Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Electronic Materials

Bichlien Nguyen

This IT innovator develops electronics that are more environmentally friendly

by Celia Henry Arnaud, special to C&EN

July 15, 2022

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 100, Issue 25

Credit: Will Ludwig/C&EN/Tim Peacock/Courtesy of Bichlien Nguyen

Many computer circuit boards might be green in color, but electronics aren’t particularly environmentally friendly. They are made from materials that are becoming harder to mine, and they draw large amounts of energy.

Bichlien Nguyen wants to change that. As a chemist and principal researcher at Microsoft Research, she’s designing and making more environmentally friendly materials that will transform electronics and the infrastructure around them, including the humble computer mouse and even large data centers.

Advertisement

Nguyen’s interest in chemistry started with her father, who was a laboratory technician at Dupont. She remembers visiting the company with him for Take Your Daughter to Work Day. When someone asked her what she wanted to do when she grew up, Nguyen said she wanted to be the CEO of Dupont. She didn’t follow that exact path, but she credits the experience as a formative one for setting her on the road to science.

Nguyen started at Microsoft as a postdoc working on ways to store digital data in DNA molecules. At Microsoft and elsewhere, researchers want to translate the electronic ones and zeros that a computer normally reads and writes into the base pairs of DNA. Such a system could provide stable, high-density archival data storage. Nguyen didn’t have experience with DNA or data storage. But the company was looking for someone who had experience in surface chemistry.

Microsoft researchers wanted to understand what was needed to make a DNA data storage system practical, Nguyen says. Writing and reading data encoded in DNA are bottlenecks in the process.

“Her work within Microsoft on the DNA data storage initiative has really been fundamental in kick-starting this field,” says Jake Smith, a colleague of Nguyen’s at Microsoft and a fellow alum of Kevin Moeller’s lab at Washington University in St. Louis, where Nguyen did her PhD. She devised an electrochemical way to make the spots where the DNA gets synthesized smaller and closer together. This change increased the storage capacity of DNA and increased the rate of writing DNA data to megabytes per second. Microsoft researchers think the rate needs to hit gigabytes per second for this technology to be commercially viable and cost competitive, so the team still has a ways to go.

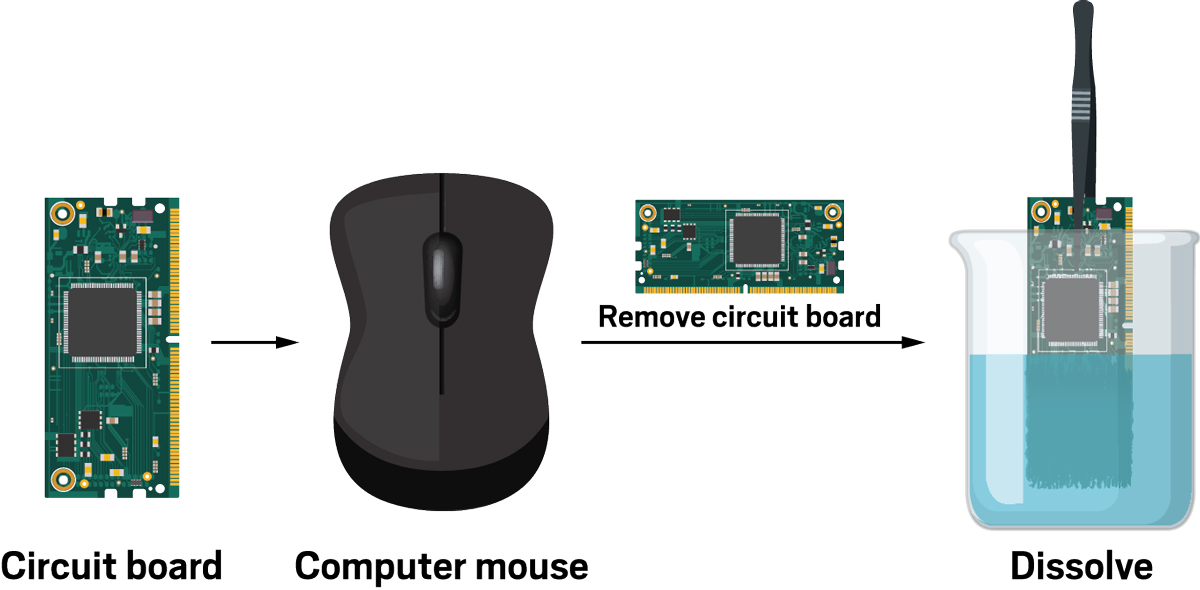

Nguyen is now working to improve the recyclability of electronic components. “I told my manager that we should work on something where we’re able to enable a circular life cycle for electronics,” Nguyen says. To that end, she’s collaborating with others to build a computer mouse with a biodegradable circuit board. Much of this effort culminated in Project Zerix, which unites collaborators from multiple disciplines to develop materials with net-zero environmental impact for the IT industry.

Nguyen’s “strength is that while she takes on nontraditional problems, Bichlien thinks like a traditional chemist,” Moeller says. “She thinks mechanism, she thinks about the methodology that’s involved, and she thinks about the fundamental chemistry that lies underneath it. That’s what allows her to solve these kinds of issues.”

Nguyen says the next industrial revolution will need scientists who can break down the silos between chemistry, biology, materials science, computer science, and computer engineering. “I see the value of my research as the fact that I can synthesize and mix all of these together and come up with something that is really important for the future.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: Microsoft Research

Age: 34

PhD alma mater: Washington University in St. Louis

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

If I were an element, I'd be: “Why choose one element when I can choose all of them? Elements make chemistry spicy, colorful, and fun.”

My alternate-universe career: “I have too many alternative career paths, including human-computer interaction researcher, astronaut, paleontologist, archaeologist, and historian.”

See the Talented 12 present their work at a virtual symposium Sept. 19, 20, and 21. Register for free at cenm.ag/t12symposium.

|

|

Many computer circuit boards might be green in color, but electronics aren’t particularly environmentally friendly. They are made from materials that are becoming harder to mine, and they draw large amounts of energy.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: Microsoft Research

▸ Age: 34

▸ PhD alma mater: Washington University in St. Louis

▸ Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: “Why choose one element when I can choose all of them? Elements make chemistry spicy, colorful, and fun.”

▸ My alternate-universe career: “I have too many alternative career paths, including human-computer interaction researcher, astronaut, paleontologist, archaeologist, and historian.”

Bichlien Nguyen wants to change that. As a chemist and principal researcher at Microsoft Research, she’s designing and making more environmentally friendly materials that will transform electronics and the infrastructure around them, including the humble computer mouse and even large data centers.

Nguyen’s interest in chemistry started with her father, who was a laboratory technician at Dupont. She remembers visiting the company with him for Take Your Daughter to Work Day. When someone asked her what she wanted to do when she grew up, Nguyen said she wanted to be the CEO of Dupont. She didn’t follow that exact path, but she credits the experience as a formative one for setting her on the road to science.

Nguyen started at Microsoft as a postdoc working on ways to store digital data in DNA molecules. At Microsoft and elsewhere, researchers want to translate the electronic ones and zeros that a computer normally reads and writes into the base pairs of DNA. Such a system could provide stable, high-density archival data storage. Nguyen didn’t have experience with DNA or data storage. But the company was looking for someone who had experience in surface chemistry.

Microsoft researchers wanted to understand what was needed to make a DNA data storage system practical, Nguyen says. Writing and reading data encoded in DNA are bottlenecks in the process.

“Her work within Microsoft on the DNA data storage initiative has really been fundamental in kick-starting this field,” says Jake Smith, a colleague of Nguyen’s at Microsoft and a fellow alum of Kevin Moeller’s lab at Washington University in St. Louis, where Nguyen did her PhD. She devised an electrochemical way to make the spots where the DNA gets synthesized smaller and closer together. This change increased the storage capacity of DNA and increased the rate of writing DNA data to megabytes per second. Microsoft researchers think the rate needs to hit gigabytes per second for this technology to be commercially viable and cost competitive, so the team still has a ways to go.

Nguyen is now working to improve the recyclability of electronic components. “I told my manager that we should work on something where we’re able to enable a circular life cycle for electronics,” Nguyen says. To that end, she’s collaborating with others to build a computer mouse with a biodegradable circuit board. Much of this effort culminated in Project Zerix, which unites collaborators from multiple disciplines to develop materials with net-zero environmental impact for the IT industry.

Nguyen’s “strength is that while she takes on nontraditional problems, Bichlien thinks like a traditional chemist,” Moeller says. “She thinks mechanism, she thinks about the methodology that’s involved, and she thinks about the fundamental chemistry that lies underneath it. That’s what allows her to solve these kinds of issues.”

Nguyen says the next industrial revolution will need scientists who can break down the silos between chemistry, biology, materials science, computer science, and computer engineering. “I see the value of my research as the fact that I can synthesize and mix all of these together and come up with something that is really important for the future.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter