Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Facing chemistry’s destructive side

Our drive to create, extract, and use molecules in novel ways is inextricably tied to disasters—some that erupted in just moments and others that unfolded over decades. Stemming the damage these disasters have caused to the environment and human health and preventing future crises will be key challenges in the next century

by Chris Gorski , Alla Katsnelson, special to C&EN

August 11, 2023

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 101, Issue 26

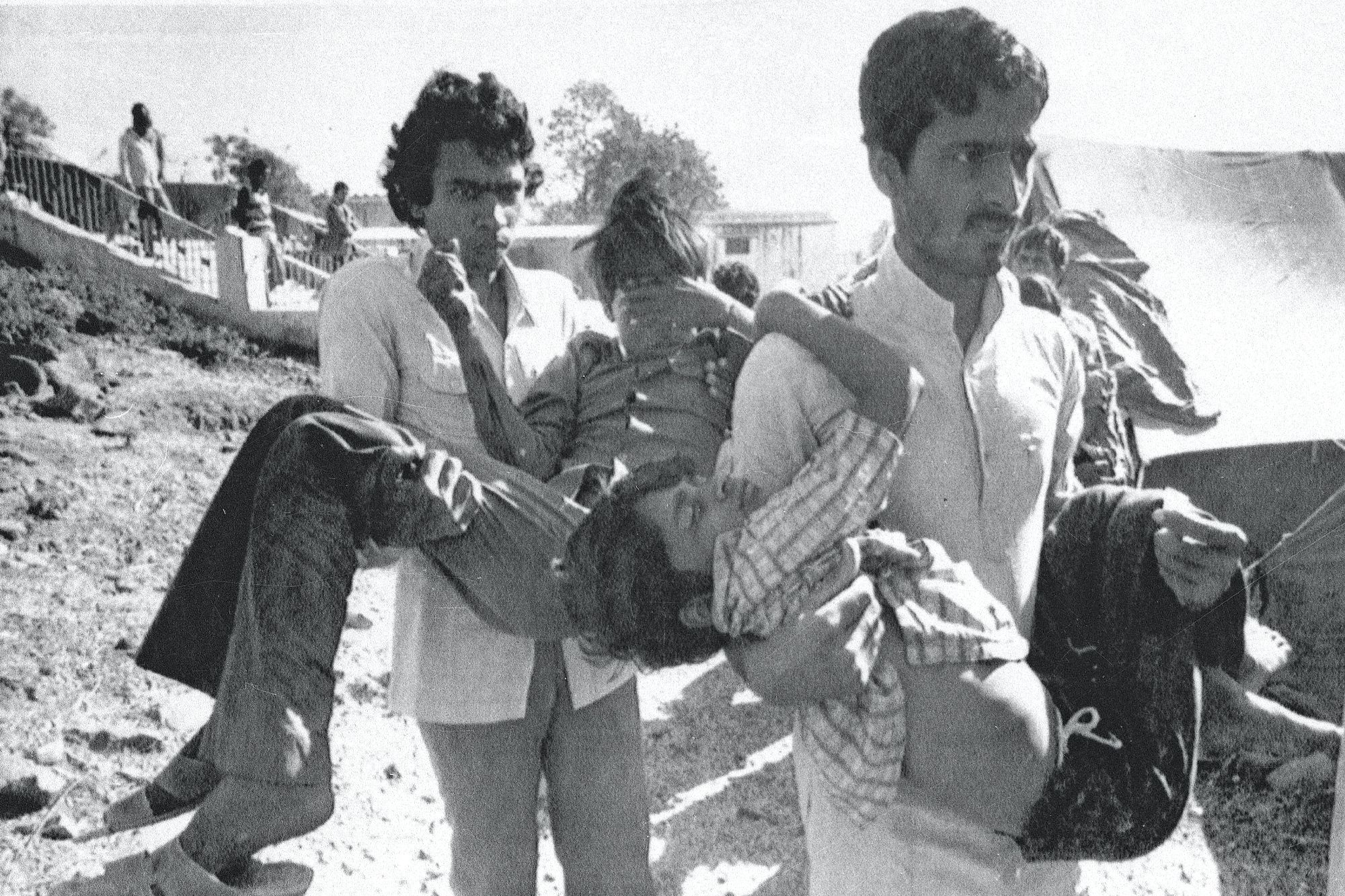

Two men in Bhopal, India, carry children blinded by poisonous gas leaked from a factory in December 1984.

Credit: AP Photo/Sondeep Shankar

Bhopal, 1984

An industrial accident at a Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, wrought death and destruction on a massive scale. A methyl isocyanate tank became dangerously hot and began leaking late on the night of Dec. 2, 1984. As pressure built up in the tank, a safety valve failed, spewing more than 40 metric tons of toxic gas into the air. At least 3,800 people died immediately. Many thousands died later, and tens or even hundreds of thousands were sickened. An estimated half-million people were exposed to the gas. People in the area continue to experience health problems, and concerns about lingering environmental effects remain. Many consider the Bhopal accident to have been the worst industrial disaster in history. “The tragedy at Bhopal still boggles the mind,” C&EN editor Michael Heylin writes in 1994 in an article commemorating the disaster’s 10th anniversary. The tragedy served as a wake-up call for the chemical industry, spurring the widespread adoption of new safety regulations.

Workers test an insecticidal fogging machine at Jones Beach in New York.

Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images

DDT

The 1939 discovery that DDT was a powerful insecticide earned Paul Hermann Müller the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Its use quickly grew worldwide because it was so effective at stopping the spread of insect-borne malaria and typhus. But the substance has a massive downside: it becomes concentrated in the food chain and endangers humans and wildlife. DDT disrupts the nervous and endocrine systems and is a likely carcinogen. Although journalists and researchers raised concerns about the chemical as early as the 1940s, Rachel Carson’s landmark 1962 book, Silent Spring, played a key role in revealing how DDT wreaked environmental damage and endangered birds and marine life. Recent research has revealed that DDT’s effects on people extend across generations, to the children and grandchildren of those exposed to the insecticide. DDT was banned in the US in 1972, and its use around the world is limited by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, though it can still be used for malaria control.

Microplastic particles are ubiquitous in the environment.

Credit: Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program

Microplastic pollution

Plastics’ convenience, low cost, and durability have made these materials ubiquitous—and disposable. Researchers estimate that most of the 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic produced to date now lies in landfills or ends up in oceans as pollution. After about 75 years of mass-producing plastics, we are awash in tiny pellets of plastic debris less than 5 mm in diameter. Scientists first observed these particles in the 1970s but did not name them microplastics until 2005. Wind and water have carried these plastic pieces to all corners of the earth—the Arctic Ocean and the Antarctic snow, the Andes Mountains, and the deserts of Iran. We consume these particles in table salt, seafood, and the air we breathe. Microplastics’ effects on human health are not yet clear, but studies show that they can build up in the guts of animals and cause internal injuries, as well as boost inflammation. Stemming microplastic pollution starts with reducing production, scientists say. “We have to move away from a throwaway mindset,” environmental physicist Laura Revell of the University of Canterbury told C&EN in February 2022.

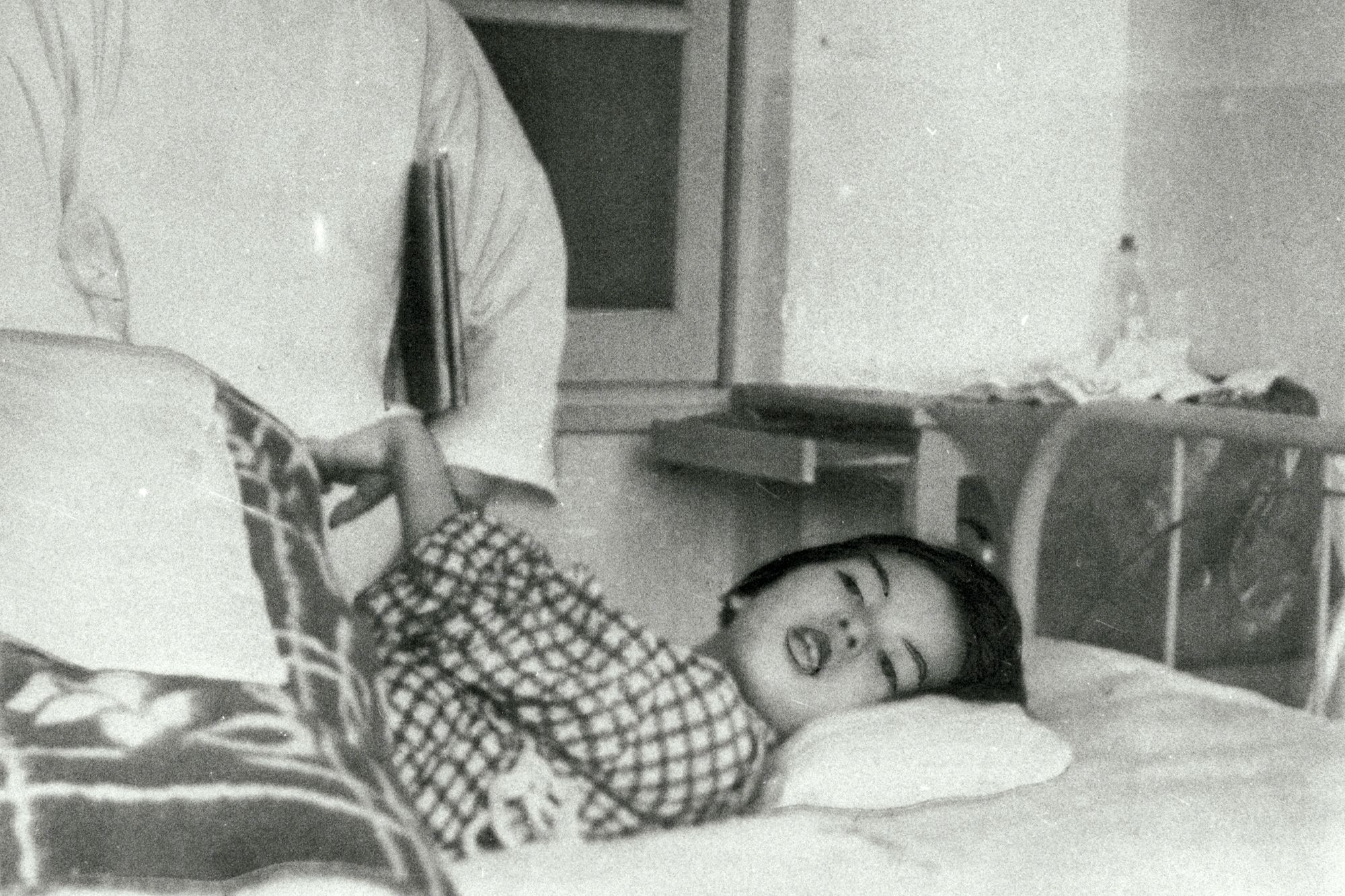

A child lies hospitalized from Minamata disease in 1960 in Minamata, Japan.

Credit: The Asahi Shimbun/Getty Images

Minamata disease, 1950s–60s

Starting in 1932, a Chisso chemical factory producing acetaldehyde in Minamata, Japan, discharged methylmercury into the Minamata Bay. In 1951, the factory changed cocatalysts from manganese dioxide to ferric sulfide and soon also increased the use of a mercuric sulfate catalyst, ratcheting up the volume of discharged methylmercury. Local doctors soon observed a spate of neurological illnesses and began suspecting the area’s seafood as a cause. The first official cases of Minamata disease, including those of two young girls, were reported in 1956. It then took 12 years of research and advocacy for the government to officially name methylmercury pollution as the culprit.

More than 2,000 people from the area were officially diagnosed with Minamata disease, which causes severe neurological symptoms. More than 1,000 of the people with the disease died, and thousands of others likely experienced symptoms. Countries around the world now recognize methylmercury’s severe effects on human health and the environment. In 2013, about 140 nations agreed to the Minamata Convention on Mercury, which was designed to curb the use of mercury in industry.

A researcher at the US Environmental Protection Agency studies per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances contamination in February 2023.

Credit: Associated Press

PFAS

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, have been widely used in industrial and commercial products since the 1940s. These substances, nicknamed forever chemicals, have an impressive ability to repel water, stains, and grease. One early example, Teflon, was serendipitously invented by DuPont in 1938 and marketed after World War II as a nonstick coating for cookware. Today, thousands of PFAS have been synthesized for use in adhesives, construction materials, cleaning products, paints and coatings, cosmetics, textiles, packaging, electronics, explosives, foam fire retardants, and more. In recent decades, however, evidence has emerged from animal and human studies revealing these molecules’ harmful effects. PFAS can cause some cancers, disrupt the endocrine system, and interfere with reproduction and fetal development, as well as have other detrimental effects. Companies have phased out several especially harmful PFAS but are replacing some with new, poorly tested alternatives. Governments are working to develop regulations restricting PFAS production, but these degradation-resistant materials have accumulated widely in the environment—and in our bodies. Although technologies are emerging that can destroy these chemicals, so far there’s no clear path forward for cleaning up PFAS pollution.

A state police officer posts warning signs in Seveso, Italy, after the area's contamination by dioxin in 1976.

Credit: Hulton Deutsch/Getty Images

Seveso, 1976

On July 10, 1976, near Seveso, Italy, a valve burst at a chemical factory owned by a subsidiary of Roche. The accident released a cloud of 2,3,7,8-tetracholorodibenzo-p-dioxin, known as TCDD or dioxin, a toxic gas that is associated with cancer risk and death, as well as other negative health outcomes. Residents in the plume’s path felt the effects immediately, and 19 children were hospitalized with an acne-like skin condition. In the following weeks, about 200 people experienced this condition, and hundreds of residents were evacuated. Many animals and plants in the area died, and to prevent dioxin from reaching the food supply, officials culled thousands of domestic animals. Decontamination efforts lasted years.

After the incident, epidemiological studies revealed that exposure to dioxin is associated with increased risk for cancers and cardiometabolic issues, as well as decreased fertility. In Europe, the event also led to the Seveso Directives: a series of protections and regulations intended to reduce disastrous chemical releases and their impacts. Recent occurrences, such as the Ohio train derailment this year and the subsequent vinyl chloride fire, have highlighted a need to continue focusing on safety around the world.

Brumadinho, Brazil, was flooded by mining waste when a dam operated by Vale broke in 2019.

Credit: Associated Press

Mining and nuclear waste

Separating valuable elements from ores—for example, extracting lithium to develop batteries or refining gold for jewelry—has become increasingly important over the past century, and these activities’ environmental impacts are accumulating. Throughout the 20th century, sequestering mining waste behind dams was widespread. When these tailings dams fail, they can cause devastating floods and environmental damage. A 2019 failure in Brazil, for example, killed 270 people. A 2019 Reuters report classified more than one-third of the world’s tailings dams as posing high risks to nearby communities. Nuclear materials carry additional harms. When uranium and plutonium are refined and used in nuclear power plants or in weapons development, they leave radioactive waste behind, “and we have to deal with it,” Gerald S. Frankel, a materials scientist at the Ohio State University, told C&EN in March 2020. Accidents, such as the deadly 1986 disaster at Chernobyl and the earthquake and tsunami that severely damaged multiple reactors in 2011 at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, further raise the stakes of using nuclear power. A considerable amount of radioactive waste remains dangerous over durations that exceed human life spans, and cleanup efforts can require decades and hundreds of billions of dollars.

Burning fossil fuels emits greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

Credit: Shutterstock

Fossil fuels

Extracting and burning fossil fuels has powered much of the technological progress we associate with modern society and has enabled people to forge connections across the globe. But the products of combustion engines, coal power plants, and petroleum refineries have also caused intense levels of pollution—an outcome too often concentrated in poorer communities. Accumulating studies are revealing the enormous early-death toll of air pollution attributable to fine particulates, nitrogen oxides, and other pollutants produced by combustion. Meanwhile, oil spills and other accidents related to gathering, refining, and transporting these fuels have caused immeasurable environmental damage. On a larger scale, the burning of fossil fuels continues to release carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, driving climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has declared that to prevent catastrophic consequences, we must drastically reduce carbon emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero levels well before the end of the century, but how the world will address this challenge, both technologically and politically, remains to be seen.

Bhopal, 1984

An industrial accident at a Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, wrought death and destruction on a massive scale. A methyl isocyanate tank became dangerously hot and began leaking late on the night of Dec. 2, 1984. As pressure built up in the tank, a safety valve failed, spewing more than 40 metric tons of toxic gas into the air. At least 3,800 people died immediately. Many thousands died later, and tens or even hundreds of thousands were sickened. An estimated half-million people were exposed to the gas. People in the area continue to experience health problems, and concerns about lingering environmental effects remain. Many consider the Bhopal accident to have been the worst industrial disaster in history. “The tragedy at Bhopal still boggles the mind,” C&EN editor Michael Heylin writes in 1994 in an article commemorating the disaster’s 10th anniversary. The tragedy served as a wake-up call for the chemical industry, spurring the widespread adoption of new safety regulations.

DDT

The 1939 discovery that DDT was a powerful insecticide earned Paul Hermann Müller the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Its use quickly grew worldwide because it was so effective at stopping the spread of insect-borne malaria and typhus. But the substance has a massive downside: it becomes concentrated in the food chain and endangers humans and wildlife. DDT disrupts the nervous and endocrine systems and is a likely carcinogen. Although journalists and researchers raised concerns about the chemical as early as the 1940s, Rachel Carson’s landmark 1962 book, Silent Spring, played a key role in revealing how DDT wreaked environmental damage and endangered birds and marine life. Recent research has revealed that DDT’s effects on people extend across generations, to the children and grandchildren of those exposed to the insecticide. DDT was banned in the US in 1972, and its use around the world is limited by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, though it can still be used for malaria control.

Microplastic pollution

Plastics’ convenience, low cost, and durability have made these materials ubiquitous—and disposable. Researchers estimate that most of the 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic produced to date now lies in landfills or ends up in oceans as pollution. After about 75 years of mass-producing plastics, we are awash in tiny pellets of plastic debris less than 5 mm in diameter. Scientists first observed these particles in the 1970s but did not name them microplastics until 2005. Wind and water have carried these plastic pieces to all corners of the earth—the Arctic Ocean and the Antarctic snow, the Andes Mountains, and the deserts of Iran. We consume these particles in table salt, seafood, and the air we breathe. Microplastics’ effects on human health are not yet clear, but studies show that they can build up in the guts of animals and cause internal injuries, as well as boost inflammation. Stemming microplastic pollution starts with reducing production, scientists say. “We have to move away from a throwaway mindset,” environmental physicist Laura Revell of the University of Canterbury told C&EN in February 2022.

Minamata disease, 1950s–60s

Starting in 1932, a Chisso chemical factory producing acetaldehyde in Minamata, Japan, discharged methylmercury into the Minamata Bay. In 1951, the factory changed cocatalysts from manganese dioxide to ferric sulfide and soon also increased the use of a mercuric sulfate catalyst, ratcheting up the volume of discharged methylmercury. Local doctors soon observed a spate of neurological illnesses and began suspecting the area’s seafood as a cause. The first official cases of Minamata disease, including those of two young girls, were reported in 1956. It then took 12 years of research and advocacy for the government to officially name methylmercury pollution as the culprit.

More than 2,000 people from the area were officially diagnosed with Minamata disease, which causes severe neurological symptoms. More than 1,000 of the people with the disease died, and thousands of others likely experienced symptoms. Countries around the world now recognize methylmercury’s severe effects on human health and the environment. In 2013, about 140 nations agreed to the Minamata Convention on Mercury, which was designed to curb the use of mercury in industry.

PFAS

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, have been widely used in industrial and commercial products since the 1940s. These substances, nicknamed forever chemicals, have an impressive ability to repel water, stains, and grease. One early example, Teflon, was serendipitously invented by DuPont in 1938 and marketed after World War II as a nonstick coating for cookware. Today, thousands of PFAS have been synthesized for use in adhesives, construction materials, cleaning products, paints and coatings, cosmetics, textiles, packaging, electronics, explosives, foam fire retardants, and more. In recent decades, however, evidence has emerged from animal and human studies revealing these molecules’ harmful effects. PFAS can cause some cancers, disrupt the endocrine system, and interfere with reproduction and fetal development, as well as have other detrimental effects. Companies have phased out several especially harmful PFAS but are replacing some with new, poorly tested alternatives. Governments are working to develop regulations restricting PFAS production, but these degradation-resistant materials have accumulated widely in the environment—and in our bodies. Although technologies are emerging that can destroy these chemicals, so far there’s no clear path forward for cleaning up PFAS pollution.

Seveso, 1976

On July 10, 1976, near Seveso, Italy, a valve burst at a chemical factory owned by a subsidiary of Roche. The accident released a cloud of 2,3,7,8-tetracholorodibenzo-p-dioxin, known as TCDD or dioxin, a toxic gas that is associated with cancer risk and death, as well as other negative health outcomes. Residents in the plume’s path felt the effects immediately, and 19 children were hospitalized with an acne-like skin condition. In the following weeks, about 200 people experienced this condition, and hundreds of residents were evacuated. Many animals and plants in the area died, and to prevent dioxin from reaching the food supply, officials culled thousands of domestic animals. Decontamination efforts lasted years.

After the incident, epidemiological studies revealed that exposure to dioxin is associated with increased risk for cancers and cardiometabolic issues, as well as decreased fertility. In Europe, the event also led to the Seveso Directives: a series of protections and regulations intended to reduce disastrous chemical releases and their impacts. Recent occurrences, such as the Ohio train derailment this year and the subsequent vinyl chloride fire, have highlighted a need to continue focusing on safety around the world.

Fossil fuels

Extracting and burning fossil fuels has powered much of the technological progress we associate with modern society and has enabled people to forge connections across the globe. But the products of combustion engines, coal power plants, and petroleum refineries have also caused intense levels of pollution—an outcome too often concentrated in poorer communities. Accumulating studies are revealing the enormous early-death toll of air pollution attributable to fine particulates, nitrogen oxides, and other pollutants produced by combustion. Meanwhile, oil spills and other accidents related to gathering, refining, and transporting these fuels have caused immeasurable environmental damage. On a larger scale, the burning of fossil fuels continues to release carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, driving climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has declared that to prevent catastrophic consequences, we must drastically reduce carbon emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero levels well before the end of the century, but how the world will address this challenge, both technologically and politically, remains to be seen.

Mining and nuclear waste

Separating valuable elements from ores—for example, extracting lithium to develop batteries or refining gold for jewelry—has become increasingly important over the past century, and these activities’ environmental impacts are accumulating. Throughout the 20th century, sequestering mining waste behind dams was widespread. When these tailings dams fail, they can cause devastating floods and environmental damage. A 2019 failure in Brazil, for example, killed 270 people. A 2019 Reuters report classified more than one-third of the world’s tailings dams as posing high risks to nearby communities. Nuclear materials carry additional harms. When uranium and plutonium are refined and used in nuclear power plants or in weapons development, they leave radioactive waste behind, “and we have to deal with it,” Gerald S. Frankel, a materials scientist at the Ohio State University, told C&EN in March 2020. Accidents, such as the deadly 1986 disaster at Chernobyl and the earthquake and tsunami that severely damaged multiple reactors in 2011 at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, further raise the stakes of using nuclear power. A considerable amount of radioactive waste remains dangerous over durations that exceed human life spans, and cleanup efforts can require decades and hundreds of billions of dollars.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter