Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Climate Change

Cate Levey

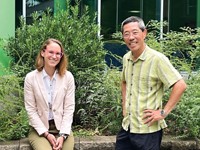

This climate-tech chemist engineers food and building materials to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

by Matt Blois

July 15, 2022

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 100, Issue 25

Credit: Will Ludwig/C&EN/Tim Peacock/Chris Dembia

In 2014, with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and about a year of professional experience working on plywood adhesives, Cate Levey sent an email to Patrick Brown, the CEO of Impossible Foods, which at the time was a buzzy start-up in the early stages of developing a plant-based meat substitute.

She told Brown that she wanted to work at Impossible Foods, where she thought she could make an impact on climate change and public health. He responded, telling her that the company would soon be hiring. She landed a job there shortly afterward.

Advertisement

“I know very well how much a motivated person who starts with very little specialized experience can accomplish and learn if they’re motivated by what they’re doing,” Brown tells C&EN in an email. “We prioritize raw potential, curiosity, imagination, initiative and desire to learn and take on hard challenges. . . . Those were all qualities that made Cate successful.”

At Impossible Foods, Levey helped re-create the texture of beef in the company’s signature burger. She spent part of her time in a materials science lab, investigating whether plant-derived proteins could behave like meat proteins. She also worked in a kitchen, where she cooked and ate plant-based meat prototypes.

Levey stayed with Impossible Foods for more than 7 years and helped launch the Impossible burger in 2016. Then she started looking for an even bigger problem to tackle. She landed on carbon capture, a technology that hasn’t been widely deployed yet even though many climate scientists say it will be necessary to stop the worst consequences of climate change.

“There were not enough people and not enough scientists and engineers working on this fundamentally difficult problem,” she says. “If we want those solutions to be available in 5 or 10 years, we need to start yesterday.”

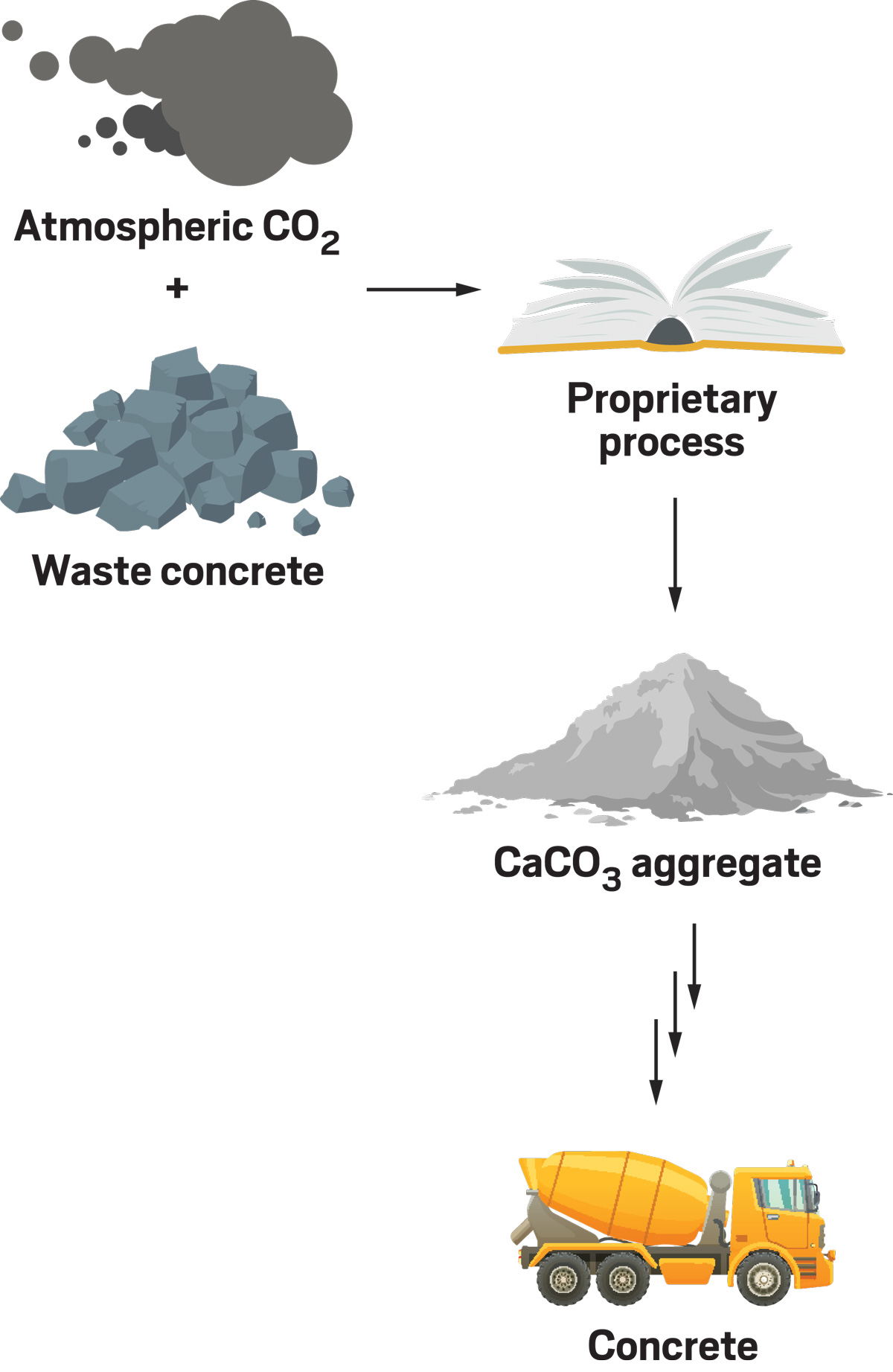

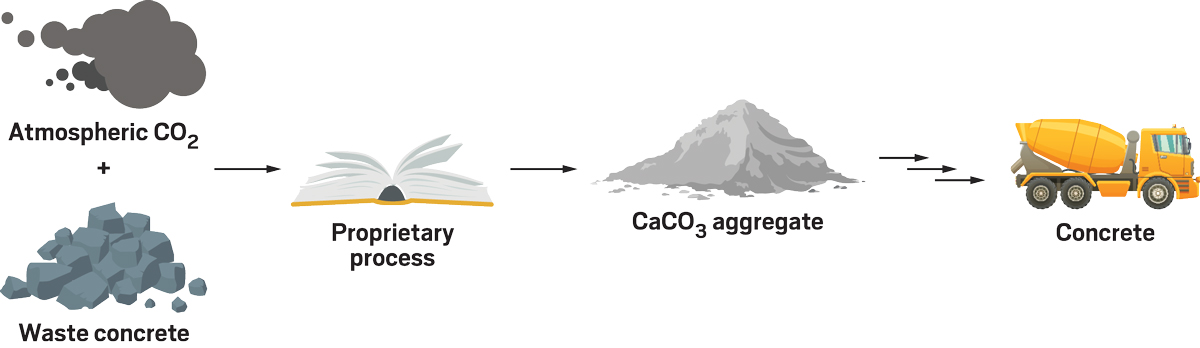

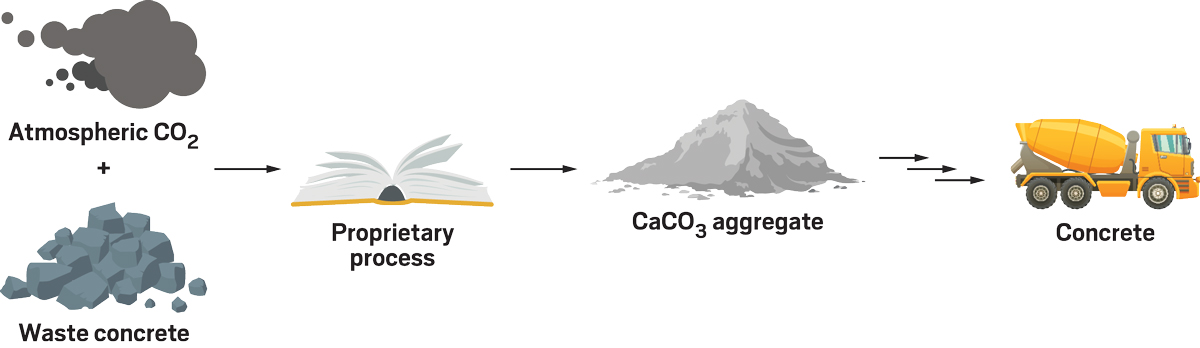

She sent her résumé to Blue Planet Systems, a company that mineralizes carbon dioxide to produce aggregate, the rocks and sand used in concrete. Levey saw working at the company as another opportunity to contribute to a moon shot. Cement, the glue that binds the rocks and sand in concrete together, accounts for 8% of global CO2 emissions. Blue Planet claims that carbon stored in its aggregate can more than offset the emissions associated with the cement, making the concrete carbon negative.

When Levey applied, “I’m not even sure we had an opening,” Blue Planet CEO Brent Constantz says. He says her background was too good to pass up. He hired her in early 2021.

At Blue Planet, Levey studies the various crystal forms of calcium carbonate, the material used to make the aggregate. She says understanding how the crystallization process works helps Blue Planet control CO2 mineralization.

Levey is relentless when it comes to understanding the principles underlying a problem she’s working on, according to Constantz. If typical approaches don’t work, she’ll seek out new analytical methods to find answers. “She keeps on peeling the onion,” he says.

Levey says that kind of creativity is one of her superpowers. She says the problems she worked on at both Blue Planet and Impossible Foods didn’t have obvious solutions, which gave her the opportunity to approach them with some oblique solutions.

“Both of these [fields] are looking at problems from a new perspective,” she says. “There’s a lot of room for approaching things from a different angle.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: Blue Planet Systems

Age: 31

Alma mater: Emory University

Hometown: Gainesville, Florida

If I were an element, I'd be: “Sodium. As an ion, I’d want to be part of the ocean, and I could also bring out the flavor in food.”

My alternate-universe career: “I’d probably run a thrift store. I enjoy the treasure-hunt aspect and the satisfaction from finding great items, I like the efficiency of the more circular economy, and I enjoy working with my hands in the physical world.”

See the Talented 12 present their work at a virtual symposium Sept. 19, 20, and 21. Register for free at cenm.ag/t12symposium.

|

|

In 2014, with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and about a year of professional experience working on plywood adhesives, Cate Levey sent an email to Patrick Brown, the CEO of Impossible Foods, which at the time was a buzzy start-up in the early stages of developing a plant-based meat substitute.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: Blue Planet Systems

▸ Age: 31

▸ Alma mater: Emory University

▸ Hometown: Gainesville, Florida

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: “Sodium. As an ion, I’d want to be part of the ocean, and I could also bring out the flavor in food.”

▸ My alternate-universe career: “I’d probably run a thrift store. I enjoy the treasure-hunt aspect and the satisfaction from finding great items, I like the efficiency of the more circular economy, and I enjoy working with my hands in the physical world.”

She told Brown that she wanted to work at Impossible Foods, where she thought she could make an impact on climate change and public health. He responded, telling her that the company would soon be hiring. She landed a job there shortly afterward.

“I know very well how much a motivated person who starts with very little specialized experience can accomplish and learn if they’re motivated by what they’re doing,” Brown tells C&EN in an email. “We prioritize raw potential, curiosity, imagination, initiative and desire to learn and take on hard challenges. . . . Those were all qualities that made Cate successful.”

At Impossible Foods, Levey helped re-create the texture of beef in the company’s signature burger. She spent part of her time in a materials science lab, investigating whether plant-derived proteins could behave like meat proteins. She also worked in a kitchen, where she cooked and ate plant-based meat prototypes.

Levey stayed with Impossible Foods for more than 7 years and helped launch the Impossible burger in 2016. Then she started looking for an even bigger problem to tackle. She landed on carbon capture, a technology that hasn’t been widely deployed yet even though many climate scientists say it will be necessary to stop the worst consequences of climate change.

“There were not enough people and not enough scientists and engineers working on this fundamentally difficult problem,” she says. “If we want those solutions to be available in 5 or 10 years, we need to start yesterday.”

She sent her résumé to Blue Planet Systems, a company that mineralizes carbon dioxide to produce aggregate, the rocks and sand used in concrete. Levey saw working at the company as another opportunity to contribute to a moon shot. Cement, the glue that binds the rocks and sand in concrete together, accounts for 8% of global CO2 emissions. Blue Planet claims that carbon stored in its aggregate can more than offset the emissions associated with the cement, making the concrete carbon negative.

When Levey applied, “I’m not even sure we had an opening,” Blue Planet CEO Brent Constantz says. He says her background was too good to pass up. He hired her in early 2021.

At Blue Planet, Levey studies the various crystal forms of calcium carbonate, the material used to make the aggregate. She says understanding how the crystallization process works helps Blue Planet control CO2 mineralization.

Levey is relentless when it comes to understanding the principles underlying a problem she’s working on, according to Constantz. If typical approaches don’t work, she’ll seek out new analytical methods to find answers. “She keeps on peeling the onion,” he says.

Levey says that kind of creativity is one of her superpowers. She says the problems she worked on at both Blue Planet and Impossible Foods didn’t have obvious solutions, which gave her the opportunity to approach them with some oblique solutions.

“Both of these [fields] are looking at problems from a new perspective,” she says. “There’s a lot of room for approaching things from a different angle.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter