Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Development

One molecule’s journey from discovery to market

With the help of outsourcing partners, the small biotech firm Nabriva brought lefamulin to patients by itself. Now it needs to make a profit in the tough-to-crack antibiotic business

by Michael McCoy

June 22, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 24

In November 2006, Rosemarie Riedl synthesized an antibacterial molecule that she logged into Nabriva Therapeutics’ database as BC-3781. It was not just another entry in a compound collection. In 2019, after almost 13 years of development and testing, the US Food and Drug Administration approved that same molecule, lefamulin, for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.

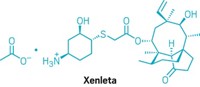

Marketed as Xenleta, lefamulin was the first antibiotic with a novel mechanism of action to win FDA approval for pneumonia in nearly two decades. With the help of contract manufacturing firms from across Europe and China, Nabriva took the drug to market without a big pharma partner.

Inventing a drug in its own labs and getting it approved solo is something few biotech firms have done. And yet it won’t be enough for the small company. Nabriva must now turn a profit on lefamulin, a goal that has eluded many independent antibiotic developers. Judging from Nabriva’s stock price, investors have their doubts that the firm will be in the black anytime soon.

Discovery

Although Nabriva’s corporate offices are in the US, and its global headquarters are in Ireland, its research efforts are based in Vienna, where the culture is decidedly more European than American. Riedl, Nabriva’s senior director of medicinal chemistry, has been with the company and its predecessor, Sandoz, since earning her PhD in pharmaceutical chemistry. And she’s not the only long-tenured employee.

“The core team has been together for a long, long time,” says Werner Heilmayer, Nabriva’s vice president for intellectual property and chemistry, manufacturing, and controls. Like Riedl, Heilmayer has been there from the start. He joined Sandoz in 1995 after graduate school and went with Nabriva when it became an independent company in 2006.

That was the year that Novartis, Sandoz’s parent company, decided it was done researching and developing new antibiotics, a field that has long been a money pit for big pharma. With about $50 million in financing from venture capital firms and its own venture arm, Novartis set the antibiotic operation off on its own.

As an independent company, Nabriva continued Sandoz’s quest for useful derivatives of pleuromutilin, an antibiotic molecule that occurs naturally in an edible mushroom sometimes called Pleurotus mutilus.

Pleuromutilin was discovered in the 1950s, and Sandoz launched two semisynthetic derivatives, tiamulin and valnemulin, as veterinary antibiotics in 1979 and 1999, respectively. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) later succeeded in creating a topical human drug, but systemic human pleuromutilins with a wider potential market eluded drug hunters for decades.

One reason for the lack of success was that, for many years, researchers were focused on finding new beta-lactam antibiotics like amoxicillin and cephalosporin, still the most widely used antibiotic class. Drug company interest in pleuromutilins finally perked up around the turn of the century as bacterial resistance to beta lactams increased, according to a review paper that Riedl and a colleague, Susanne Paukner, published in 2017 in Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine.

According to the paper, pleuromutilins work by binding to the peptidyl transferase center on the bacterial ribosome, interfering with protein production and impeding growth. It’s a unique mode of action for an antibiotic, even among those that work by blocking bacterial growth. Both mechanistic studies and in vitro experiments show a low potential for resistance to develop.

While pleuromutilin can kill bacteria in the lab, it doesn’t have what it takes to make a good drug. Chemists needed to tweak the molecule to improve properties like how long it lingers in the bloodstream.

A year after Novartis spun off Nabriva, the FDA approved the first human pleuromutilin derivative, GSK’s retapamulin. But the skin infection treatment, created by modifying the hydroxyacetyl side chain of pleuromutilin with a bicyclic N-methylpiperidine group, only works as an ointment; GSK was unable to put it into a pill or IV bag.

Xenleta at a glance

Discovered: 2006

Approved: Aug. 19, 2019

Active ingredient: Lefamulin

Indication: Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia

Mode of action: Binds to the peptidyl transferase center on the bacterial ribosome, interfering with protein production and impeding growth

Although Nabriva wasn’t first to the market, the company was determined to come up with a systemic drug. When it became independent, the firm didn’t have a viable drug candidate of its own. What it did have was a deep knowledge of pleuromutilin chemistry and well-honed skills for making derivatives.

The Nabriva researchers drew on those insights when they, like the chemists at GSK, sought to modify the hydroxyacetyl side chain. Their goal was a modification that would give the natural product the elusive balance of antimicrobial activity, solubility, and metabolic stability needed to turn a molecule into a systemic drug.

Unlike their counterparts at GSK, Riedl and her colleagues didn’t have huge compound libraries and combinatorial chemistry machinery at their disposal. Instead, they relied on old-fashioned medicinal chemistry savvy. “We always did dedicated chemistry and synthetic derivatives, compound by compound,” Heilmayer says.

In 2006, Riedl tried yet another modification of the side chain: adding an aminohydroxycyclohexyl group. The result was BC-3781, later renamed lefamulin. Riedl’s choice of that side chain involved a bit of luck, of course, but mostly it was the culmination of years of carefully directed effort. She describes the moment modestly: “I always had a good feeling about that idea and that it could solve many of the problems we had at the time.”

Development

What Riedl actually got was a mixture of diastereomers that had to be separated on a chiral high-performance liquid chromatography column. And even after separation, BC-3781 did not instill a lot of confidence. It was a difficult-to-handle amorphous salt. And the laboratory synthesis required two classical chromatographic purifications. “You cannot have these things on scale,” Heilmayer points out.

The Vienna team needed to develop a chirally selective synthesis that avoided chromatography, and a crystalline late-stage intermediate that could be isolated and purified. The team also had to come up with an acceptable salt form. “These were some of the problems we had to solve after discovering lefamulin,” Heilmayer says.

The team solved them, and by 2014, lefamulin had successfully completed Phase I and II clinical trials showing it was safe as well as effective in a small group of bacterial pneumonia patients.

Because the Vienna facility didn’t operate under the good manufacturing practice standards required by the FDA, Heilmayer had hired the chemistry outsourcing firms Aptuit and Almac to produce the small quantities of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) needed for those trials.

But Phase III clinical trials and, ultimately, commercialization would be a whole new ball game. New people, new outsourcing partners, and new money would be needed. The company hired a drug industry veteran as CEO and established a US subsidiary in Philadelphia where its clinical development team would be based. The following year Nabriva made an initial public offering of stock on the Nasdaq exchange.

One of the new executives was Steven Gelone, who is now Nabriva’s president and chief operating officer, responsible for business development and technical operations. Gelone was a good fit. Earlier in his career as an infectious disease clinician at GSK, he and his colleagues were stymied by Sandoz’s robust intellectual property (IP) around pleuromutilin derivatives.

“We kept hitting roadblocks,” he recalls. “We just could not solve the problem, in large part because the Sandoz/Novartis team, which ultimately became Nabriva, had an IP portfolio that blocked us from doing some interesting chemistry on one of the key side chains.” When Nabriva later offered Gelone a job, he couldn’t say no.

Working with the Nabriva executives in the US, Heilmayer looked to secure firms that could manufacture the quantities needed under quality systems that would satisfy inspectors with the FDA and the European Medicines Agency. “Our desire was, as best we could as a small biopharma company, to create a gold standard supply chain for this product,” Gelone says.

The critical synthetic step in lefamulin production is combining pleuromutilin with the aminohydroxycyclohexyl side chain. Heilmayer and his team needed to find large-scale suppliers of pleuromutilin and a chiral building block for the side chain, and a company to join the two pieces into the API. It also needed firms to produce the tablet and intravenous forms of the drug.

For pleuromutilin, Nabriva executives thought they had it easy. Sandoz had pioneered the fermentation of pleuromutilin to produce the two animal antibiotics, and the firm was Nabriva’s supplier during clinical development of lefamulin. But in 2014, Eli Lilly and Company acquired the Sandoz/Novartis animal health business. Suddenly, Nabriva was told to look elsewhere for pleuromutilin supply.

Heilmayer had to scramble to find a new company that could supply pleuromutilin at the required purity and with quality systems that would satisfy regulators. He soon settled on the Chinese firm SEL Biochem Xinjiang.

SEL is the world’s largest producer of pleuromutilin, using it mainly for its own production of the animal antibiotic tiamulin, according to Grace Xu, a vice president at Zhejiang University Sunny Technology, which owns SEL. For Nabriva, SEL developed a special high-purity version using higher quality standards, Xu says.

For the side chain building block, a cyclohexene carboxylic acid, Nabriva first contracted with an Indian pharmaceutical chemical company, which made it for Nabriva’s clinical trials. But because the intermediate is a liquid acid, it had to be shipped from India via sea, rather than air, creating an unacceptably weak link in the supply chain, Heilmayer says. So, with approval and commercialization of lefamulin looking more and more likely, Nabriva sought an intermediate supplier closer to home.

It ended up choosing the Irish firm Arran Chemical, which Almac acquired in 2015. Arran had the right capabilities and equipment, and Heilmayer was impressed that it was able to quote a price for the intermediate lower than what Nabriva paid the Indian firm.

Companies in Ireland have higher labor costs than do those in India, acknowledges Tom Moody, Almac’s vice president of technology development and commercialization. To offset them, Arran drew on other strengths. “In Ireland we have to do things efficiently,” he says.

Almac, which is based over the border in Northern Ireland, acquired Arran during this period, mainly for its biocatalysis and API building block scale-up skills. Almac had worked with the Irish firm for more than a decade and wanted to bring those capabilities in-house, Moody says. The chiral building block contract with Nabriva was an intriguing sweetener, he adds, because Almac had produced the API in the early days of lefamulin development and formulated it into tablets for administering to patients during clinical trials.

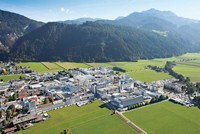

To put the intermediates together into the final lefamulin molecule, Heilmayer and his team settled on the pharmaceutical services firm Hovione at its site in Cork, Ireland, just a 3 hour drive from the site in Athlone, Ireland, where Arran makes the side chain.

In choosing Hovione, Nabriva weighed the usual factors of quality, technical fit, timing, and price. But underlying the individual considerations was the knowledge that, unlike a big drug company, Nabriva couldn’t afford to hire a second supplier in case things went wrong. “Whoever we chose,” Gelone says, “we had to be highly confident in, because we knew we weren’t going to have a second supplier when we launched lefamulin.”

Hovione, a Portuguese firm, had acquired the Cork facility from Pfizer in 2009. At the time, the plant made only one API—atorvastatin, the active ingredient in Pfizer’s cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor. But by 2014, when Hovione and Nabriva started discussions, Hovione had succeeded in bringing new products to Cork, including several APIs, recalls Paul Downing, general manager of the site. Staffing at the facility had doubled since the acquisition to about 100.

By the time Nabriva and Hovione signed a contract in 2016, it was clear that lefamulin, now in Phase III studies, would need to be made on an accelerated schedule. Hovione typically developed synthetic methods for pharmaceutical chemicals at its pilot plant in Portugal and then produced initial quantities there before transferring the process to the commercial-scale reactors in Cork. “The timeline Nabriva required meant we had to skip the middle piece,” Downing says.

Both parties knew that Hovione’s job was more than just connecting two molecules. The cyclohexene carboxylic acid from Arran had to be taken through further chemical steps to form the aminohydroxycyclohexyl side chain that Riedl had conceived in 2006. And the hydroxyacetyl group on pleuromutilin has to be activated through an exchange of sulfur for oxygen to form a sulfanylacetyl linker that couples with the side chain.

Advertisement

“It seems simple, but it’s actually a very long process that requires care and attention,” says Rui Loureiro, Hovione’s director of process chemistry development and the lead chemist on the development project. From start to finish, a production campaign takes about two months.

One area that called for special attention was phase separation. In lab tests of the reaction in Portugal, process chemists were surprised to find that three phases resulted, rather than the usual two. “We had to understand how you make sure in the plant that you take out the right phase of three phases,” Loureiro says.

Another challenge was crystallizing and recrystallizing a molecule with multiple chiral centers. “That’s how to ensure that you get the right isomers out of your reaction,” Loureiro says.

The API that Hovione manufactures in Cork is the heart of Xenleta, but for people to take it, the white powder has to be turned into tablet and IV forms. For the tablet, Heilmayer turned to Almac again.

Nabriva had first hired Almac in the early 2010s to produce the lefamulin API for Phase I and II clinical trials. At the time, says Tommy Burns, an Almac project services manager, Nabriva took the logical next step in a good relationship and asked Almac’s finished drug division to formulate the API into tablets.

Some years later, with clinical successes under its belt, Nabriva came back to Almac looking for tablet manufacturing and packaging for Phase III trials and commercial launch. “Nabriva needed a firm that could help overcome some of the development challenges they faced with the tablet,” Burns says.

To be effective, lefamulin needs to be administered in high doses, and 600 mg is tough to squeeze into even a large tablet. Moreover, because the API is sticky, Almac was not able to create a traditional pill with the necessary on-dose product identifier embossed on the surface. Instead, Burns says, Nabriva and Almac worked together to develop a nonstandard pill for which the name is applied with an inkjet printer.

For vials of the drug for intravenous delivery, Nabriva contracted with Patheon’s sterile liquid production facility in Monza, Italy. It also tapped Fresenius Kabi’s sterile liquid contract manufacturing facility in Halden, Norway, to produce special companion IV bags to which the sterile drug is added.

As Gelone explains, Nabriva scientists realized early in the development of lefamulin that its pH in solution is important and should be maintained. They worked with Fresenius on a bespoke IV bag which they created by adding a citrate buffer to the conventional saline bags made in Halden. When a health-care professional pours a vial of Xenleta into the bag, the resulting solution is close to physiologic pH, Gelone says.

In the end, producing and distributing Xenleta requires a supply chain that stretches from China to multiple sites in Europe and, ultimately, the US. Nabriva took the risk of assembling it without knowing if regulators would actually clear the drug, but the bet paid off. The FDA approved Xenleta on Aug. 19, 2019.

“We had the product in the channel and ready for patients 16 days after approval,” Gelone says.

Marketing

Nabriva’s manufacturing partners continue to refine their processes. At Hovione, for example, Loureiro is eager to develop continuous solvent extraction to decrease the amount of solvent required to recover the API. By his calculation, lefamulin generates 3% less waste than the typical API, but he says Hovione can cut waste further. “We believe there is space to improve the process.”

And Burns says Almac is in the process of moving the granulation process for Xenleta tablets from pilot to commercial scale. Once the switch is complete, Almac’s capacity to manufacture the pills will be markedly higher.

But even as Nabriva’s partners streamline production, healthy demand for Xenleta is far from a sure thing.

In the past few years several biotech firms have won FDA approval of new antibiotics that are effective against resistant bacteria, only to find physicians and hospitals reluctant to prescribe them. In 2019 alone, three small antibiotic firms—Melinta Therapeutics, Aradigm, and Achaogen—all declared bankruptcy.

Public health experts say doctors and hospitals need new medicines to fight antibiotic-resistant infections, yet the companies that invent them too often find few customers.

“One of the conundrums that’s very unique for anti-infectives is the strong desire to have innovation available but not wanting to use that innovation for fear you’re going to ruin it by creating resistance,” Gelone says. The health-care community thus thoroughly reviews the differentiating characteristics of a new antibiotic to understand the patients for which it is best suited. “I’ve run the committees that do it, and the process takes time,” he says.

Nabriva contends that Xenleta falls in the right place. Pleuromutilin antibiotics, the firm says, have a lower propensity for resistance than most established antibiotics because they bind to bacterial ribosomes in a unique way and via multiple interactions. And lefamulin has the advantage of being approved in both IV and oral forms, meaning it has the potential to be administered first in a hospital and later at home.

New antibiotics aren’t going to be billion-dollar-a-year drugs, Gelone acknowledges. “There has to be a perceived unmet medical need that the physician community believes this product will address,” he says. “That’s where lefamulin fits in.”

Nabriva is finding the process of fitting in to be slow. In April, the company announced that it is laying off its hospital-oriented salesforce of 66 people, more than a third of its overall staff. Nabriva described the decision as part of a new strategy of focusing on community health-care professionals. Restrictions on interacting with hospital personnel during the coronavirus pandemic also played a role in the layoffs.

On May 11, Nabriva reported that it had product sales in the first quarter of 2020 of only $156,000. The firm also disclosed that it was in danger of being delisted from the Nasdaq stock market because its shares were trading for less than $1.00. In early 2017 they were changing hands for more than $12.50.

Still, Gelone is optimistic. European regulators just handed down a positive opinion, and Nabriva is working with its partner in China, Sinovant, on approval there. He notes that Xenleta could play a role in treating people infected with the novel coronavirus who also have contracted pneumonia.

In Vienna, Heilmayer and Riedl remain proud of what Nabriva has accomplished. Heilmayer wonders if a larger company would have stuck with the compound through the tougher moments. “They establish certain thresholds, and if you don’t achieve these thresholds, the compound is gone,” Heilmayer says of big drug firms. “In the biotech world, if you have a challenge you will always look for ways to overcome it.”

Today, Heilmayer and Riedl are tackling new challenges. Heilmayer continues to work with Nabriva’s outsourcing partners to support and troubleshoot Xenleta manufacturing. In one recent program, they elucidated and synthesized a new impurity encountered during large-scale API manufacturing.

As for Riedl, she and her colleagues are working on next-generation pleuromutilin antibiotics as well as other projects that she is keeping close to the vest. “Stay tuned for the next molecules from Nabriva,” she says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter