Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Diversity

Science in the US is built on immigrants. Will they keep coming?

International scientists have long been a key part of the US research workforce, but concerns are rising that they’ll start to turn elsewhere

by Andrea Widener

March 4, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 9

Credit: Davide Bonazzi

In brief

Immigration is a huge contributor to US science and innovation, with thousands of students and scholars coming to the country each year. But the increase in anti-immigrant rhetoric in the past few years has scientists worried that their international colleagues might choose to go to other countries instead. So far, though, few changes to immigration policy are preventing scientists from studying and working in the US. Read on to hear the stories of immigrant chemists and find out more about the challenges they face.

Almost as soon as he started college, Morteza Khaledi knew he wanted to be a professor. And he quickly decided that a doctoral degree from a US university was the best path to get there.

Armed with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Pahlavi University (now Shiraz University), in Iran, Khaledi applied to several US universities for graduate school. He was accepted to the University of Florida in 1978, and he has lived in the US ever since. Over those four decades, he rose from student to chemistry professor to, now, dean of science at the University of Texas at Arlington.

“When I was a student, the US was really dominant in science and technology areas, and I think we still have the upper hand,” he says. “But other countries have caught up.”

He worries that increased competition, amplified by the current wave of anti-immigrant rhetoric in the US, will push top international students to choose schools in Canada, Europe, Singapore, and elsewhere. “There are great talents from all over the world,” Khaledi says. “If you close the door or limit them, then it will have an impact on the research that we do.”

Much of the rest of the scientific community is worried too. With constant talk of a border wall, trade fights with China, and sanctions against Russia, immigration is at the top of many scientists’ minds worldwide.

The Donald J. Trump administration has made some changes to immigration policy. The most notable is the ban against immigrants from six countries, including Iran. Other proposals include stricter examination of Chinese students and scientific visitors, changes to the H-1B visa system for temporary workers, and work restrictions on the spouses of US visa holders.

Despite those changes, though, most scientists are still able to come to the US as they could before Trump became president, albeit with the potential for longer waits. Big changes to US immigration policy—including talk of moving to an immigration system that prioritizes highly skilled workers—will require an act of Congress, something unlikely to happen given the wide political divides.

But words have power, and the negative political talk about immigration appears to be having an effect: the number of international applicants to study at US colleges and universities has declined two years in a row. And more and more scientists are starting to question whether the US is the right place for them.

“Every meeting we go to abroad, someone will express concern about US visa issues and visa policy. Every single meeting,” says Kathie Bailey, director of the Board on International Scientific Organizations at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “Perceptions are very difficult to battle.”

Scientist immigration by the numbers

-

34.5

Percentage of doctoral-degree chemists who were naturalized or non-US citizens in 2017a

-

53.1

Percentage of doctoral-degree chemical engineers who were naturalized or non-US citizens in 2017a

-

75.6

Percentage of foreign-born recipients of US science and engineering doctoral degrees in 2015 who planned to stay in the USb

-

24

Percentage of US patents with at least one non-US citizen inventor in 2007c

-

2008

Year the number of immigrants from Asia to the US overtook immigration from Latin Americad

-

78

Percentage of US adults who believe the country should encourage immigration of high-skilled workerse

Impact of science immigration

Chemist Hye-Won Song felt limited by the research choices in her native South Korea. So after she finished a master’s degree there, she applied to graduate schools in the US. “There are more opportunities and more research topics going on,” she says.

That same wide range of research opportunities led her to want to stay in the US after getting her doctoral degree at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California San Diego. But staying wasn’t easy.

Song spent five years in her postdoc, in part waiting for her research papers and citations to stack up while she looked for a job. She was also saving money to hire a lawyer to take her through the immigration process.

In the meantime, she had to deal with the constant uncertainty of being in the US on a limited visa. Once Song had to file a duplicate renewal application—and miss a paycheck—when her original paperwork got lost in the system. And every time she got a new visa, she also had to visit the Department of Motor Vehicles to renew her driver’s license. “It really makes our lives miserable, but most people don’t know about it,” Song says.

Eventually, Song succeeded in becoming a permanent US resident, with the green card to prove it. That status made it a lot easier for her to find a job in industry. “A lot of companies, they do not offer to support a visa,” she says. “They want you to bring your green card with you.”

Song’s story is familiar to many scientists who immigrate to the US and stay. They face constant uncertainty with each visa renewal, along with fear that a visit home might mean they can’t return to work. But they keep coming because of the science. “Research-wise it was worth getting here,” Song says.

The domestic US research community, too, thinks it is worth including foreign-born scientists and for the most part has welcomed immigrants into labs with open arms. “Immigration has been a tremendous boost to science and engineering,” says Harvard Business School’s William Kerr, who has written a book on immigration, The Gift of Global Talent.

Almost any way you look at it—percentages of patents, Nobel Prize winners, citations, entrepreneurs—immigrants match or exceed native US workers, he says. Currently, immigrants make up around 25% of all US science and technology workers and around 50% of the doctoral-level science workforce nationwide.

Kerr’s work and that of others has found that for the most part, international scientists don’t compete with domestic researchers. “You don’t have a fixed pie of jobs,” he explains. Immigrants “make the pie bigger, adding on to what natives would have accomplished.”

Immigrants to the US are more likely than native scientists to be self-employed, including as entrepreneurs, says Jennifer Hunt, an economist at Rutgers University. Immigrants are also more likely to hold patents. “More people means more ideas and probably more innovation,” Hunt explains.

Mikhail Shapiro, a California Institute of Technology chemical engineering professor, came to the US from Russia when he was 11. While he doesn’t think his immigrant background changed his career path, he does think it gave him a certain mentality. “There is a desire to seize opportunities and work hard and really make the most of the opportunities you have,” he says.

That has also been the experience of Jeremy Levin, chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics. Levin lived in South Africa and then Rhodesia before getting his degrees and working in the UK. He then moved to the US specifically because of its vibrant science and innovation culture. He commonly sees other immigrants at the head of science and technology companies, and research labs filled with immigrants.

Immigration “has been a critical component not just of driving innovation but sustaining the US economy in a way that is just remarkable,” Levin says.

Levin worries that any tightening of US immigration policy—perceived or real—will have long-term consequences for the US economy, especially in the biological sciences. In 2017, he wrote a letter in Nature Biotechnology signed by over 150 biotech leaders and founders against Trump’s ban on select immigrants.

The political rhetoric around immigrant criminals and the need for a wall on the US-Mexico border is “raising the specter of intolerance, raising the specter of racism,” he says. “All of this is designed to raise fears around immigration.”

Terrorism is a real threat that must be addressed, Levin believes. He speaks from personal experience here, too: he was once inspecting a pharmaceutical plant in Israel as it was bombed by Hamas, a militant group. But the fight against terrorism “needs to be distinguished from the need to attract incredibly bright people who want to contribute to science,” he says.

“Many of the best scientists in Europe and Asia will choose not to come to us,” Levin says. “They perceive that the barriers to entry in the US have been raised unreasonably high.”

Typical US visa types for chemists

-

F-1

A temporary visa issued to most international students who are accepted to a US college or university as an undergraduate or graduate. Students must prove they can pay tuition or that it is covered in other ways.

-

OPT

Short for optional practical training, an extension of the F-1 visa, for scientists, that can last up to three years. Frequently used to begin postdoctoral training or start a job while applying for another visa.

-

J-1

A temporary visa issued to research scholars and other visitors. Commonly used by postdoctoral scholars.

-

H-1B

A temporary visa for which employers apply to bring in specific high-skilled workers unavailable domestically. The number of visas is capped for companies but unlimited for nonprofit organizations, including universities.

-

E-2

Permanent resident status, signified by obtaining a so-called green card. Requires applicants to submit paperwork proving their value, such as by listing papers published or documenting community service, such as peer review. Frequently requires a job offer from a US organization.

Scaring off students

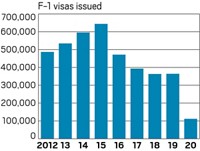

Regardless of whether the US is actually harder to enter, there has been a measurable decline in international students applying to come to the US. The number of applications from international graduate students to study in the US has dropped a total of 4% in the last two years across all fields. That average masks a more significant 9% decline in physical and earth sciences from 2017 to 2018, according to data from the Council of Graduate Schools.

Academic and industrial scientists worry whether that trend will continue and whether it will spread beyond students. The chaotic rollout of Trump’s travel ban in January 2017 “really spooked international students and scholars,” says Rachel Banks, director of public policy at NAFSA: Association of International Educators. “People increasingly started thinking twice.”

When people are deciding where to go to college or graduate school, they are thinking ahead to whether it’s a place they want to be long term. People who start their education in another country are less likely to migrate to the US later. “You have to think about the international student experience like a pipeline,” Banks says. As international student enrollment has dropped in the US, it has gone up in Australia, Canada, China, and elsewhere. “No doubt they have taken advantage of what is happening in the US as a marketing tool,” Banks says.

Shapiro from Caltech has seen the impact of stricter policies among his students. Currently he has a doctoral student who has been stuck in China for months because he can’t get his visa renewed. “It’s not fair to them,” he says. He hopes the current atmosphere is temporary. “I don’t care where they come from. I want them to stay here.”

Currently, China sends more students to study in the US than any other country. At the same time, the Trump administration has proposed changes, including more scrutiny on scientists working on robotics, aviation, and high-tech manufacturing, that specifically target Chinese immigrants because of fears they are appropriating those technologies. Chemistry has escaped the spotlight so far.

Any moves that significantly shut down Chinese student immigration could be devastating, Harvard’s Kerr says. Currently, about 9% of US innovation is attributed to scientists of Chinese ethnicity.

Advertisement

“It would send shock waves through the system,” Kerr says. “Nothing we have done up until now would compare to revoking student visas.”

That impact would be felt especially hard in chemistry. Economist Patrick Gaule from the University of Bath has studied the quality of chemistry graduate students from China.

His 2013 study of 16,000 US chemistry PhDs showed that Chinese students in chemistry publish more than average. Their quality—as measured by those publications—equals that of domestic students who receive National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships (Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, DOI: 10.1162/rest_a_00283). “It’s more difficult to get into a PhD program if you are applying from China than applying from inside the US,” he says. “That’s what I think is driving the results.”

Gaule has also surveyed US chemistry graduate students on their future-employment preferences. He continues to find that students want to stay in the US. People worry that “everybody is going to Canada,” he says. “So far we don’t see it.”

That’s been the case for postdocs as well. Of approximately 80,000 postdocs in the US, two-thirds are international scholars, says Tracy Costello, chair of the board of directors at the National Postdoctoral Association and director of postdoctoral affairs at the Moffitt Cancer Center.

“We want to foster an environment where if someone comes and trains here and wants to stay, that’s possible,” Costello says. “If they want to take that knowledge and go back to their countries, that’s possible too. Science is a global enterprise.”

While the postdoc association is concerned about the immigration-related rhetoric, “We hear the sky is falling a lot and somehow there is still a sky,” she says. Fundamentally, the system hasn’t changed, and while she expects minor changes from the Trump administration, “the status quo for right now is not a bad space.”

In 2009, after finishing graduate school in China, Zuolei Liao came to the US as a postdoc, attracted both by the research and by the culture. He works in uranium chemistry and so expected to have to wait a long time for his visa, but it came through in a few weeks, and he was soon on his way to the University of Notre Dame.

Liao spent several years there and then at Oregon State University, first on a visitor visa and then on an H-1B. After several years, he decided he wanted to stay in the US. But he didn’t take a traditional path: Liao joined the military, which made him eligible for citizenship at the end of basic training.

“I probably would have still joined if I had the chance,” even without the opportunity for citizenship, he says. “I just wanted to get more experience, to make myself a better person.”

After 4½ years in the army, Liao now works at a pharmaceutical company in Wisconsin. He knows only a few other scientists who also turned to military service to stay in the country—but however it’s accomplished, he thinks the US should encourage more doctoral students and postdocs to stay. “We trained them here, so we shouldn’t send them to other countries,” he says. “If you follow the law, you should be rewarded.”

Enduring employment woes

“What Trump has done more than anything is just make people scared,” says Brian Getson, an attorney at immigration specialty law firm Getson & Schatz.

While the Trump administration hasn’t eased immigration to the US, at the same time, “there is no proposal to make it more difficult for scientists,” adds Marco Pignone, who is also an attorney at Getson & Schatz and often represents chemists.

Part of the firm’s job is to reassure people that they can still get an employment visa or green card, Getson says. Visa delays have increased, however, especially for scientists from India and China, Getson says. There are more people who want green cards from those countries than the number available.

One of the main ways scientists come to the US for work or stay after graduation is through employer-sponsored visas. Currently, only 25% of US visas are driven by employment (the remaining 75% are family based).

The H-1B, a temporary visa for high-skilled workers, is sometimes the first step. Nonprofits, including universities, don’t have a limit on H-1B slots. But companies do have a limit. There are 85,000 slots available, and companies nationwide routinely submit double that many applications within days of the application system opening each year. Visa recipients are then chosen by lottery.

A lottery is “probably not the best way,” Kerr points out. Even large companies that apply for thousands of H-1Bs don’t get to choose which workers get the visa slots, which means they often aren’t getting their top choice among their applicants.

Right now, around 70% of H-1B visas go to jobs in the computer and technology industry, while just 2.6% fill positions in mathematics and physical sciences.

The Trump administration has proposed some changes to H-1Bs. One would give people with master’s degrees and higher a better chance of getting a slot.

Another would switch the H-1B application process from paper to electronic. “I imagine it would require a lot of money, but it would be money well spent,” Rutgers’s Hunt says. An electronic system would make it easier to tweak the H-1B lottery so it is not as random. And it could allow for better representation across fields rather than letting computer-science occupations crowd out other sectors.

Kerr likes the idea of giving priority to the jobs with the highest salaries, which generally indicate that a job is harder to fill. Some economists have also proposed giving greater preference to applicants with the highest degrees.

“High-skilled immigration is fundamentally an investment,” Kerr says.

But as clunky as the US immigration system is, immigrants in the US tend to have better employment outcomes than those in other countries, and that may be because in the US, more are being chosen by companies than by the government, Hunt says. “I’m actually not sure that the current system is terrible,” Hunt says.

An immigrant from Germany, Jens Breffke went through “the whole alphabet of visas” on his road to becoming a citizen.

Looking for an international adventure, Breffke came to the US on a student F-1 visa to attend graduate school, then began a postdoc at the National Institute of Standards and Technology using a three-year F-1 extension for scientists called OPT for optional practical training.

But when it came time to look for a job in industry, Breffke felt stuck. He couldn’t easily transition to an industry-sponsored H-1B because visa rules meant a gap of almost a year and a half between the time his postdoc ended and when he would have been eligible for an H-1B—and then he still would’ve been subject to the lottery.

“You have to find someone who wants to hire you so badly a year and a half in advance,” Breffke says. “Even if you are the most qualified person, you will always be second in line to someone who could just be hired this week.”

Breffke thinks he would have eventually qualified for a visa for exceptional scientists, but it takes years for the publications and citations that count toward that “exceptional” grade to accumulate. In the end, his girlfriend proposed, and he got a visa through his marriage. He now works for an electronics company in Boston and also serves as chair of the International Activities Committee for the American Chemical Society, which publishes C&EN.

“I did my PhD in this country and a postdoc working for Uncle Sam,” he says. “I do believe I deserved a chance to work in this country, but the system makes that pretty much impossible.”

Changing the climate

“Immigration writ large is top of mind for a lot of people,” says Susan Butts, a consultant and former senior director at Dow Chemical who is chairing an ACS committee developing a policy statement on immigration.

This isn’t the first time the society has tried to develop a policy on the issue, Butts says. The previous effort “was unsuccessful because they could not come to a consensus,” she says. She’s hoping for a different outcome this time. The group has looked at data on immigration, as well as examined surveys of ACS members on the issue.

While there are individual ACS members who are worried about losing their jobs to immigrants, Butts says, “there are a lot of data that say immigrants are an important part of the chemistry enterprise, especially at the advanced-degree level.”

If things go smoothly, a policy statement could be out by the end of 2019, Butts says. Having the statement will enable ACS to better engage in immigration policy discussions in Washington, DC, as part of ACS’s mission to support the chemical enterprise.

Major changes to US immigration policy aren’t likely soon, given the massive divide between Democrats and Republicans in Congress. Many advocates for immigration reform in the past have left Congress, and it’s unclear now who will push for reform.

Kerr says that the US has never had an easy immigration system, and people would adjust if any changes are made fairly for all immigrants.

But denying entry to specific groups can cause serious repercussions. The outcome of recent discourse “really has been to fundamentally shake the confidence that people all around the world have in the United States and whether the US is where they want to make their long-term investment,” Kerr says. “We are getting a black eye.”

That concerning atmosphere isn’t just for scientists abroad. Chemist Madan Bhasin immigrated to the US from India in 1959 and eventually got his PhD at Notre Dame. He got a job at Union Carbide in West Virginia in 1963 and has lived in the area ever since.

Just a handful of Indian families were in the area when Bhasin and his wife first arrived. Although he initially heard some talk about foreigners taking away jobs from US workers, anti-immigrant sentiment in the wider community hadn’t been prevalent until recently.

“I’m fortunate to have come here and to be very happy here,” Bhasin says. But he has felt a difference in the atmosphere in the last few years. To be cautious, his local Indian community center hired police to patrol a function after hearing about attacks on immigrants nationwide. His grandson warned him to be careful in the community.

Bhasin hopes that anti-immigrant rhetoric and visa challenges won’t keep scientists away, but he has heard horror stories from some of his scientist friends who visited India on vacation and then had trouble returning. Trying to immigrate “has been a nightmare for some of them,” he says. “Many people are not even considering coming.”

“I wish we could all practice tolerance toward each other,” Bhasin says.

Anti-immigrant sentiment is what prompted Khaledi from UT Arlington to finally get his green card. “The motivating factor was that after 9/11, things got serious,” he says, referring to the 2001 terrorist attack in the US.

One of his students, from Vietnam, was particularly concerned that Khaledi would go to an international conference and never be able to return. “He used to bring citizenship forms, and he would fill out what he could and sit them on my desk,” Khaledi says.

Khaledi knows that many students are considering the challenges versus benefits of staying in the US or going elsewhere. He remembers a particular Iranian student who was top notch, with perfect English and a stellar record, who ended up going to another country because she couldn’t get a US visa. “You want these people to come here,” he says.

“I don’t see what we gain by excluding people. We’re talking about scientists; we are not talking about politicians. You remove the politics from it, and we all benefit.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter