Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Finance

Biotech fundraising in 2024: a story of haves and have-nots

Fewer firms are raising money. But those that can are getting record-breaking investment

by Rowan Walrath

April 17, 2024

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 102, Issue 12

If you’re a biotech start-up looking for funds in 2024, either you’re lucky enough to raise a nine-figure venture round, or you’re scrounging for what’s left over.

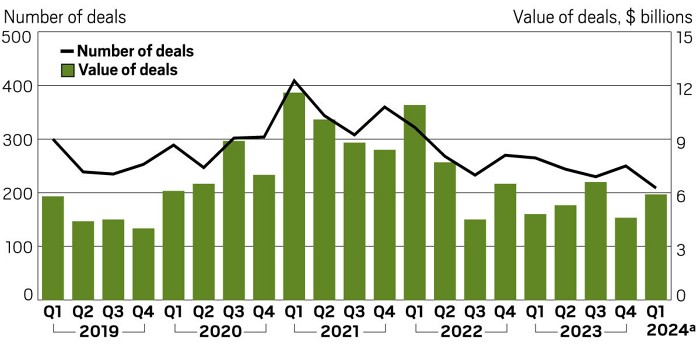

In the first quarter of this year, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies collectively raised $5.9 billion across 209 rounds, according to the latest Venture Monitor report from PitchBook and the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA). The dollar amount is an increase from the 2023 quarterly average, but it’s spread across fewer deals. The total deal count is the lowest since the third quarter of 2018, during which PitchBook recorded 202 venture rounds. Before that, only 2016 saw so few deals.

Sluggish start

The dip is especially low among early-stage deals. Industry watchers say investors are still risk averse and, consequently, prioritizing investment in companies whose drug candidates are farther along in development.

“I think the bar is still high,” says Katie McCarthy, chief innovation officer at the Halloran Consulting Group. “Investors have really reestablished their expectations. They do want to ensure there’s a reasonable amount of risk.”

Those start-ups that have managed to buck the trend and raise “mega-rounds”—$100 million or more—have a few things in common.

For one, investors are still likely to back experienced management teams. Chris Garabedian, portfolio manager at venture firm Perceptive Advisors and CEO of the accelerator Xontogeny, points to precision medicine start-up Mirador Therapeutics. Mirador launched in March with $400 million in venture capital. What made such a young start-up a sure bet for investors, Garabedian argues, are its founders: Mark McKenna and a few other executives from Prometheus Biosciences sold their last company to Merck & Co. for $10.8 billion.

“If you can bet on a proven team . . . well, instead of putting $4 million into 10 companies, let’s put $400 million into one,” Garabedian says. “If you put $4 million into 10 companies, you diversify the risk, but you also take on more management risk.”

Similarly, Synnovation Therapeutics, a cancer start-up that debuted with $102 million in January, is led by several former executives of Incyte who had launched multiple commercial drugs during their tenure there. FogPharma, which raised $145 million in March, was founded by chemist and serial entrepreneur Greg Verdine and is currently led by Johnson & Johnson veteran Mathai Mammen.

Investors are also more inclined to fund clinically validated science—that is, drug candidates that have been tested in humans. Cour Pharmaceuticals, which closed a $105 million round in January, has multiple Phase 2 studies in progress for its nanoparticle drugs, and Latigo Biotherapeutics’ lead drug candidate for pain relief was already in Phase 1 trials when the start-up launched with $135 million in February. Latigo’s compound LTG-001 works the same way a Vertex Pharmaceuticals drug does, giving investors extra confidence since the Vertex drug recently succeeded in a Phase 3 study.

Carolina Alarco, founder and principal of the consulting firm Bio Strategy Advisors and an angel investor, worries that this creates a secondary problem: that biotech may be “losing its edge” by deprioritizing newer programs.

“Experienced CEOs and founders normally gravitate toward proven technologies and platforms to have the most likelihood of success,” Alarco says. “Young entrepreneurs and scientists, they have the true innovation. They have the real treatments that are going to come out in 10 or 20 years. I think we’re doing a disservice to science by not opening up some funding to these highly innovative approaches.”

Still, there’s plenty of capital sitting on the sidelines—and investors can only wait so long to deploy it. Venture firms typically have to write checks within a certain period of time or return the money to their own investors.

Perceptive Advisors, Garabedian’s firm, has until May 2026 to spend a $515 million fund it closed in 2021. Several other venture capital firms are approaching similar cliffs: Many closed their last funds in 2020 and 2021, when the COVID-19 pandemic sparked new interest in biotechnology investment.

The same time pressure applies for pharmaceutical companies looking to acquire smaller firms or license their assets. Arda Ural, EY’s Americas industry markets leader for health sciences and wellness, says Big Pharma has about $1.2 trillion in capital available for mergers and acquisitions, down just slightly from the $1.37 trillion the sector had in December.

Meanwhile, the expiration of several major patents means some pharmaceutical companies are staring down billions of dollars in revenue loss over the next several years, Ural says. That could eventually outweigh the macroeconomic factors that create risk, including geopolitical tensions, high interest rates, and inflation.

It would be welcome news for the 30% of biotech startups that are looking for a flash sale because they have less than a year’s worth of cash runway.

“This cannot sustain in the long term,” Ural says. “Something’s got to give.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter