Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Sustainability

Can laboratories move away from single-use plastic?

Finding alternatives to single-use plastic won’t be easy for scientists, but here are some of the ways that they are starting to change their habits

by Laura Howes

November 3, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 43

In September, PhD student Samantha Seah challenged herself to collect all the plastic and nitrile waste she used in her lab in one day. Pipette tips, tubes, gloves, they quickly added up. At the end of her working day, Seah, who studies droplet microfluidics at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, weighed the waste. It totaled 230 g. In a year, she estimates, that would add up to about 60 kg, or the weight of a small person.

Seah wasn’t the first to try to measure how much plastic gets tossed in the trash in labs. In 2015, a team at the University of Exeter did a back-of-the-envelope calculation to estimate how much plastic waste scientific labs generate in a year. The answer was over 5.5 million metric tons (Nature 2015, DOI: 10.1038/528479c). The researchers based their estimate on extrapolations from their biosciences department. More accurate numbers for how much scientific research contributes to global consumption of single-use plastic do not seem to exist.

Seah’s efforts were part of a social media campaign started by a group of young researchers who worked with the publisher eLife Sciences Publications. The campaign aimed to show how much single-use plastic was being used by scientists across the world. In #LabWasteDay posts on Twitter, the group showed pictures of members with their plastic waste, together with an extrapolated amount of waste that they would generate in a year. They asked others to do the same. The types of plastic lab products were diverse, including pipette tips, used gloves, weighing boats, tubes, flasks, reagent bottles, cuvettes, and more. “I was definitely shocked by how much I used, and I think many people were, too,” Seah tells C&EN.

But can all that plastic waste be prevented?

In recent years, amid stories about plastic waste ending up on beaches and even in our diets, public opinion has started to turn against plastics. What was once considered a wonder material that was cheap, light, and clean is now being seen by many as a serious environmental problem. That shift in opinion has led some universities to rethink plastic-use policies, with much of the drive for change coming from younger members of the research community. In the UK, the University of Leeds is one of several universities that have made an ambitious pledge to completely cut out single-use plastic.

But while alternatives to plastic cups and cutlery can be found, replacing single-use items in the lab is not always so simple. For example, replacing plastic petri dishes for cell culture with glass ones might seem like a sensible switch, but the costs of using glass dishes are around 30 times as much as those of plastic ones, making it cost prohibitive for labs that use a lot of them.

Despite the challenges, some departments at Leeds have already made changes. The School of Earth and Environment is switching to reusable centrifuge racks for holding centrifuge tubes before and after separation rather than buying sets of centrifuge tubes that are preracked in polystyrene.

“To improve sustainability in science, we must work collaboratively with researchers” says Martin Farley, sustainable labs adviser at University College London (UCL). UCL is also the developer of the Laboratory Efficiency Assessment Framework, or LEAF, which is a new, independent standard for good environmental practice in labs. The standard recommends ways that lab users can reduce waste, energy, plastic, and water in the lab. The scheme was piloted at several universities in the UK during the 2018–19 school year and has just started its second year of operation. Participants are awarded bronze, silver, or gold status depending on their performance in meeting the standard.

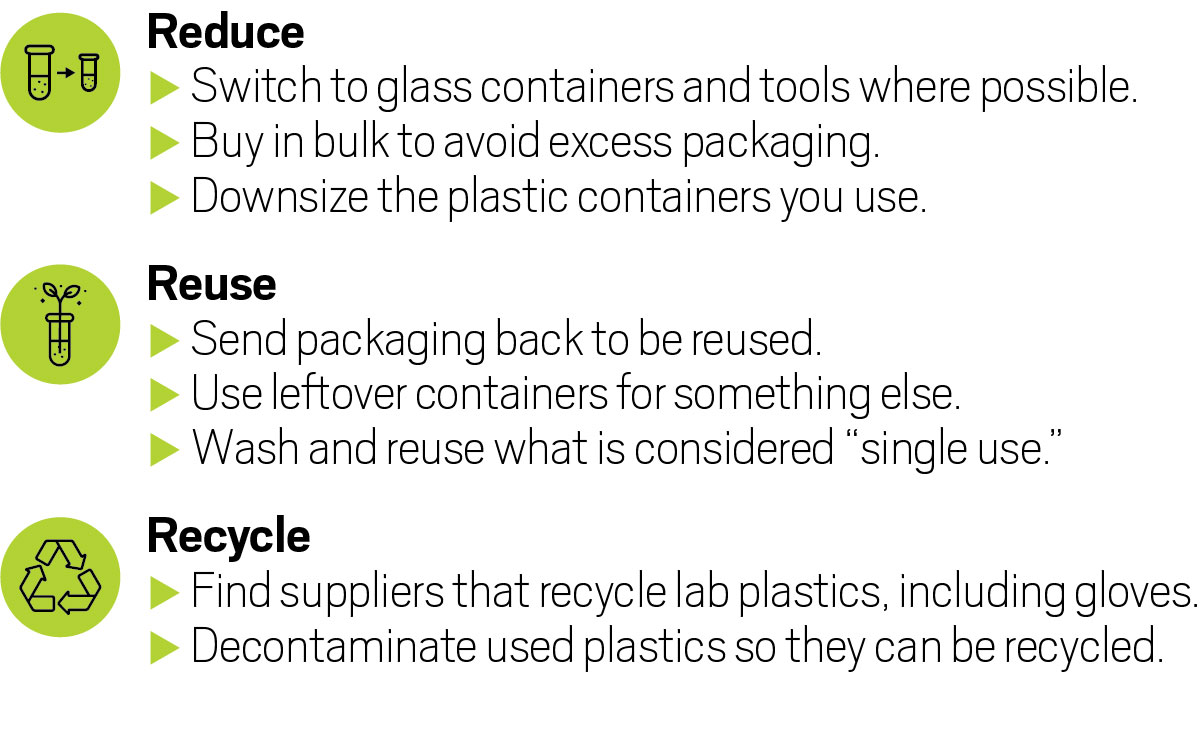

UCL is another university that has pledged to get rid of single-use plastic; its deadline is 2024. But Farley says that while the challenge might seem big right now, the trick is to celebrate every victory in reducing plastic use along the way, remembering the three Rs: reduce, reuse, and recycle.

Reduce

The biggest impact that labs can make on plastic waste, Farley says, is reducing the amount of plastic that labs use in the first place. For example, scientists could use smaller flasks or tubes if appropriate or buy products that use less material. At two institutes of the Vienna BioCenter, researchers now use refillable boxes for their pipette filter tips instead of buying new boxes every time they need more tips. They also use glass pipettes when possible.

At a glance

How to decrease your plastic footprint in the lab

Credit: C&EN/Shutterstock

The institutes made this change after requests from students and postdocs, says Martin Radolf, head of environmental health and safety at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology (IMP) and Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA), which share core facilities. His colleague Amina Zankel invited lab suppliers to discuss how they could help the institutes reduce their reliance on single-use plastic. Under the new system, researchers can refill their boxes of pipette filter tips from supplies held in the stockroom (often referred to as stores in Europe). While larger plastic pipettes are still available, Radolf says, he came up with a cunning idea to encourage people to use glass alternatives that can be washed at the sterile processing facility that is part of the scientific core facilities shared by the IMP and IMBA. “For plastic pipettes they have to go down to the cellar, to the stores,” he explains. “The glass pipettes will be placed somewhere nearer the lab,” making them more accessible than the plastic ones. Moreover, glass pipettes are free to the scientists and won’t affect lab budgets.

Scientists looking to reduce their overall plastic consumption can also pick vendors that have zero-waste manufacturing facilities or that minimize packaging when shipping and designing products. Another approach to reducing plastics is to pool resources. For example, scientists can reduce the number of reagent bottles used by buying chemicals in bulk and sharing them with other labs. At the University of Michigan, the ChEM Reuse Program allows research and teaching labs to obtain products they need for free if they’re left over from another lab. The sharing system includes chemicals and equipment, as well as materials like pipetting accessories and conical centrifuge tubes.

Reuse

When it comes to reusing plastic in the lab, there is one significant hurdle: contamination. For many labs, especially biological ones, avoiding contamination and keeping work sterile is incredibly important. But for other labs, where contamination is less of an issue, researchers could consider reusing items like weighing boats and gloves if possible, says Rachael Relph of My Green Lab, a San Diego–based nonprofit organization that works with labs to make their work more sustainable. For example, she says, accuracy or contamination might be less of an issue in teaching labs. But Relph also points out that sometimes reusable items can have comparable performance to single-use items, even in sterile procedures.

That’s been the finding of Grenova, a lab equipment firm founded by Ali Safavi in 2014. Safavi has a background in equipment that handles and moves liquids. These machines combine high-throughput and automated systems but often use a lot of plastic consumables, which can add to their financial and environmental costs.

His firm has created washing systems that can take pipette tips that are intended to be single use and then wash and sterilize them for reuse multiple times. The machine is a little like a customizable dishwasher for pipette tips. Users load it with their tips and then specify what cleaning reagent to use or if there should be soaking, ultraviolet light irradiation, or sonication steps. Different users have optimized washing protocols to get pipette tips clean enough for different lab techniques, including mass spectrometry or toxicology and immunology assays. Earlier this year, for example, researchers at the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences found their washed pipettes gave the same results as new tips for preparing small-interfering-RNA screening libraries. Since 2015, Safavi says, his company has helped labs in academia and industry reuse 93 million pipette tips, and his customers have reported that some tips can be reused 25–40 times.

Safavi hopes that cleaning tips will in time reduce the number of tips that end up in biohazard waste. Currently, many pipette tips land in biological waste management streams, where they are bagged, collected in special bins, autoclaved, and then sent to special commercial vendors for disposal. Safavi instead envisions tips used in biomedical research getting decontaminated enough through his washing machines that they can go into recycling streams when discarded.

Recycle

Recycling plastics is often a physical process. Recycling centers wash the plastics, grind them up, and then melt them to form new products. These centers need each recycling stream to contain a single type of plastic, and cross contamination can be a problem. But chemical or biological contamination introduces another wrinkle in recycling lab plastics. Even disposing of plastic waste from labs requires dealing with this contamination. The waste sometimes has to be washed with chemicals or autoclaved before sending it to a landfill or a specialist handling company that will incinerate it.

And even if the plastics are not contaminated, many local facilities or recycling contractors are hesitant to take materials from labs for general recycling because of concern about contamination. Worries about contamination even prevent scientists from recycling plastics in the lab. The University of Edinburgh recently surveyed scientists and found that while 75% reported recycling some types of plastic, many said that they were “ ‘not allowed’ to recycle anything from a lab in general recycling streams,” according to a university blog post.

In Vienna, Radolf plans to start asking his researchers to separate out the plastic packaging from cell culture labs. For safety’s sake, he adds, they will treat the waste as potentially contaminated and autoclave it, but then they will send it for general recycling. Currently, though, most recycling of lab plastic waste comes from take-back schemes with individual suppliers. Five years ago, the School of Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh became the first European university to take part in the Kimberly-Clark program that recycles single-use nitrile gloves.

Tim Calder, who manages the program at the university, says that all researchers need to do is peel off their gloves into one of four bins for separate waste streams. Noncontaminated gloves can go to either a landfill or a recycling facility, nonhazardous contaminated gloves go to an incinerator, and hazardous contaminated gloves go to a hazardous waste processing facility. When the bins get full, the facilities team collects the gloves for recycling. Once there is enough to fill a pallet, a contractor picks up the gloves and grinds them to make new materials for products such as patio furniture and planters.

Other universities are participating in take-back schemes, including those for Styrofoam boxes, pipette tip boxes, and the cartridges used in water purification systems. All these materials can be taken back by companies and either reused or recycled into different plastic products.

For years there has been a disconnect between the way scientists deal with plastic waste in their private lives and the way they do so in the lab, Relph says. But more and more, waste management companies and manufacturers are realizing the value of recycling materials from the lab. But, she adds, as great as it is to recycle, it is better to eliminate single-use plastics through reduction or reuse.

Update

On Aug. 25, 2020, this story was updated to clarify that information on a lab recycling survey came from a University of Edinburgh blog post.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter