Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

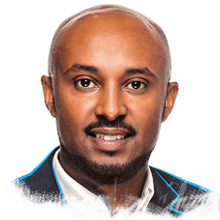

Marina Evich

This environmental chemist finds new ways to track down contaminants in soil and water

by Leigh Krietsch Boerner

May 19, 2023

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 101, Issue 16

Credit: Charlie Dean/Will Ludwig/C&EN | Marina Evich

s a chemist at the US Environmental Protection Agency, Marina Evich susses out contaminants in the environment. Sound straightforward? It’s not. Most of the time, Evich doesn’t know exactly which compounds she’s looking for. Natural environments host incredibly complex chemical mixtures, she says, and various analytical techniques can detect specific, known compounds in this soup. But these targeted methods can miss unexpected molecules that contribute to the overall burden of pollution. To find these unknowns, Evich uses nontargeted analysis—instead of directly detecting a chemical, she examines what effects it has on an ecosystem.

One approach involves using fish as tiny swimming canaries that sing a warning song through their metabolites. When Evich was a postdoctoral scholar at the EPA, her colleagues put lab-raised fish into a water source and let them swim around for a set period of time. Then Evich looked at the metabolites the fish built up in their bodies and compared the compounds with those in control fish who stayed in tanks in the lab.

“If the metabolomic profiles were similar to the control fish, then we would say, ‘OK, maybe this river or stream was not a priority for us,’ ” she says. “And if they were very vastly different, then we would say, ‘This stream has something that’s impacting the metabolomic profiles and the different pathways in the fish.’ ” Combining these data with information about the fish’s metabolic pathways could then reveal the identities of the contaminants.

After completing her postdoc in 2020, Evich remained at the EPA to study the fate and transport of pollutants, using pollutant modeling and mass spectrometry to understand what happens to these chemicals when they enter the environment. She focuses mostly on toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), sometimes called forever chemicals, and how they change in soils.

“I think it’s our duty to leave the environment in a better state for future generations.”

—Marina Evich, chemist, US Environmental Protection Agency

Most human exposure to PFAS is through drinking water, and this kind of contamination is relatively easy to clean up once it has been identified. But when the contaminants get into soil, things are more complicated. The soil acts as a PFAS reservoir that slowly releases contaminants into nearby water systems, Evich says. This process is challenging to study, in part because there are thousands of PFAS, and scientists don’t know much about many of them. But if researchers like Evich can understand more about how the pollutants behave in soils, they can develop strategies to prevent these compounds from polluting waterways.

Evich has tentatively identified previously unknown PFAS contaminants at low concentrations in soils, and her work is having a big impact on the scientific understanding of organic contaminants, says John Washington, a chemist who works with Evich at the EPA. “She is willing and able to delve into disciplines that are new to her and become proficient in short order.”

Although she grew up in Atlanta, Evich was born in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, a town near the northeastern tip of the Black Sea. Her family came to the US in 1989, fleeing religious persecution and political unrest shortly before the breakup of the Soviet Union. She earned her graduate degree in biophysical chemistry from Georgia State University, where she studied interactions between biological molecules. “I got my PhD mostly in DNA structure and DNA damage,” she says. “It’s interesting because it’s not environmental science at all, which is where my career ended up.”

After graduate school, Evich’s postdoctoral work using fish got her interested in developing other ways to detect unknown compounds in the environment and fired her determination to prevent pollution and ecological damage. “My love of the environment is due to my parents, who were always pushing me to spend every moment outside,” she says. Evich spent her childhood playing in lakes and streams and fishing with her dad. It’s heartbreaking that pollution might deprive children of similar experiences, she says. “I think it’s our duty to leave the environment in a better state for future generations.”

Vitals

Current affiliation:

US Environmental Protection Agency

Age: 35

PhD alma mater:

Georgia State University

Hometown:

Rostov-on-Don, Russia, and Atlanta

How I’ve faced adversity in my career:

“Like many young scientists, I’ve struggled with impostor syndrome. While research can be incredibly fulfilling, failures and manuscript rejections are inevitable, and these things can contribute to feelings of self-doubt. I think it’s important to not let failures or even successes define happiness and self-worth.”

My favorite TV show is:

“Seinfeld. It’s one of those TV shows I grew up watching and can still watch decades later.”

Learn more/nominate a rising early-career chemist to be one of C&EN's Talented 12 at:

cenm.ag/t12-nominations-2024

As a chemist at the US Environmental Protection Agency, Marina Evich susses out contaminants in the environment. Sound straightforward? It’s not. Most of the time, Evich doesn’t know exactly which compounds she’s looking for. Natural environments host incredibly complex chemical mixtures, she says, and various analytical techniques can detect specific, known compounds in this soup. But these targeted methods can miss unexpected molecules that contribute to the overall burden of pollution. To find these unknowns, Evich uses nontargeted analysis—instead of directly detecting a chemical, she examines what effects it has on an ecosystem.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: US Environmental Protection Agency

▸ Age: 35

▸ PhD alma mater: Georgia State University

▸ Hometown: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, and Atlanta

▸ How I’ve faced adversity in my career: “Like many young scientists, I’ve struggled with impostor syndrome. While research can be incredibly fulfilling, failures and manuscript rejections are inevitable, and these things can contribute to feelings of self-doubt. I think it’s important to not let failures or even successes define happiness and self-worth.”

▸ My favorite TV show is: “Seinfeld. It’s one of those TV shows I grew up watching and can still watch decades later.”

One approach involves using fish as tiny swimming canaries that sing a warning song through their metabolites. When Evich was a postdoctoral scholar at the EPA, her colleagues put lab-raised fish into a water source and let them swim around for a set period of time. Then Evich looked at the metabolites the fish built up in their bodies and compared the compounds with those in control fish who stayed in tanks in the lab.

“If the metabolomic profiles were similar to the control fish, then we would say, ‘OK, maybe this river or stream was not a priority for us,’ ” she says. “And if they were very vastly different, then we would say, ‘This stream has something that’s impacting the metabolomic profiles and the different pathways in the fish.’ ” Combining these data with information about the fish’s metabolic pathways could then reveal the identities of the contaminants.

After completing her postdoc in 2020, Evich remained at the EPA to study the fate and transport of pollutants, using pollutant modeling and mass spectrometry to understand what happens to these chemicals when they enter the environment. She focuses mostly on toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), sometimes called forever chemicals, and how they change in soils.

Most human exposure to PFAS is through drinking water, and this kind of contamination is relatively easy to clean up once it has been identified. But when the contaminants get into soil, things are more complicated. The soil acts as a PFAS reservoir that slowly releases contaminants into nearby water systems, Evich says. This process is challenging to study, in part because there are thousands of PFAS, and scientists don’t know much about many of them. But if researchers like Evich can understand more about how the pollutants behave in soils, they can develop strategies to prevent these compounds from polluting waterways.

Evich has tentatively identified previously unknown PFAS contaminants at low concentrations in soils, and her work is having a big impact on the scientific understanding of organic contaminants, says John Washington, a chemist who works with Evich at the EPA. “She is willing and able to delve into disciplines that are new to her and become proficient in short order.”

Although she grew up in Atlanta, Evich was born in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, a town near the northeastern tip of the Black Sea. Her family came to the US in 1989, fleeing religious persecution and political unrest shortly before the breakup of the Soviet Union. She earned her graduate degree in biophysical chemistry from Georgia State University, where she studied interactions between biological molecules. “I got my PhD mostly in DNA structure and DNA damage,” she says. “It’s interesting because it’s not environmental science at all, which is where my career ended up.”

After graduate school, Evich’s postdoctoral work using fish got her interested in developing other ways to detect unknown compounds in the environment and fired her determination to prevent pollution and ecological damage. “My love of the environment is due to my parents, who were always pushing me to spend every moment outside,” she says. Evich spent her childhood playing in lakes and streams and fishing with her dad. It’s heartbreaking that pollution might deprive children of similar experiences, she says. “I think it’s our duty to leave the environment in a better state for future generations.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter