Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Concerns about scientist immigration to the US have amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic

Trump adds new visa restrictions as anti-immigration rhetoric has risen

by Andrea Widener

June 29, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 25

Support nonprofit science journalism

C&EN has made this story and all of its coverage of the coronavirus epidemic freely available during the outbreak to keep the public informed. To support us:

Donate Join Subscribe

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused research disruptions and career delays for many chemistry graduate students and postdoctoral scholars worldwide. But in the US, scientists were already worried about the effect that President Donald J. Trump’s administration is having on the flow of people coming into the country to study or work. Some are concerned that the pandemic is making that situation worse.

COVER STORY

In the US, concerns about immigration have amplified

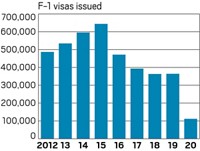

International student applications to the US have declined since Trump took office, according to the Council of Graduate Schools. The drop in applications is something that most experts attribute to anti-immigrant rhetoric from the administration.

The White House has moved beyond rhetoric during the pandemic. On June 22, Trump issued a temporary ban on H-1B and other non-immigrant visas often used by companies and universities to hire international scientists, including postdocs. He also extended a previous order that halted processing of some green card applications for permanent residency.

By the numbers: International scientists in the US

1.6 million

Number of international scientists studying or working in the US as part of the Student and Exchange Visitor Program in 2018, down 1.7% from 2017

70,000

Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics students working in the US through an Optional Practical Training visa extension in 2018, up 8% from 2017

36%

Proportion of chemistry doctoral degrees awarded to students on a non-immigrant visa, out of a total of 2,810 degrees awarded in 2018

189

Scientists alleged by the US National Institutes of Health to have violated foreign-influence reporting rules since 2018; of these, 82% were Asian and 14% were white

54

Scientists who resigned or were dismissed from their jobs since 2018 because of alleged violation of US National Institutes of Health foreign-influence reporting rules

Sources: US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, National Science Foundation, and National Institutes of Health

In addition, Trump has issued a vaguely-worded executive order limiting visitors associated with China’s “military-civil fusion strategy.” He also shut down some flights from China to the US. In Congress, a bill sponsored by several Republicans would stop immigration from China altogether. Those moves could have a significant impact on scientists’ ability to get visas at the same time that closed borders and consulates along with canceled flights are keeping them from traveling.

Schools outside the US are taking advantage of the resulting uncertainty, says University of Chicago chemistry professor Weixin Tang. One example she has seen: a Hong Kong university is advertising for PhD students and postdocs, even though it isn’t their usual hiring season. “They’re opening up slots to recruit students and postdocs who were scheduled to come to the US,” she says. In addition,

In addition, attacks on Chinese scholars are of particular concern to scientists given the large numbers of students and postdocs in science fields, including chemistry, who historically have come to the US for training. Contributing to the unease are the US Department of Justice’s efforts to prosecute scientists who collaborate with China, an initiative started as part of a larger US-China trade war.

Peter Kilpatrick, provost at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), says his school has seen declining enrollment from China. The Chinese government does overreach in its technology-gathering efforts, he says, but “the vast majority of the people in China are not associated with the government, and they’re not responsible for espionage and [intellectual property] theft, etc. So the question is where do you draw the line? How do you parse who to throw the doors open to and who to say ‘We need to be careful.’ ”

Many universities are particularly concerned about rumored threats to optional practical training (OPT), which allows students and postdocs to extend their student visa to do internships or work in the US. For science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) students, visas may be extended up to 3 years under OPT. Trump has so far not restricted OPT extensions, although he could still do so in the future.

At IIT, loss of OPT would be a threat to the institution itself, Kilpatrick says. The school relies on tuition from its large number of master’s degree programs.

“If OPT goes away, we lose all of our international students. I mean, what would be their motivation for coming?” he asks. Many people come to the US because they can combine getting a degree with the chance to get work experience and gain connections in the US. Without that, it could be “the death knell for higher education in this country,” Kilpatrick says.

Chuan He, a University of Chicago chemistry professor, says loss of OPT “would be a pure disaster.” OPT provides a critical opportunity at a key time in international scientists’ careers for them to transition from one job to another, and it is vital to keep highly trained students with critical skills in the country, He says. “We want them to stay, right?”

Computational and theoretical chemist Varun Rishi used OPT to work as a postdoc after he got his PhD at the University of Florida: first at Virginia Tech and then, since October 2019, at the California Institute of Technology.

COVER STORY

In the US, concerns about immigration have amplified

In February, Rishi went to visit his family in India, and now he’s stuck there, working remotely on a desk set up in a bedroom. He hopes he gets to return to Caltech soon. If not, “that means that I spent more than half of my time out of the country and outside of the lab. That’s going to affect everything,” he says.

Rishi says Caltech was transitioning him from OPT to an H-1B visa, but that is now even more up in the air after Trump’s most recent immigration ban. Even before the announcement, Rishi was worried about new US immigration restrictions, he says. “Many of the things that you don’t think would happen are happening.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter