Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

Cora Young

Pollutant detective is tracking trace chemicals that affect climate and air quality

by Katherine Bourzac

August 25, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 33

Credit: Courtesy of Cora Young/Atmos. Chem. Phys./C&EN

If you need to borrow a wrench—any size, imperial or metric—stop by Cora Young’s office at York University. She’s got a full set on hand for repairs in the lab or to get her analytical instruments ready for a trip to the Arctic or a bumpy airplane ride through clouds of wildfire smoke.

And if you need observational data about a persistent pollutant or trace atmospheric chemical, Young is also the perfect person to ask. She applies her analytical flair to a wide variety of problems in atmospheric chemistry.

Young’s specialty is combining challenging field measurements with finicky precision lab techniques, such as liquid chromatography. That expertise has expanded chemists’ understanding of a broad range of pollutants that are present in the environment at low concentrations but can have outsize effects on urban air quality or the Arctic environment.

“I look for where measuring trace compounds can make a difference,” she says.

Young is “one of the world’s leading experts on persistent organic pollutants,” says Steven Brown, who was her postdoc adviser at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colorado. These chemicals, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), stick around in the environment for years or decades without getting broken down. The pollutants can accumulate in ecosystems, the water supply, and the air and can travel even to the remotest Arctic landscapes.

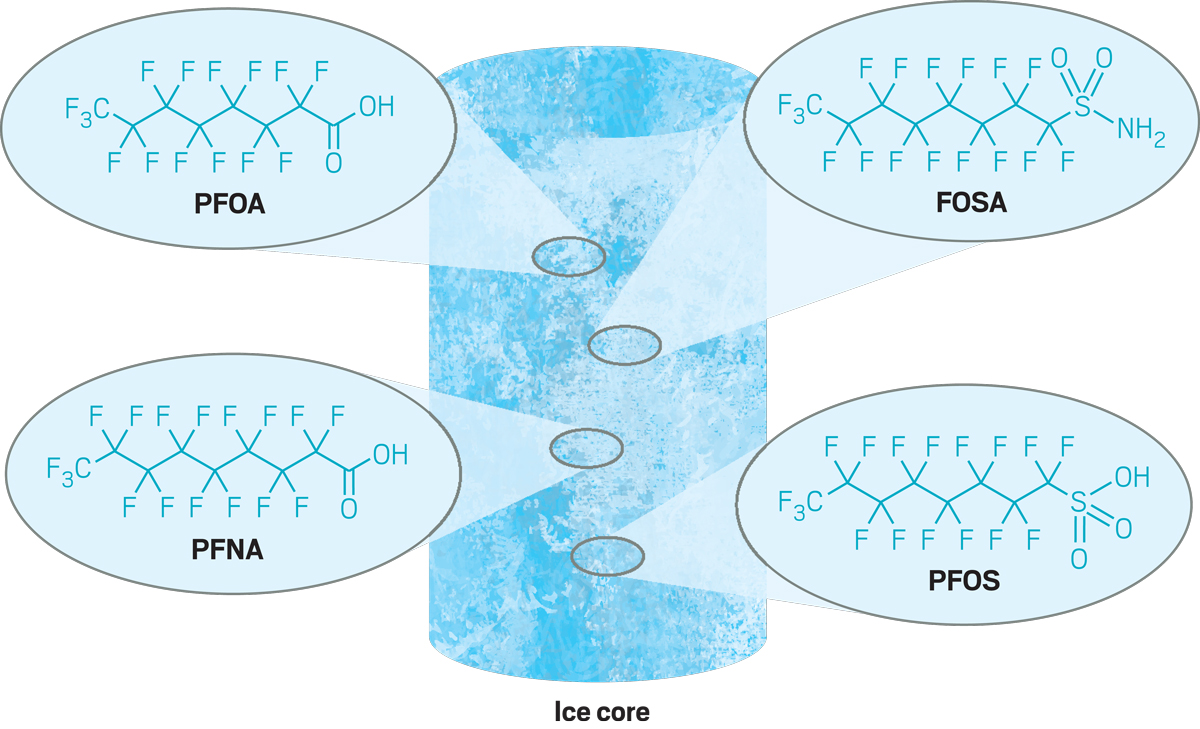

In 2018, Young found evidence of perfluoroalkyl acids, which are chemicals in the PFAS category, in a core drilled from the Devon Ice Cap in Nunavut, Canada. Glaciologists collected the ice cores, but there weren’t established methods for studying their PFAS content. Young brought her analytical expertise to the problem.

The results were surprising. “Because these are really strong acids, you’d think they’d get deposited really close to where they are used,” she says. But the compounds clearly travel—and with alarming ease. In spite of bans on some of them in many countries, their accumulation in the Arctic has been increasing since the 1970s. Young is now studying an ice core from the 1960s in work that she hopes will provide more insights into these persistent pollutants.

Yet PFAS are just one of Young’s specialties, Brown says. “The breadth of topics she’s worked on is impressive.” NOAA has adopted some of her methods, including one for measuring the urban pollutant nitrogen dioxide, as standard measurements.

While she’s got plenty on her plate, Young says she continues to keep her eyes open for environmental problems whose scope is unclear because of a lack of data. She’s studying how chloride in the atmosphere becomes reactive, sending instruments and students to study the chemistry of wildfire smoke, and developing analytical standards for studying indoor air quality.

What unites all these projects, she says, is having her interest piqued by some important environmental problem, then realizing, “Oh, I have a measurement that might fill a gap there.”

Advertisement

If you need to borrow a wrench—any size, imperial or metric—stop by Cora Young’s office at York University. She’s got a full set on hand for repairs in the lab or to get her analytical instruments ready for a trip to the Arctic or a bumpy airplane ride through clouds of wildfire smoke.

And if you need observational data about a persistent pollutant or trace atmospheric chemical, Young is also the perfect person to ask. She applies her analytical flair to a wide variety of problems in atmospheric chemistry.

Advertisement

Young’s specialty is combining challenging field measurements with finicky precision lab techniques, such as liquid chromatography. That expertise has expanded chemists’ understanding of a broad range of pollutants that are present in the environment at low concentrations but can have outsize effects on urban air quality or the Arctic environment.

“I look for where measuring trace compounds can make a difference,” she says.

Young is “one of the world’s leading experts on persistent organic pollutants,” says Steven Brown, who was her postdoc adviser at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colorado. These chemicals, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), stick around in the environment for years or decades without getting broken down. The pollutants can accumulate in ecosystems, the water supply, and the air and can travel even to the remotest Arctic landscapes.

In 2018, Young found evidence of perfluoroalkyl acids, which are chemicals in the PFAS category, in a core drilled from the Devon Ice Cap in Nunavut, Canada. Glaciologists collected the ice cores, but there weren’t established methods for studying their PFAS content. Young brought her analytical expertise to the problem.

The results were surprising. “Because these are really strong acids, you’d think they’d get deposited really close to where they are used,” she says. But the compounds clearly travel—and with alarming ease. In spite of bans on some of them in many countries, their accumulation in the Arctic has been increasing since the 1970s. Young is now studying an ice core from the 1960s in work that she hopes will provide more insights into these persistent pollutants.

Yet PFAS are just one of Young’s specialties, Brown says. “The breadth of topics she’s worked on is impressive.” NOAA has adopted some of her methods, including one for measuring the urban pollutant nitrogen dioxide, as standard measurements.

While she’s got plenty on her plate, Young says she continues to keep her eyes open for environmental problems whose scope is unclear because of a lack of data. She’s studying how chloride in the atmosphere becomes reactive, sending instruments and students to study the chemistry of wildfire smoke, and developing analytical standards for studying indoor air quality.

What unites all these projects, she says, is having her interest piqued by some important environmental problem, then realizing, “Oh, I have a measurement that might fill a gap there.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: York University

Age: 38

PhD alma mater: University of Toronto

If I weren’t a chemist, I would be: “An urban planner. My alternate universe involves lots of public transit and bike lanes.”

I’ve overcome adversity in the lab by: “Collecting samples in the environment provides plenty of challenges, including samplers blowing over in hurricane-force winds, animals chewing on or knocking over instrumentation, finding dead animals inside the samplers, fixing instrumentation in a swarm of blackflies, and extremely unglamorous bathroom options.”

Must-have in the lab: “A full set of wrenches (both imperial and metric).”

Must-have on the road: “Travel-sized tea kettle. I need tea to function, and I hate it when my tea tastes like coffee!”

Research at a glance

Credit: Yang H. Ku/C&EN

Young studies ice cores collected in the Canadian Arctic to analyze their levels of persistent organic pollutants called PFAS, which she's found are on the rise in the region.

Three key papers

“Continuous Non-marine Inputs of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances to the High Arctic: A Multi-decadal Temporal Record”

(Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, DOI: 10.5194/acp-18-5045-2018)

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter