Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

C&EN’s molecules of the year for 2018

Chemistry news outlet highlights compounds that made headlines this year

by Celia Henry Arnaud

December 4, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 49

Russian nerve agents found in UK

Part of the Novichok family of nerve agents, these compounds burst onto the world stage in March when one of them—most likely A-234—was used in the attempted murder of Sergei Skripal, a former Russian double agent living in Salisbury, England, and his daughter Yulia.

Simple but elusive synthesis cracked

Scientists first reported a synthesis of dimethylcalcium 60 years ago, but that feat was never replicated. This year, German chemists finally reported another synthesis of the seemingly simple molecule, which could lead to new catalysts or reagents. The trick was finding appropriate starting materials and devising a way to purify a notoriously contaminated reactant (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b12984). The researchers used the dimethylcalcium to make a heavy Grignard reagent and a terminal calcium methyl compound.

Japanese team paid homage to the ringed planet

Chemists at the Tokyo Institute of Technology made a nano-Saturn as a supramolecular complex consisting of C60 trapped within a large hydrocarbon ring of substituted anthracene units (Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201804430). Weak CH-π interactions hold the system together.

First new class of stereoisomers identified in half a century

While making porphyrin macrocycles containing a boron-oxygen-boron bridge, an international team of researchers discovered a new type of isomer. So-called akamptisomers result from a bond-angle inversion in which the central atom in a bent, singly bonded trio of different atoms flexes in the opposite direction (Nat. Chem. 2018, DOI: 10.1038/s41557-018-0043-6). In the case of the researchers’ macrocycles, the oxygen atom in the bridge does the flexing, moving back and forth to either side of the porphyrin ring.

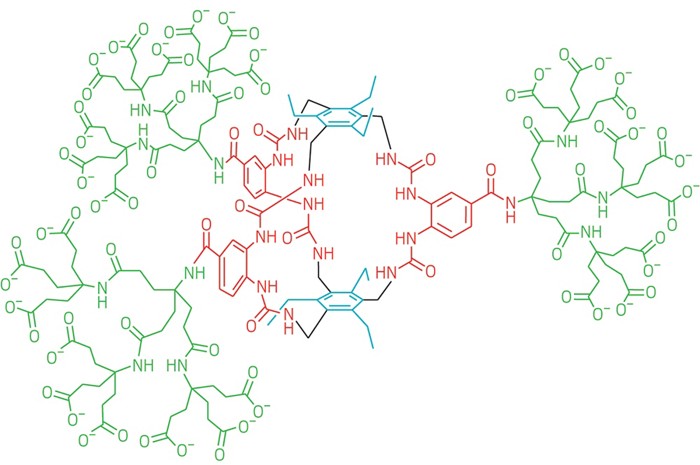

Death cap mushroom toxin synthesized

Researchers at the University of British Columbia devised a route for making α-amanitin, a toxin produced by the death cap mushroom that is of interest as a possible anticancer agent. To make the bicyclic octapeptide, chemists installed a delicate 6-hydroxy-tryptathionine cross-link (blue), performed an enantioselective synthesis of the toxin’s (2S,3R,4R)-4,5-dihydroxyisoleucine group (red), and added a sulfoxide (green) with the correct stereochemistry, which they achieved with a bulky oxidant and judicious solvent selection (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b12698).

Radical polymer broke conductivity record

Radical polymers are typically less conductive than their conjugated relatives, which have delocalized bonds that can shuttle electrons. A new nonconjugated organic radical polymer, however, has electrical conductivity 1,000 times as great as that of other organic radical polymers and therefore might be integrated into batteries or displays. The material poly(4-glycidyloxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl), or PTEO, features a flexible ether backbone and pendant nitroxide radicals (Science 2018, DOI: 10.1126/science.aao7287). Researchers at Purdue University achieved the elevated conductivity by heating the polymer to 80 °C and cooling it to room temperature. During that process, the polymer backbone bent and allowed the nitroxide groups to form conductive pathways throughout the material.

Chemical synthesis yielded holey graphene

Scientists in Spain used chemical synthesis to make graphene with precisely positioned nanoscale holes, giving it semiconducting properties, and incorporated the material into a working transistor (Science 2018, DOI: 10.1126/science.aar2009). The researchers created the perforated graphene by subliming diphenyl-10,10′-dibromo-9,9′-bianthracene (DP-DBBA) onto a gold substrate under ultrahigh vacuum, where it polymerized at about 200 °C. Further heating steps at higher temperatures cyclized and dehydrogenated the polymer to form nanoribbons and then caused the ribbons to fuse with holes in between.

Chemists tied a big knot

The 324-atom continuous loop weaves over and under itself at nine crossing points and is the most complex molecular knot published to date (Nat. Chem. 2018, DOI: 10.1038/s41557-018-0124-6). Chemists at the University of Manchester made the structure by stitching together six long building blocks containing alkene groups at each end and three bipyridyl groups in the middle. These ligands twisted around six iron ions, binding to them through their bipyridyl nitrogen atoms. Using a common ruthenium catalyst, the team connected all the ligands to one another with a ring-closing metathesis reaction and then removed the iron to yield the final, knotted loop. Although these types of knots are viewed as demonstrations of synthetic prowess, the researchers hope they might one day be used as catalysts or for other applications.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter