Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Jesús Velázquez

Catalyst connoisseur is studying materials that could mitigate climate change or clean up water

by Jessica Marshall

August 20, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 30

Credit: NASA Harrient G. Jenkins Fellowship Program (VELÁZQUEZ); Justin L. Andrews (polyhedra); Brian Wuille Bille (micrographs)

The motivation for Jesús Velázquez’s career took root growing up in Puerto Rico, where hurricanes were an annual threat. “Every year there was going to be the chance of not having access to clean water and being at the mercy of a very vulnerable electrical grid,” he says. “Knowing how it feels to not have an immediate solution for a problem like that and how it impacted my community, I think it really planted the seed that if I ever had the opportunity to be of service, that would be a dream come true.”

During his undergraduate years at the University of Puerto Rico in Cayey, Velázquez sought a campus job that would give him more opportunity to study than his side jobs in construction and retail offered. He became a chemistry tutor after he found himself explaining chemistry concepts to others. “I don’t know why; chemistry clicked,” he says. “It seemed that chemistry was giving me this platform not only to help explain fundamentally interesting phenomena but also to connect with people.”

Advertisement

Fast-forward through an industrial job out of college, his PhD at the University at Buffalo, and a postdoctoral fellowship at the California Institute of Technology, and Velázquez’s dream has come true. As an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, Velázquez uses chemistry to try to solve those problems he faced again and again in childhood: access to energy and clean water.

Velázquez focuses on electrochemical catalysis—designing materials that can speed up chemical reactions that produce or are driven by electricity. He combines theoretical predictions with chemical intuition to develop and characterize materials that could help address climate change or that could help remove contaminants from water.

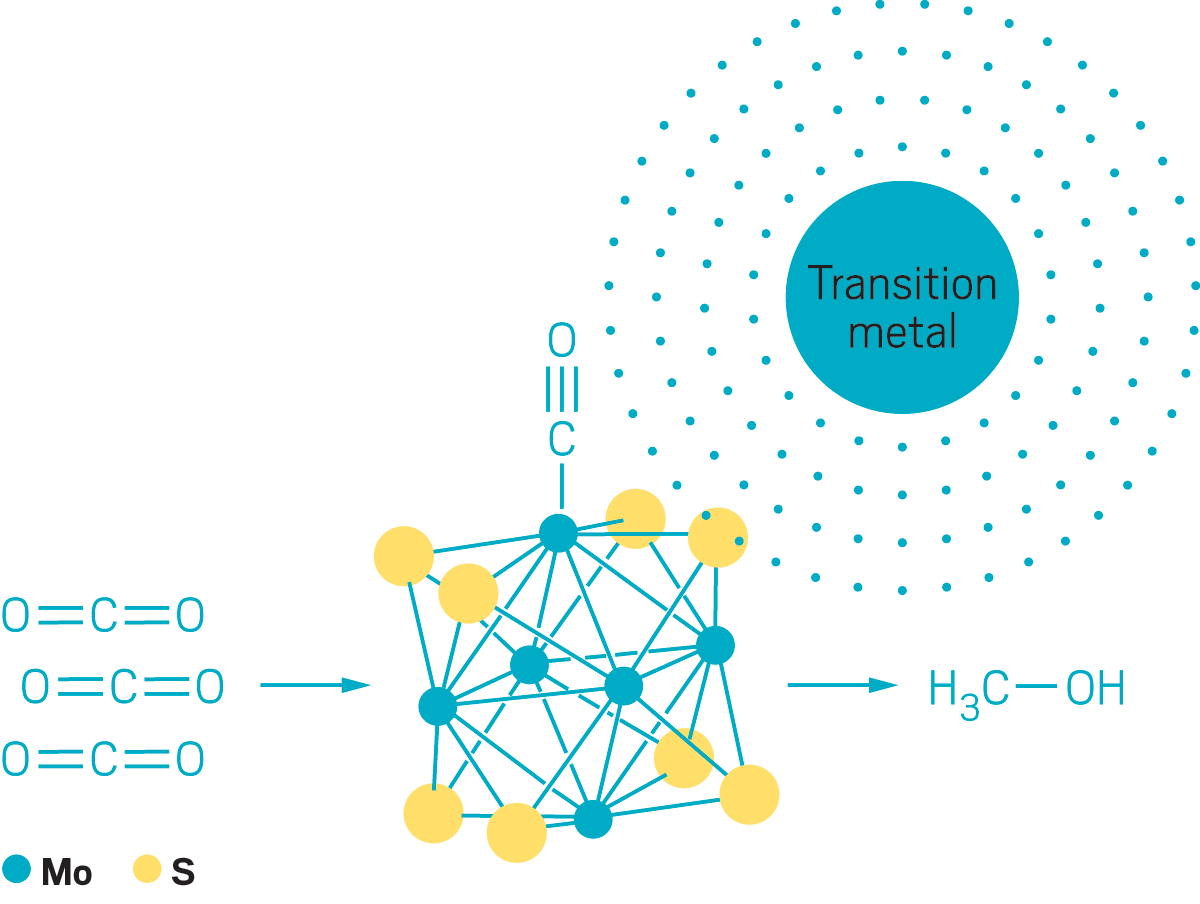

These materials include metal chalcogens, such as Mo6S8, a solid with an octahedral network of molybdenum interlaced with a cube of sulfur. The sulfur atoms in Mo6S8 can create an extended structure, Velázquez says, with cavities just right for filling with transition elements or other species that create catalytic sites for carrying out chemical transformations.

Velázquez’s work shows that these materials can be useful for turning the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into methanol, offering a strategy for removing it from the atmosphere and converting it into fuel. His lab was able to tweak how key intermediates in the electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to methanol behave within these materials. That work gave the group a tool for trying to more effectively get rid of CO2, Velázquez says. “We were able to experimentally show that this electrochemical reactivity to produce methanol is accessible” through these materials, he says. He has built on this finding, showing that a basic “hot-pocket microwave,” as he calls it, can create new materials for catalysis. In another vein of his research, he has built novel materials that grab contaminants like crude oil or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from water across a range of pHs.

“As a chemist, he has had some amazing success,” says Sarbajit Banerjee, Velázquez’s PhD adviser, now at Texas A&M University. But Banerjee also points to Velázquez’s accomplishments beyond research: “He has just continued to give back.” Velázquez has recruited a stream of young scientists from Puerto Rico and from historically Black colleges and universities, and he has offered an academic home to many first-generation students. “He believes that chemistry has to be more inclusive, that we have this incredible talent we have to tap into,” Banerjee says.

Velázquez says he hopes to transform how chemists train students so that chemists better support the needs of the next generation of scientists and to retain those who might look at academia and think it’s not for them. “I have the belief that rigor and empathy can coexist,” he says.

Vitals

Current affiliation: University of California, Davis

Age: 41

PhD alma mater: University at Buffalo

Hometown: Juncos, Puerto Rico

If I were an element, I’d be: Tungsten. “It isn’t flashy like fluorine and cesium, but it has great tensile strength, and it’s extremely difficult to melt, corrode, or break down, and I like to relate that to my own perseverance and tenacity.”

Role model: “I was raised by a bevy of fierce women constituted by my mother, aunt, grandmother, and great-grandmother. They all played pivotal roles in my upbringing, and in the face of all of their own life challenges and lack of formal education, they always found a way to support my learning—instilling the value of persistence and optimism along the way.”

The motivation for Jesús Velázquez’s career took root growing up in Puerto Rico, where hurricanes were an annual threat. “Every year there was going to be the chance of not having access to clean water and being at the mercy of a very vulnerable electrical grid,” he says. “Knowing how it feels to not have an immediate solution for a problem like that and how it impacted my community, I think it really planted the seed that if I ever had the opportunity to be of service, that would be a dream come true.”

During his undergraduate years at the University of Puerto Rico in Cayey, Velázquez sought a campus job that would give him more opportunity to study than his side jobs in construction and retail offered. He became a chemistry tutor after he found himself explaining chemistry concepts to others. “I don’t know why; chemistry clicked,” he says. “It seemed that chemistry was giving me this platform not only to help explain fundamentally interesting phenomena but also to connect with people.”

Fast-forward through an industrial job out of college, his PhD at the University at Buffalo, and a postdoctoral fellowship at the California Institute of Technology, and Velázquez’s dream has come true. As an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, Velázquez uses chemistry to try to solve those problems he faced again and again in childhood: access to energy and clean water.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: University of California, Davis

▸ Age: 41

▸ PhD alma mater: University at Buffalo

▸ Hometown: Juncos, Puerto Rico

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: Tungsten. “It isn’t flashy like fluorine and cesium, but it has great tensile strength, and it’s extremely difficult to melt, corrode, or break down, and I like to relate that to my own perseverance and tenacity.”

▸ Role model: “I was raised by a bevy of fierce women constituted by my mother, aunt, grandmother, and great-grandmother. They all played pivotal roles in my upbringing, and in the face of all of their own life challenges and lack of formal education, they always found a way to support my learning—instilling the value of persistence and optimism along the way.”

Velázquez focuses on electrochemical catalysis—designing materials that can speed up chemical reactions that produce or are driven by electricity. He combines theoretical predictions with chemical intuition to develop and characterize materials that could help address climate change or that could help remove contaminants from water.

These materials include metal chalcogens, such as Mo6S8, a solid with an octahedral network of molybdenum interlaced with a cube of sulfur. The sulfur atoms in Mo6S8 can create an extended structure, Velázquez says, with cavities just right for filling with transition elements or other species that create catalytic sites for carrying out chemical transformations.

Velázquez’s work shows that these materials can be useful for turning the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into methanol, offering a strategy for removing it from the atmosphere and converting it into fuel. His lab was able to tweak how key intermediates in the electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to methanol behave within these materials. That work gave the group a tool for trying to more effectively get rid of CO2, Velázquez says. “We were able to experimentally show that this electrochemical reactivity to produce methanol is accessible” through these materials, he says. He has built on this finding, showing that a basic “hot-pocket microwave,” as he calls it, can create new materials for catalysis. In another vein of his research, he has built novel materials that grab contaminants like crude oil or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from water across a range of pHs.

“As a chemist, he has had some amazing success,” says Sarbajit Banerjee, Velázquez’s PhD adviser, now at Texas A&M University. But Banerjee also points to Velázquez’s accomplishments beyond research: “He has just continued to give back.” Velázquez has recruited a stream of young scientists from Puerto Rico and from historically Black colleges and universities, and he has offered an academic home to many first-generation students. “He believes that chemistry has to be more inclusive, that we have this incredible talent we have to tap into,” Banerjee says.

Velázquez says he hopes to transform how chemists train students so that chemists better support the needs of the next generation of scientists and to retain those who might look at academia and think it’s not for them. “I have the belief that rigor and empathy can coexist,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter