Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

Cesunica Ivey

Air quality crusader is gathering information about our daily exposures to dangerous emissions

by Katherine Bourzac

August 20, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 30

Credit: UC Riverside (Ivey); Shutterstock (nitrogen dioxide, trucks); courtesy of Cesunica Ivey (Heat map)

Do you know what level of air pollution you’re exposed to at work? Or while cooking dinner, or driving with the windows down? Though the stakes for our health are high, says Cesunica Ivey, most people can’t answer these questions. Ivey, an environmental and chemical engineer at the University of California, Berkeley, is developing techniques for air quality monitoring and modeling in the hopes of changing that.

Exposure to air pollution causes and exacerbates respiratory and cardiovascular disease and kills about 7 million people globally every year, according to the World Health Organization. Since the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, ambient air quality in the US has improved. Ivey is one of a group of researchers who want to go further by finding point sources and individual exposures that affect people’s health but that might not appear in regional averages. Ivey is devising solutions to curb those exposures.

Advertisement

“What are the best strategies for mitigation from an individual point of view? Which microenvironments pose the most risk? We have no idea. And everyone should have that information,” she says.

Ivey designs studies that can tease out the air quality impact of specific sources, such as traffic or a warehouse or a power plant, and “that has real implications for environmental justice,” says Armistead Russell, who was Ivey’s PhD adviser at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He says Ivey is becoming “one of the leading voices looking at and solving excess air pollution exposures within vulnerable communities.”

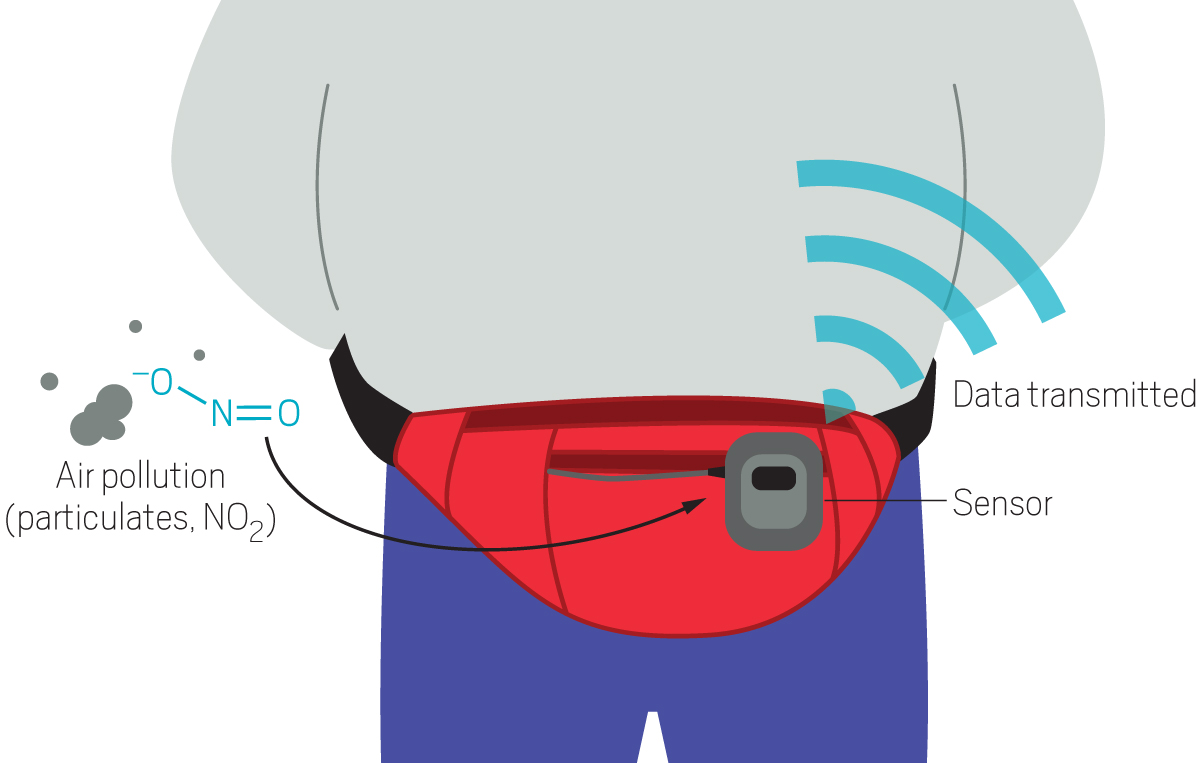

Ivey started her lab in 2018 at the University of California, Riverside, in the region with the highest concentration of warehouses and the worst air quality in the US. Seeing the conditions in Southern California inspired her to unite work on ambient air pollution with work on indoor air pollution. She’s combining chemical transport models, ambient air quality information, readings from wearable pollution sensors, GPS data, and other methods to better understand individuals’ exposure to air pollution and, she hopes, to mitigate it.

This year, she published a pilot study that combined GPS data and readings from wearable air pollution sensors to see how individuals’ exposures changed as they moved throughout the day in inland Southern California. The project, she says, shows that these kinds of personalized measurements “can be really informative to understand short-term air pollution risk” and how these risks are correlated with race, ethnicity, and income. The pilot study found that participants with lower socioeconomic status were exposed to more air pollution in their homes from sources such as inefficient heaters or cookstoves than were other participants. Ivey says this type of study can highlight sources that regulators might tackle, as well as pollution hot spots that might be good places for government or community groups to install continuous air quality monitors.

Ivey’s current project expands on this pilot. She’s mapping out how a person’s day-to-day physical proximity to known sources of air pollution, such as a rail yard, contributes to their daily air pollution exposures.

The goal is not to have everyone carry around an air pollution monitor but to equip the public with more personalized air quality forecasts. Just like your weather app might prompt you to throw an umbrella in your bag, a more personalized air quality forecast could help, for example, someone with asthma decide to avoid an area or to wear a respirator.

That’s a grand vision, one she’s already putting to the test. Ivey is planning a study of whether personalized exposure predictions can affect how people respond to forecasts about wildfire smoke—a growing air quality problem in much of the western US.

“I want to help people make their own, more informed decisions,” she says. “I’m thinking about this from a human point of view.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: University of California, Berkeley

Age: 33

PhD alma mater: Georgia Institute of Technology

Hometown: Atlanta

If I were an element, I’d be: Potassium. “It provides critical functioning for bodily processes and is quite malleable in its solid phase. Similarly, I strive to add value to any situation I am part of and serve in roles that support the functioning of my team or organization while also being flexible and adapting to change when needed.”

Role model: “Oprah Winfrey. She has achieved so much success although the odds were stacked against her. She maintains poise and grace in the face of challenges, and she created a life and career that reflects her own unique vision of success.”

Do you know what level of air pollution you’re exposed to at work? Or while cooking dinner, or driving with the windows down? Though the stakes for our health are high, says Cesunica Ivey, most people can’t answer these questions. Ivey, an environmental and chemical engineer at the University of California, Berkeley, is developing techniques for air quality monitoring and modeling in the hopes of changing that.

Exposure to air pollution causes and exacerbates respiratory and cardiovascular disease and kills about 7 million people globally every year, according to the World Health Organization. Since the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, ambient air quality in the US has improved. Ivey is one of a group of researchers who want to go further by finding point sources and individual exposures that affect people’s health but that might not appear in regional averages. Ivey is devising solutions to curb those exposures.

“What are the best strategies for mitigation from an individual point of view? Which microenvironments pose the most risk? We have no idea. And everyone should have that information,” she says.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: University of California, Berkeley

▸ Age: 33

▸ PhD alma mater: Georgia Institute of Technology

▸ Hometown: Atlanta

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: Potassium. “It provides critical functioning for bodily processes and is quite malleable in its solid phase. Similarly, I strive to add value to any situation I am part of and serve in roles that support the functioning of my team or organization while also being flexible and adapting to change when needed.”

▸ Role model: “Oprah Winfrey. She has achieved so much success although the odds were stacked against her. She maintains poise and grace in the face of challenges, and she created a life and career that reflects her own unique vision of success.”

Ivey designs studies that can tease out the air quality impact of specific sources, such as traffic or a warehouse or a power plant, and “that has real implications for environmental justice,” says Armistead Russell, who was Ivey’s PhD adviser at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He says Ivey is becoming “one of the leading voices looking at and solving excess air pollution exposures within vulnerable communities.”

Ivey started her lab in 2018 at the University of California, Riverside, in the region with the highest concentration of warehouses and the worst air quality in the US. Seeing the conditions in Southern California inspired her to unite work on ambient air pollution with work on indoor air pollution. She’s combining chemical transport models, ambient air quality information, readings from wearable pollution sensors, GPS data, and other methods to better understand individuals’ exposure to air pollution and, she hopes, to mitigate it.

This year, she published a pilot study that combined GPS data and readings from wearable air pollution sensors to see how individuals’ exposures changed as they moved throughout the day in inland Southern California. The project, she says, shows that these kinds of personalized measurements “can be really informative to understand short-term air pollution risk” and how these risks are correlated with race, ethnicity, and income. The pilot study found that participants with lower socioeconomic status were exposed to more air pollution in their homes from sources such as inefficient heaters or cookstoves than were other participants. Ivey says this type of study can highlight sources that regulators might tackle, as well as pollution hot spots that might be good places for government or community groups to install continuous air quality monitors.

Ivey’s current project expands on this pilot. She’s mapping out how a person’s day-to-day physical proximity to known sources of air pollution, such as a rail yard, contributes to their daily air pollution exposures.

The goal is not to have everyone carry around an air pollution monitor but to equip the public with more personalized air quality forecasts. Just like your weather app might prompt you to throw an umbrella in your bag, a more personalized air quality forecast could help, for example, someone with asthma decide to avoid an area or to wear a respirator.

That’s a grand vision, one she’s already putting to the test. Ivey is planning a study of whether personalized exposure predictions can affect how people respond to forecasts about wildfire smoke—a growing air quality problem in much of the western US.

“I want to help people make their own, more informed decisions,” she says. “I’m thinking about this from a human point of view.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter