Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Nicole Gaudelli

Genome fixer is developing CRISPR base editors to treat genetic diseases

by Ryan Cross

August 20, 2018 | APPEARED IN VOLUME 96, ISSUE 33

When she was in the fifth grade, Nicole Gaudelli told her father she wanted to become a doctor to help people. He replied, "Why don't you become a scientist?"

"Scientists can help even more people" with their discoveries, she remembers him explaining.

By the time Gaudelli joined Harvard University chemist David Liu's lab as a postdoctoral researcher in 2014, she had published only two scientific papers, but it didn't take long before she invented a tool that could someday treat hundreds, even thousands of diseases.

Soon after Gaudelli arrived, another postdoc, named Alexis Komor, joined the Liu lab with plans to invent a new version of the gene-editing tool CRISPR. The original CRISPR system simply cuts DNA like a pair of scissors, allowing researchers to turn off an errant gene. Komor's so-called base editor worked more like an eraser and pencil, changing a single letter of DNA to another—a cytidine (C) to a thymidine (T).

While assisting Komor with the experiment, Gaudelli began planning a second base editor to swap DNA's other two letters, adenosine (A) and guanosine (G).

Gaudelli's proposed adenine base editor could theoretically fix nearly 50% of the single-letter DNA mutations known to cause disease in humans, accounting for thousands of genetic diseases. But while Komor's editor was built by combining existing proteins, Gaudelli's version required evolving a protein to perform a chemical reaction that doesn't exist in nature.

That broke an 18-year-old Liu lab rule to avoid projects in which the first step requires evolving the starting material. "Honestly, I thought it was never going to work," Gaudelli says. "But the technology's potential was so overwhelmingly high that it was worth it."

After a year of tenacious work, Gaudelli was successful. She spent an additional year refining the base editor before publishing the results. Then Harvard licensed the base editors to a new biotech start-up called Beam Therapeutics, which Liu cofounded.

Remembering her conversation with her father, Gaudelli decided to forgo her plans to join academia and instead joined Beam to help transform her invention into a medicine for treating genetic diseases.

"It's classic Nicole," Liu says. "Making sure the fruits of her labor actually help others and don't just end up on the pages of a journal."

Watch Gaudelli speak at the American Chemical Society national meeting on Aug. 20 in Boston.

Vitals

Current affiliation: Beam Therapeutics

Age: 33

Ph.D. alma mater: Johns Hopkins University

Role model: My father. When I was a little girl, my dad and I spent hours on the weekend creating mini chemistry experiments such as growing crystals, exploding volcanoes, and even making nylon. I learned from my father that challenges can be overcome (scientific or not) if we are thoughtful about the questions we ask, test our hypothesis, and are critical about the outcomes.

If I weren't a chemist, I would be: A doggy hotel and spa owner, and I would establish an animal adoption center.

Latest TV show binge-watched: "Mozart in the Jungle"

Walk-up song: "My Shot" from the "Hamilton" soundtrack

Research at a glance

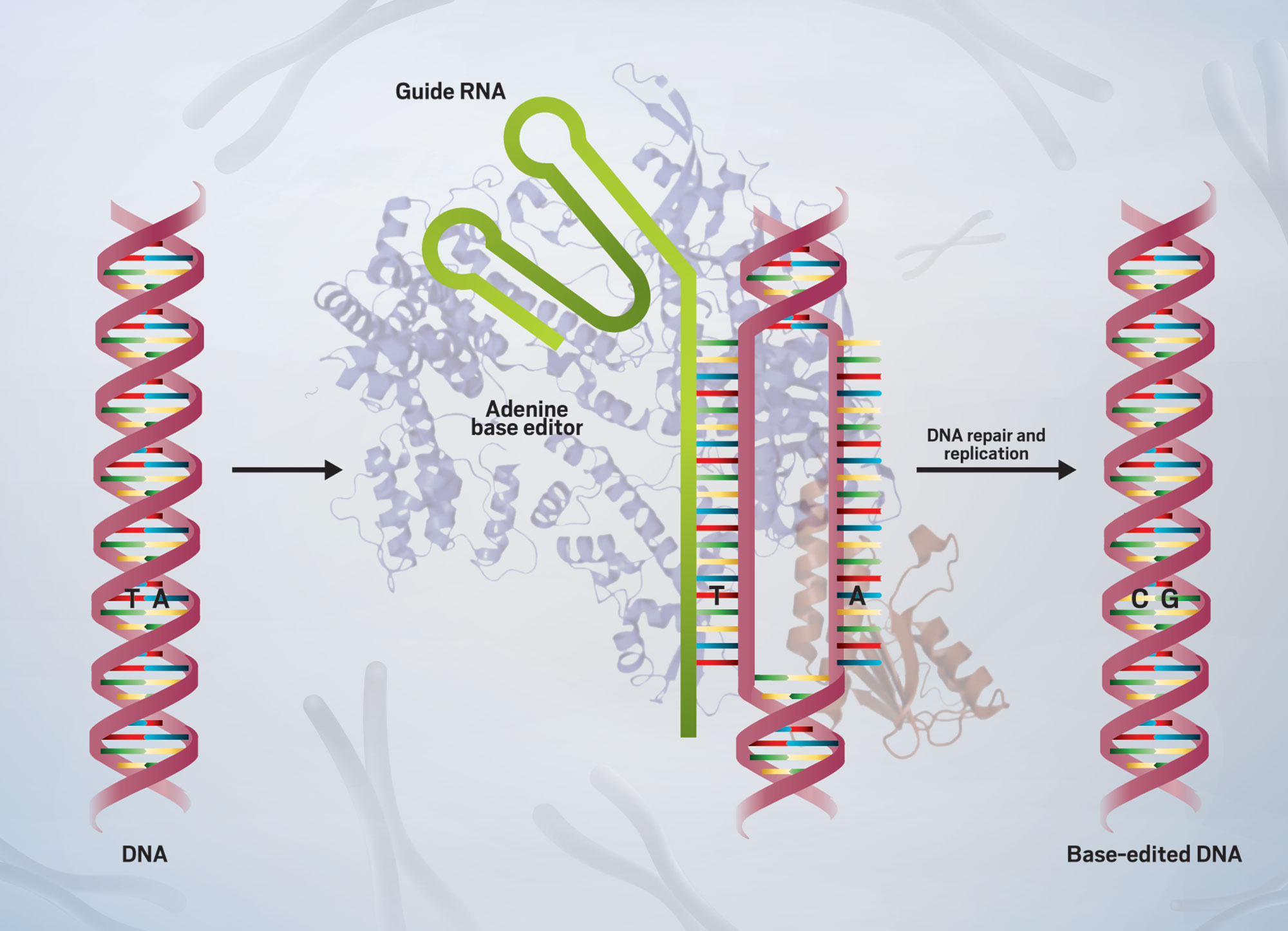

Credit: David Liu/Yang H. Ku/C&EN/Shutterstock

To precisely fix disease-causing mutations, Gaudelli designed an adenine base editor that can swap individual bases of DNA. It includes an impaired Cas9 enzyme and guide RNA to direct the editor to a specific DNA site. Through a series of steps, the base editor and the cell's repair machinery swap an A:T base pair for a G:C base pair.

Rare Disease

Amazing Women

Nicole Gaudelli

Genome fixer is developing CRISPR base editors to treat genetic diseases

by Ryan Cross

August 19, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 33

Vitals

Current affiliation: Beam Therapeutics

Age: 33

Ph.D. alma mater: Johns Hopkins University

Role model: My father. When I was a little girl, my dad and I spent hours on the weekend creating mini chemistry experiments such as growing crystals, exploding volcanoes, and even making nylon. I learned from my father that challenges can be overcome (scientific or not) if we are thoughtful about the questions we ask, test our hypothesis, and are critical about the outcomes.

If I weren’t a chemist, I would be: A doggy hotel and spa owner, and I would establish an animal adoption center.

Latest TV show binge-watched: “Mozart in the Jungle”

Walk-up song: “My Shot” from the “Hamilton” soundtrack

Three key papers

“Programmable Base Editing of A•T to G•C in Genomic DNA without DNA Cleavage” (Nature 2017, DOI: 10.1038/nature24644)

“Programmable Editing of a Target Base in Genomic DNA without Double-Stranded DNA Cleavage” (Nature 2016, DOI: 10.1038/nature17946)

“β-Lactam Formation by a Non-ribosomal Peptide Synthetase during Antibiotic Biosynthesis” (Nature 2015, DOI: 10.1038/nature14100)

Stories in C&EN about Nicole Gaudelli’s work

“Inventor, Chemist, and CRISPR Craftsman: Inside David Liu’s Evolution Workshop”

“David Liu Launches Beam Therapeutics to Treat Genetic Diseases with CRISPR Base Editing”

“Adenine Base Editor Excels at Fixing Point Mutations”

“Improved Route to Single-Base Genome Editing”

When she was in the fifth grade, Nicole Gaudelli told her father she wanted to become a doctor to help people. He replied, “Why don’t you become a scientist?”

“Scientists can help even more people” with their discoveries, she remembers him explaining.

By the time Gaudelli joined Harvard University chemist David Liu’s lab as a postdoctoral researcher in 2014, she had published only two scientific papers, but it didn’t take long before she invented a tool that could someday treat hundreds, even thousands of diseases.

Soon after Gaudelli arrived, another postdoc, named Alexis Komor, joined the Liu lab with plans to invent a new version of the gene-editing tool CRISPR. The original CRISPR system simply cuts DNA like a pair of scissors, allowing researchers to turn off an errant gene. Komor’s so-called base editor worked more like an eraser and pencil, changing a single letter of DNA to another—a cytidine (C) to a thymidine (T).

While assisting Komor with the experiment, Gaudelli began planning a second base editor to swap DNA’s other two letters, adenosine (A) and guanosine (G).

Gaudelli’s proposed adenine base editor could theoretically fix nearly 50% of the single-letter DNA mutations known to cause disease in humans, accounting for thousands of genetic diseases. But while Komor’s editor was built by combining existing proteins, Gaudelli’s version required evolving a protein to perform a chemical reaction that doesn’t exist in nature.

That broke an 18-year-old Liu lab rule to avoid projects in which the first step requires evolving the starting material. “Honestly, I thought it was never going to work,” Gaudelli says. “But the technology’s potential was so overwhelmingly high that it was worth it.”

After a year of tenacious work, Gaudelli was successful. She spent an additional year refining the base editor before publishing the results. Then Harvard licensed the base editors to a new biotech start-up called Beam Therapeutics, which Liu cofounded.

Remembering her conversation with her father, Gaudelli decided to forgo her plans to join academia and instead joined Beam to help transform her invention into a medicine for treating genetic diseases.

“It’s classic Nicole,” Liu says. “Making sure the fruits of her labor actually help others and don’t just end up on the pages of a journal.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter