Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Computational Chemistry

Osvaldo Gutierrez

Organic polymath is coaxing tricky metals into helping forge carbon-carbon bonds

by Sam Lemonick

August 14, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 31

Credit: Osvaldo Gutierrez/University of Maryland (Gutierrez); Jynto/Wikimedia Commons (structure); Shutterstock (numbers, element, pills)

Chemists often reach for transition-metal catalysts when they need to add hard-to-make bonds, like carbon-carbon bonds, to a molecule. But the best of these catalysts use expensive metals such as palladium, and that drives up the price of the molecules made in these reactions.

Osvaldo Gutierrez thinks he can find ways to use cheap, abundant iron to make those same bonds and bring down the cost of lifesaving drug molecules. A professor at the University of Maryland, Gutierrez experienced firsthand the difference cancer drugs made in the last years of his mother’s life. “I saw her pain before taking those medicines,” he says. “I can only imagine how many people around the world are going through that because they don’t have access to those medicines.”

Advertisement

Gutierrez brings a rare set of skills to bear for understanding these catalytic reactions. “He is unique in being an outstanding computational and experimental chemist at the same time,” says University of California, Los Angeles, chemist Kendall Houk, who mentored Gutierrez when he was an undergraduate.

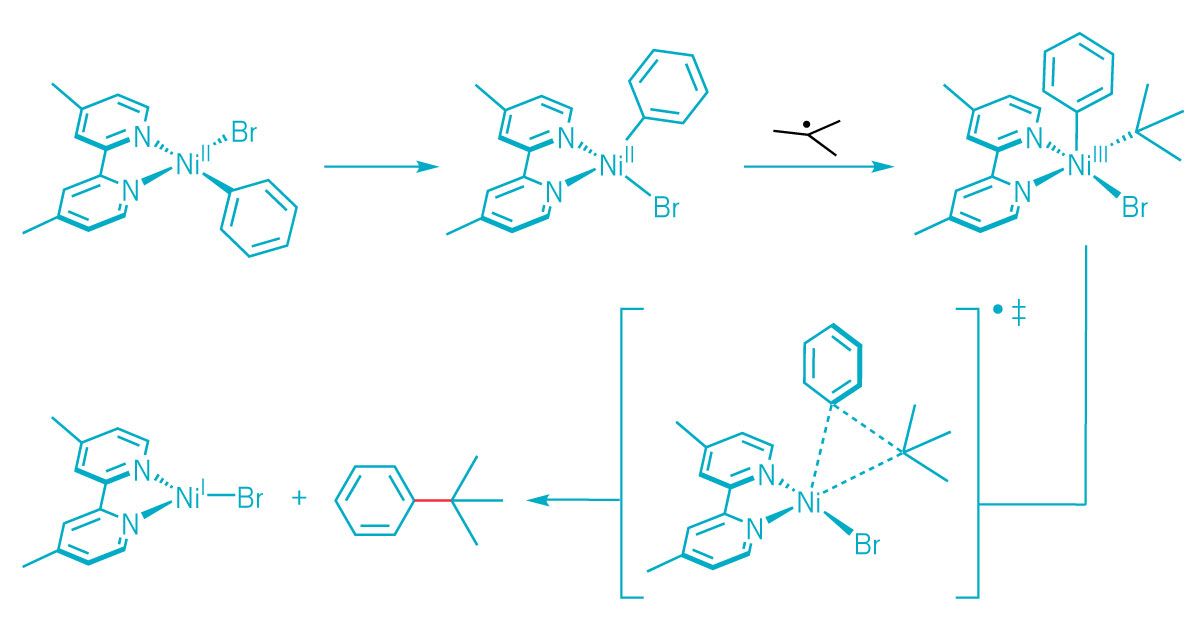

That’s good, because iron is not an easy metal to model. Multiple oxidation states, radicals, and complex electron interactions make iron complexes difficult to simulate accurately. University of Pennsylvania chemist Gary Molander, who has collaborated with Gutierrez on reactions catalyzed by another tricky metal, nickel, says even the highest-profile computational chemists “don’t want to touch the stuff Osvaldo does.”

Not only can Gutierrez and his group chart the fine details of these catalytic mechanisms, they can use that knowledge to develop new reactions, like making new carbon-carbon bonds on unactivated alkenes. His secret is to be fearless. “I tell my students we’re going to be tackling things that are very challenging, but we’re going to provide unique information to the world,” he says.

Getting to where he is now—a tenure-track professor at a large, research-focused university with papers in top journals—is a feat for any scientist. Still, Gutierrez’s path has been longer and steeper than most.

He came to the US from Mexico as an undocumented immigrant when he was 9. Gutierrez ran a construction business and nearly became a professional boxer, all before he graduated high school.

Without legal status, Gutierrez found many closed doors. His childhood dream of becoming a doctor disintegrated when no medical school would admit him. He discovered a love for synthetic chemistry under Houk, but avoided lab work for fear an accident could endanger him or his department legally. He didn’t learn the skills of experimental chemistry until his postdoctoral studies at the University of Pennsylvania, after gaining legal status in 2012 through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Since his time at Penn, Gutierrez has been working with the Alliance for Diversity in Science and Engineering to create opportunities and build community for underrepresented people in chemistry. It’s one way that he can now play a role he sees as having been vital to his success: that of a mentor. “I could easily have fallen into the cracks,” he says, if not for his mentors along the way.

And as for his plan to be a doctor? Gutierrez isn’t upset anymore: “If I knew what a research professor was, I would have chosen it all my life.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: University of Maryland

Age: 36

PhD alma mater: University of California, Davis

Hometown: Salamanca, Mexico

If I weren’t a chemist, I’d be: A boxer. “When I was young I dreamed of becoming the next Julio César Chávez!”

If I were an element, I’d be: Iron. “It’s everywhere, has a lot of untapped potential in chemical synthesis, and often scares computational chemists!”

Chemists often reach for transition-metal catalysts when they need to add hard-to-make bonds, like carbon-carbon bonds, to a molecule. But the best of these catalysts use expensive metals such as palladium, and that drives up the price of the molecules made in these reactions.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: University of Maryland

▸ Age: 36

▸ PhD alma mater: University of California, Davis

▸ Hometown: Salamanca, Mexico

▸ If I weren’t a chemist, I’d be: A boxer. “When I was young I dreamed of becoming the next Julio César Chávez!”

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: Iron. “It’s everywhere, has a lot of untapped potential in chemical synthesis, and often scares computational chemists!”

Osvaldo Gutierrez thinks he can find ways to use cheap, abundant iron to make those same bonds and bring down the cost of lifesaving drug molecules. A professor at the University of Maryland, Gutierrez experienced firsthand the difference cancer drugs made in the last years of his mother’s life. “I saw her pain before taking those medicines,” he says. “I can only imagine how many people around the world are going through that because they don’t have access to those medicines.”

Gutierrez brings a rare set of skills to bear for understanding these catalytic reactions. “He is unique in being an outstanding computational and experimental chemist at the same time,” says University of California, Los Angeles, chemist Kendall Houk, who mentored Gutierrez when he was an undergraduate.

That’s good, because iron is not an easy metal to model. Multiple oxidation states, radicals, and complex electron interactions make iron complexes difficult to simulate accurately. University of Pennsylvania chemist Gary Molander, who has collaborated with Gutierrez on reactions catalyzed by another tricky metal, nickel, says even the highest-profile computational chemists “don’t want to touch the stuff Osvaldo does.”

Not only can Gutierrez and his group chart the fine details of these catalytic mechanisms, they can use that knowledge to develop new reactions, like making new carbon-carbon bonds on unactivated alkenes. His secret is to be fearless. “I tell my students we’re going to be tackling things that are very challenging, but we’re going to provide unique information to the world,” he says.

Getting to where he is now—a tenure-track professor at a large, research-focused university with papers in top journals—is a feat for any scientist. Still, Gutierrez’s path has been longer and steeper than most.

He came to the US from Mexico as an undocumented immigrant when he was 9. Gutierrez ran a construction business and nearly became a professional boxer, all before he graduated high school.

Without legal status, Gutierrez found many closed doors. His childhood dream of becoming a doctor disintegrated when no medical school would admit him. He discovered a love for synthetic chemistry under Houk, but avoided lab work for fear an accident could endanger him or his department legally. He didn’t learn the skills of experimental chemistry until his postdoctoral studies at the University of Pennsylvania, after gaining legal status in 2012 through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Since his time at Penn, Gutierrez has been working with the Alliance for Diversity in Science and Engineering to create opportunities and build community for underrepresented people in chemistry. It’s one way that he can now play a role he sees as having been vital to his success: that of a mentor. “I could easily have fallen into the cracks,” he says, if not for his mentors along the way.

And as for his plan to be a doctor? Gutierrez isn’t upset anymore: “If I knew what a research professor was, I would have chosen it all my life.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter