Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Covid-19

What is hand sanitizer, and does it keep your hands germ-free?

Useful when you don’t have access to a sink and some soap, hand sanitizers have become a hot commodity in the face of COVID-19

by Laura Howes

March 23, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 12

In early 2020, as the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, spread, hand sanitizer sales began to grow. By March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially upgraded the outbreak to a global pandemic. Health agencies everywhere recommended that people refrain from touching their faces and clean their hands after touching public surfaces like door handles and handrails.

The first US case of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, was detected Jan. 20. According to market research firm Nielsen, hand sanitizer sales in the US grew 73% in the 4 weeks ending Feb. 22.

Support nonprofit science journalism

C&EN has made this story and all of its coverage of the coronavirus epidemic freely available during the outbreak to keep the public informed. To support us:

Donate Join Subscribe

Signs have begun to spring up on storefront doors across the globe explaining that hand sanitizers are sold out. As a result, luxury brand owner LVMH, chemical giant BASF, and chemistry students at different universities across the globe are trying to produce fresh supplies.

But is the popularity of hand sanitizers justified? Although most health officials say that soap and water is the best way to keep your hands virus-free, when you’re not near a sink, the experts say, hand sanitizers are the next best thing. To get the maximum benefit from hand sanitizers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that people use a product that contains at least 60% alcohol, cover all surfaces of their hands with the product, and rub them together until dry.

Even before scientists knew that germs existed, doctors made the link between handwashing and health. American medical reformer Oliver Wendell Holmes and the Hungarian “Savior of Mothers,” Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis, both linked poor hand hygiene with increased rates of postpartum infections in the 1840s, almost 20 years before famed French biologist Louis Pasteur published his first germ theory findings. In 1966, while still a nursing student, Lupe Hernandez patented an alcohol-containing, gel-based hand sanitizer for hospitals. And in 1988, the firm Gojo introduced Purell, the first alcohol-containing gel sanitizer for consumers.

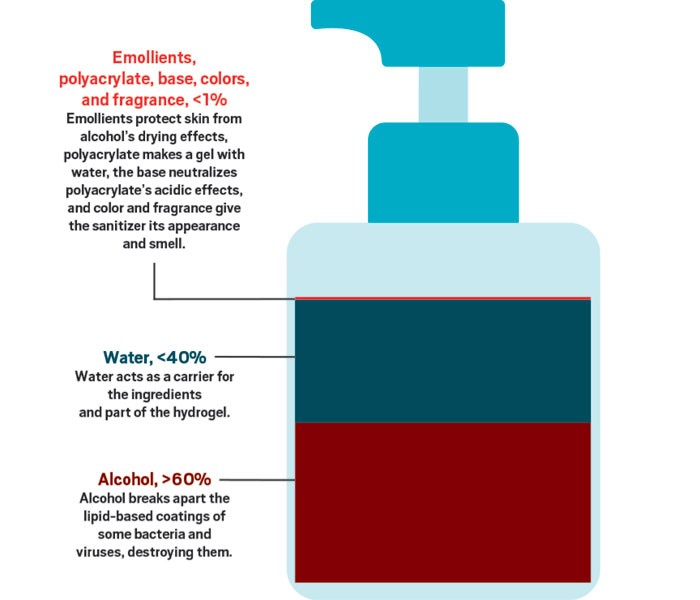

Although some hand sanitizers are sold without alcohol, it is the main ingredient in most products currently being snatched from store shelves. That’s because alcohol is a very effective disinfectant that is also safe to put on your skin. Alcohol’s job is to break up the outer coatings of bacteria and viruses.

SARS-CoV-2 is what’s known as an enveloped virus. Some viruses protect themselves with only a cage made of proteins. But as enveloped viruses leave cells they’ve infected, the viruses wrap themselves in a coat made of some of the cells’ lipid-based walls as well as some of their own proteins. According to chemist Pall Thordarson of the University of New South Wales, the lipid bilayers that surround enveloped viruses like SARS-CoV-2 are held together by a combination of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Like the lipids protecting these microorganisms, alcohols have a polar and a nonpolar region, so “ethanol and other alcohols disrupt these supramolecular interactions, effectively ‘dissolving’ the lipid membranes,” Thordarson says. However, he adds, you need a fairly high concentration of alcohol to rapidly break apart the organisms’ protective coating—which is why the CDC recommends using hand sanitizers with at least 60% alcohol.

But rubbing high concentrations of alcohol on your skin is not pleasant. The alcohol can quickly dry out your skin because it will also disrupt the protective layer of oils on your skin. That’s why hand sanitizers contain a moisturizer to counteract this drying.

The WHO offers two simple formulations for making your own hand-sanitizing liquids in resource-limited or remote areas where workers don’t have access to sinks or other hand-cleaning facilities. One of these formulations uses 80% ethanol, and the other, 75% isopropyl alcohol, otherwise known as rubbing alcohol. Both recipes contain a small amount of hydrogen peroxide to prevent microbes from growing in the sanitizer and a bit of glycerol to help moisturize skin and prevent dermatitis. Other moisturizing compounds you might find in liquid hand sanitizers include poly(ethylene glycol) and propylene glycol. When an alcohol-based hand sanitizer is rubbed into the skin, its ethanol evaporates, leaving behind these soothing compounds.

In clinics, runny, liquid hand sanitizers like those you can make from the WHO recipes are easily transferred to the hands of patients, doctors, and visitors from wall-mounted dispensers. For consumers, hand sanitizer gels are a lot easier to carry and dispense on the go because it’s easier to squeeze a gel from the bottle without spilling it everywhere. Gels also slow the evaporation of alcohol, ensuring it has time to cover your hands and work against the microbes that might be present.

People who have tried to make their own gel-based hand sanitizers can tell you that classic gelling agents like gelatin or agar won’t behave when mixed with the high concentrations of alcohol that you need to kill viruses and bacteria. These agents won’t form a gel that’s stable because polar alcohol groups interrupt the intermolecular bonds. Manufacturers get around this obstacle by using high-molecular-weight cross-linked polymers of acrylic acid. The covalent cross-links help make a viscous gel that’s resistant to alcohol’s disruption.

While most hand sanitizers contain either ethyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol, alcohol-free hand sanitizers are also for sale. These usually contain antimicrobial compounds like benzalkonium chloride that provide a lasting protection against bacteria. But alcohol-free products aren’t recommended by the CDC for fighting the novel coronavirus, because it isn’t yet clear that it can be used successfully against SARS-CoV-2.

So should you keep checking your local store religiously until alcohol-containing hand sanitizers are back in stock or buy up supplies if you see them? According to Rachel McCloy, an expert in behavioral science at the University of Reading, panic buying allows people to regain a feeling of control. But when people are scared, they often don’t make decisions that are rational or proportional to the risks. “It’s key to listen to experts in public health about the most effective actions that you can take at any point,” she says. And the best option is still washing your hands.

Soap and water are still the best option for hand hygiene, Thordarson emphasizes. Soap molecules not only disrupt noncovalent interactions that hold viruses and bacterial cell walls together but can also surround and help detach microbes from the skin. Hand sanitizers can’t remove microbes from the skin and aren’t effective against all germs. For example, noroviruses don't have a lipid membrane coating that can be broken up by alcohol, and the spores of Clostridium difficile have a tough coating of keratin that can protect them for years. Alcohol also doesn’t work as effectively when hands are dirty or greasy.

“Alcohol-based products work,” Thordarson says. “But nothing beats soap.”

CORRECTION

This story was updated on May 26, 2020, to clarify that the alcohol in hand sanitizers evaporates after being applied to skin. It does not dissolve.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter