Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Start-ups

David Liu launches Beam Therapeutics to treat genetic diseases with CRISPR base editing

Joined by CRISPR luminaries Feng Zhang and J. Keith Joung, the Harvard chemist raises up to $87 million in funding

by Ryan Cross

May 14, 2018

When David R. Liu debuted his base editors, a modified form of CRISPR gene editing, two years ago, he recognized their potential to correct mutations underlying thousands of genetic conditions caused by typos in DNA.

Since then, those base editors, along with advanced iterations designed by Liu’s students at the Broad Institute of Harvard & MIT, have been shared with research labs worldwide more than 3,000 times. They’ve been used to edit DNA of bacteria, fungi, plants, insects, fish, amphibians, and mice. And in one controversial case, Chinese scientists even used Liu’s editors to fix a genetic disease in human embryos.

Amidst that whirlwind of development, Liu has been quietly building a company that will attempt to transform his base editing technique into therapies for numerous genetic diseases. Today, that start-up, Beam Therapeutics, is launching with up to $87 million in series A funding led by F-Prime Capital Partners and Arch Venture Partners.

Beam isn’t Liu’s first CRISPR company. Liu’s base editors are also the foundation of Pairwise Plants, which launched in March to develop gene-edited crops. He was also a cofounder of one of the original CRISPR companies, Editas Medicine, along with Feng Zhang, an inventor of CRISPR gene editing at the Broad, and J. Keith Joung, a gene editing researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

In fact, Zhang and Joung are joining Liu as cofounders of Beam too. “It was really a natural fit to keep the band together,” Liu says.

Editas, along with many other CRISPR companies, is largely focused on a traditional form of CRISPR gene editing that uses an enzyme called Cas9 to make specific cuts in DNA’s helical strands. Cas9, which Liu likens to a pair of molecular scissors, is useful for deleting and disrupting genes. It can also be used to create an opening for inserting a new stretch of DNA.

But the technique can’t swap a single base, or letter—A, T, G, or C—of DNA for another. Through a feat of protein engineering, Liu and his students created new versions of CRISPR—what they call base editors—that do just that.

Liu’s first base editor can convert C to T and G to A. His second model can convert A to G and T to C. According to one database, 33,000 single-letter DNA mutations are associated with disease. The four changes that Liu’s base editors can make could hypothetically correct 63% of them. “For some applications, scissors are the best tools,” Liu explains. “But if the goal is to simply fix a single-point mutation, base editing is really the best tool.”

In addition to licensing Liu’s base editors from Harvard, Beam may also license a base-editing system developed in Zhang’s lab called REPAIR that makes an A-to-G change in mRNA, the short-lived intermediate code between DNA and proteins. While Liu’s base editors are good for making permanent changes, REPAIR could be used as a transient treatment, because cells continually generate new mRNA.

Advertisement

Of course, many challenges lie ahead for turning any of these research tools into therapeutics. One of them is delivering the large base-editing complexes into cells affected by a disease. John Evans, Beam’s CEO and a former executive at Agios, thinks Beam will benefit from the progress that other groups developing CRISPR therapies have made in the past four years. “I think the foundation that’s been laid by other companies in this field will really help us go faster,” he says.

Beam isn’t disclosing what diseases it hopes to treat, but Liu says the company has already launched 10 to 15 programs exploring different targets. Base editing could allow it to more easily tackle diseases that other companies are already working on with Cas9-based gene editing.

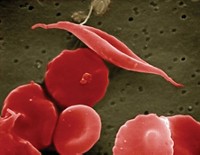

For instance, sickle cell disease is caused by a single DNA typo in a gene for adult hemoglobin. Other companies are already attempting to treat sickle cell, not by fixing this typo but by using CRISPR to turn on the production of a normally repressed form of fetal hemoglobin to make up for the mutant adult hemoglobin. Base editing could offer a more straightforward approach to treating the disease by fixing the mutation in adult hemoglobin.

“We obviously have the resources in hand to do many things in parallel,” Evans says. “So you can expect a very broad pipeline from us.”

Beam has 15 employees now, including Giuseppe Ciaramella, who left his position as chief scientific officer of Moderna Therapeutics’ vaccine division in March. Ciaramella will direct Beam’s research.

Several former students from the cofounders’ labs are at Beam as well. “That is a testament to the passion that we all feel for these technologies,” Liu says. “We want to make sure the science actually ends up benefiting society in a broad and meaningful way.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter