skin hydration and detoxification pathways that are rhythm dependent, he adds. To restore the skin’s normal circadian cycle, Clariant developed an extract from Lespedeza capitata, a plant grown and harvested in South Korea for medicinal use.

The plant, Lapeyre explains, has its own circadian cycle: Its leaves and flowers open during the day and close at night. Two glycosylated flavonoids that maintain that cycle—carlinoside and isoschaftoside—are part of the extract that Clariant calls B-Circadin.

Lapeyre says the flavonoids help resynchronize the skin cells’ circadian rhythm. Users of B-Circadin might dance the night away and still look fresh, if the extract lives up to its billing. “The product works no matter the time of day,” he says.

Another strategy to combat the impact of blue light is to treat skin with an antioxidant. “Blue light is a form of high-energy visible light,” says Anne Clay, skin care marketing manager for Ashland. It can cause skin inflammation and deplete protective carotenoids in the skin, she says.

Ashland developed Blumilight, an extract of cocoa seeds that contains peptides, saccharides, and polyphenols. The extract, Clay maintains, protects against the formation of wrinkles caused by blue light, an effect she refers to as digital aging.

Other strategies to reduce blue light exposure involve light blockers. Most traditional sunscreens block UV-A and UV-B light, says Rolf Schütz, a study director at DSM, which supplies UV filters and other cosmetic ingredients. But a combination of titanium dioxide and methylene bis-benzotriazolyl tetramethylbutylphenol (MBBT) can effectively provide UV protection and prevent up to 50% of blue light from reaching the skin, he says.

Schütz recommends that blue-blocking formulas also include niacinamide and tocopherols, two vitamins with antioxidant properties. The vitamins, he says, prevent the formation of reactive oxygen species, which worsen skin aging.

While the greatest exposure to blue light comes from the sun, indoors the source of much of this blue light is light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which are used to illuminate phone and tablet screens and are increasingly used as a source of lighting in homes and businesses.Though they appear to be white, LEDs typically expose people to more light from the blue end of the spectrum than do incandescent light sources, which tend to emit more yellow and red. “We are engaging in a long-term experiment in human exposure to blue light indoors,” Schütz points out.

On average, people spend more than four hours a day exposed to such light sources in the U.S. and Japan, Schütz says. In the U.K., France, and Germany, average exposure is more than three hours a day. “We’re not sure what the consequences are of long-term, chronic exposure to blue light,” he says.

BASF, another maker of traditional UV sunscreens, is also adapting existing sunscreens for blue light attenuation. It has created a model formulation called All Rays UV Protection that Markus Schwind, sun care marketing manager, calls “a smart combination of UV sunscreens from the last 15 years.”

Like the DSM formula, All Rays incorporates MBBT. It also includes tris-biphenyl triazine (TBPT). The two ingredients absorb and scatter UV and blue light, Schwind says.

Filters that protect wearers from visible light aren’t government regulated like those for the UV range, he points out. “The aim going forward should be to give consumers a sort of blue light protective factor” that would be comparable to the sun protection factor number for UV light now on sunscreen bottles, Schwind says. Without an industry standard, it’s hard for consumers to know how much protection a skin care formula offers.

Advertisement

He also wonders how much blue light protection consumers need indoors and from their electronic devices. Skin exposure to blue light from a day at the beach is undoubtedly many times greater than exposure from a smartphone screen, Schwind says. “We still need to learn more about how human skin reacts to blue light.”

One thing we do know is that blue light can penetrate more deeply into the skin than UV light, notes Samanta Maci, a technical manager for Kemin, maker of FloraGLO Lutein, a carotenoid extract from marigold flowers. On the skin, lutein absorbs blue light and prevents the oxidation of skin-protecting lipids by sunlight, Maci says.

She sees justification for protecting people from blue light emitted by electronic devices. The light to which users are exposed outdoors is more intense than what they get indoors and in front of their electronic devices. But the duration of the indoor exposure and the fact that users get so close to their devices mean they could get damaging doses of blue light, Maci says.

A natural alternative to synthetic blue blockers, Kemin’s lutein is already widely used as an oral supplement, mostly to protect the macula portion of the eye’s retina, explains Ceci Snyder, Kemin’s vision products manager. Some formulators are already using lutein in skin creams, though it will “turn a product a little orange,” she says.

Sources: Companies

Marketing concepts like blue light and pollution are important for the skin care business, says Nikola Matic, chemical and materials manager at the consulting firm Kline & Co. But whereas questions about blue light abound, the effects of environmental pollutants seem clear.

“While we don’t know enough about blue light yet, pollution is proven to have an adverse impact on skin,” he says. “If you are living in Beijing, which is well known for its air pollution problems, your skin would probably benefit from a film-forming material or an active ingredient with antioxidant properties.”

Film formers could be a first line of defense against airborne particles. One film former, from the Brazilian firm Chemyunion, consists of a chia-seed-derived polysaccharide. It acts as a selective barrier against particulate matter that causes inflammation, dark spots, and accelerated skin aging.

Called SkinBlitz, the film former is tested to decrease penetration of lead and arsenic from pollutants such as cigarette smoke and from gasoline combustion, where lead additives haven’t been banned. Cristiane R. da Silva Pacheco, a Chemyunion vice president, notes that SkinBlitz prevents but does not repair skin damage from heavy-metal pollutants.

But other firms do offer products that purportedly repair damage from small particles in the air, particularly those found in industrial and city centers. Lapeyre, the Clariant technical marketing manager, notes that heavy metals, particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—the result of incomplete combustion—and gaseous pollutants can all penetrate skin.

Inside the skin, such pollutants induce formation of reactive oxygen species, causing collagen degradation and irritation, he says. All that nastiness will lead to dry skin and premature signs of aging.

RedSnow, a derivative of Camellia japonica flowers, blocks pathways leading to oxidation and irritation, Lapeyre says. Key to the action that RedSnow promises is a phenolic compound known as protocatechuic acid, he says.

Indoor air pollution is something to be concerned about as well, Lapeyre points out. In developed countries, people spend about 90% of their time indoors and are exposed to pollutants from household products, tobacco smoke, dust, heavy metals, and particulate matter, he says.

These pollutants and allergens cause a vicious cycle of reactions in skin cells. As a result, skin becomes dry, irritated, and itchy, Lapeyre says. Clariant screened a number of extracts and found a solution in one from Citrus unshiu.

The extract, which Clariant calls Eosidin, is rich in synephrine, hesperidin, and naringin. Lapeyre says these molecules effectively block the cascade of reactions in skin cells that lead to the release of histamine, which causes itchy skin.

Also getting into the act with an antioxidant is Dow Chemical. Best known as a supplier of rheology modifiers, conditioners, surfactants, resins, and silicones, the big firm has developed a synthetic antioxidant it calls AgeCap Smooth.

The ingredient, methoxylhydroxyphenyl isopropylnitrone, is promoted as protection from “external aggressive factors” and is intended to keep skin smooth as people age. Jon Fedders, a Dow marketing director, says AgeCap is a “new-to-the-world chemistry” whose performance is similar to or exceeds that of the antioxidants retinol and vitamin C.

Fedders says Dow is interested in bringing more science-based solutions to skin care. The firm recently began a three-year collaboration with two European schools—the University of Ferrara and the University of Fribourg—and Stanford University to study the impact of air pollution on skin and to develop ingredients to protect the skin against urban pollution.

The European Union is underwriting part of the cost of the study under Horizon 2020, a seven-year, $100 billion program meant to boost innovative research. The project in which Dow is involved will support three graduate students and other researchers at the schools for three years.

The extent to which cosmetics can ameliorate the effects of pollution and blue light is certainly debatable. Karl Lintner, formerly chief executive of the active ingredient maker Sederma, now part of Croda, says out loud what others in the industry may well think.

“Yes, we want to protect skin,” says Lintner, who heads his own Paris-based consulting firm, KAL’idées. “But to single out one wavelength of light or another seems arbitrary and too simple.”

“Create a story and sell it. That’s cosmetics,” Lintner says. “It’s all about business, and it’s all fun. As long as you don’t cheat and don’t lead consumers into danger by saying things that are totally absurd, you are all right.”

“We do need science to tell a story,” Lintner says, but cosmetics are “all about the guilty pleasure of splurging on something that smells and feels good.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter