Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Alaaeddin Alsbaiee

Polymer pro is smoothing the way to superior silicon data storage

by Craig Bettenhausen

August 20, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 30

Credit: DuPont (Alsbaiee); Shutterstock (circuit boards, glass)

What do water filters, wind turbine blades, and semiconductor polishing pads have in common? Polymer chemistry—and big contributions from Alaaeddin Alsbaiee. To get that kind of breadth at 38 years old, you have to start early.

“I’ve liked chemistry since I was a kid. I had some test tubes and Erlenmeyers in my bedroom,” Alsbaiee says. The tools were gifts from his uncle, an organic chemist who worked for the food and drink company Nestlé. The 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Ahmed Zewail—the first person from the Arabic-speaking world to win the honor—galvanized Alsbaiee’s desire to become a scientist. So when Alsbaiee started at Syria’s Damascus University the next year, he picked a chemistry major.

Advertisement

As his education took him around the world from Syria to Saudi Arabia, Canada, and the US, he developed a systematic approach to science that his peers say has led to a lot of great ideas and innovations.

During his postdoc with William Dichtel at Cornell University, Alsbaiee pioneered a new class of high-surface-area cyclodextrin polymers that could remove hundreds of organic pollutants, including difficult-to-catch per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), from the air and water. PFAS are used in nonstick coatings, lubricants, and other applications, but they persist in the environment—a property that has earned them the nickname “forever chemicals”—and have been linked to cancer and other health risks. In 2016, Alsbaiee’s research laid the groundwork for a company, Cyclopure, to commercialize the technology, Dichtel says.

Later, at Arkema, Alsbaiee worked on the team that developed Elium, a tough thermoplastic resin that the firm says will enable the creation of the first recyclable wind turbine blades, removing a major environmental downside from the promising renewable energy source.

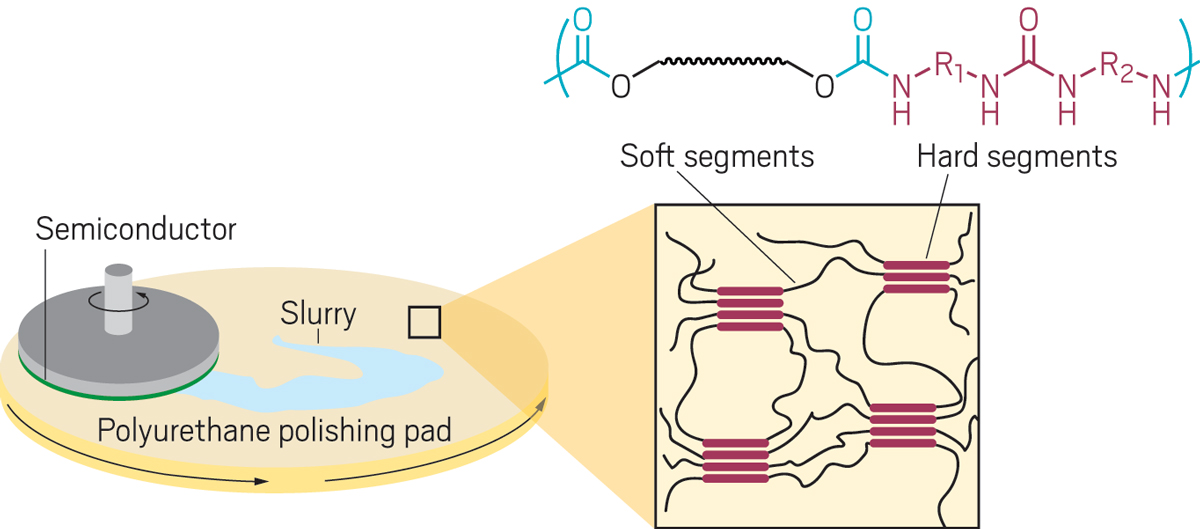

Now at DuPont, Alsbaiee is developing new types of polyurethane block copolymers for use in semiconductor polishing pads. The topic might sound prosaic, but such polishing, known as chemical-mechanical planarization (CMP), is critical to modern electronics. The process gives circuit boards an exquisitely flat surface, which allows accurate printing of the tiny, micrometer-scale features that the chips in the next generation of devices will demand. A new family of CMP pads that Alsbaiee coinvented will go on the market next year.

A new project for Alsbaiee begins with a month or more away from the bench. He starts with books on the topic, then reads reviews, and then digs down into research papers. As he goes, he summarizes everything he reads in a series of spreadsheets. His next step is to analyze those spreadsheets to identify gaps that he might fill.

The next part is his favorite, Alsbaiee says. He brings in collaborators to brainstorm ideas and score them on their synthetic difficulty, time commitment required, sustainability, scalability, and safety, as well as the availability and cost of materials.

Bryan Barton, who until recently led the CMP group at DuPont, says that an astonishing amount of planning and preparation set Alsbaiee apart early from other chemists—and paid off. “Alaaeddin focused on providing easily scalable and sustainable solutions, which are currently being developed into breakthrough products and will have an impact in the broader specialty polymer community,” Barton says.

Alsbaiee would eventually like to apply his system in a research leadership role. “I like to think about the strategic side of R&D projects,” he says. He’s also interested in building up the chemistry community. For example, since 2019, he has volunteered to translate some C&EN articles into Arabic with the goal of broadening access to science communication. He says the Arabic world is “eager to know more about science, about recent discoveries around the world and the exciting technologies that are being developed.”

Vitals

Current affiliation: DuPont

Age: 38

PhD alma mater: University of Alberta

Hometown: Damascus, Syria

If I were an element, I’d be: Carbon. “It’s versatile and it has the right size and electronic configuration to form billions of organic molecules with boundless forms and sizes.”

Role model: “Ahmed Zewail. He is the father of femtochemistry, and he was the first Arab scientist to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.”

What do water filters, wind turbine blades, and semiconductor polishing pads have in common? Polymer chemistry—and big contributions from Alaaeddin Alsbaiee. To get that kind of breadth at 38 years old, you have to start early.

“I’ve liked chemistry since I was a kid. I had some test tubes and Erlenmeyers in my bedroom,” Alsbaiee says. The tools were gifts from his uncle, an organic chemist who worked for the food and drink company Nestlé. The 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Ahmed Zewail—the first person from the Arabic-speaking world to win the honor—galvanized Alsbaiee’s desire to become a scientist. So when Alsbaiee started at Syria’s Damascus University the next year, he picked a chemistry major.

As his education took him around the world from Syria to Saudi Arabia, Canada, and the US, he developed a systematic approach to science that his peers say has led to a lot of great ideas and innovations.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: DuPont

▸ Age: 38

▸ PhD alma mater: University of Alberta

▸ Hometown: Damascus, Syria

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: Carbon. “It’s versatile and it has the right size and electronic configuration to form billions of organic molecules with boundless forms and sizes.”

▸ Role model: “Ahmed Zewail. He is the father of femtochemistry, and he was the first Arab scientist to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.”

During his postdoc with William Dichtel at Cornell University, Alsbaiee pioneered a new class of high-surface-area cyclodextrin polymers that could remove hundreds of organic pollutants, including difficult-to-catch per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), from the air and water. PFAS are used in nonstick coatings, lubricants, and other applications, but they persist in the environment—a property that has earned them the nickname “forever chemicals”—and have been linked to cancer and other health risks. In 2016, Alsbaiee’s research laid the groundwork for a company, Cyclopure, to commercialize the technology, Dichtel says.

Later, at Arkema, Alsbaiee worked on the team that developed Elium, a tough thermoplastic resin that the firm says will enable the creation of the first recyclable wind turbine blades, removing a major environmental downside from the promising renewable energy source.

Now at DuPont, Alsbaiee is developing new types of polyurethane block copolymers for use in semiconductor polishing pads. The topic might sound prosaic, but such polishing, known as chemical-mechanical planarization (CMP), is critical to modern electronics. The process gives circuit boards an exquisitely flat surface, which allows accurate printing of the tiny, micrometer-scale features that the chips in the next generation of devices will demand. A new family of CMP pads that Alsbaiee coinvented will go on the market next year.

A new project for Alsbaiee begins with a month or more away from the bench. He starts with books on the topic, then reads reviews, and then digs down into research papers. As he goes, he summarizes everything he reads in a series of spreadsheets. His next step is to analyze those spreadsheets to identify gaps that he might fill.

The next part is his favorite, Alsbaiee says. He brings in collaborators to brainstorm ideas and score them on their synthetic difficulty, time commitment required, sustainability, scalability, and safety, as well as the availability and cost of materials.

Bryan Barton, who until recently led the CMP group at DuPont, says that an astonishing amount of planning and preparation set Alsbaiee apart early from other chemists—and paid off. “Alaaeddin focused on providing easily scalable and sustainable solutions, which are currently being developed into breakthrough products and will have an impact in the broader specialty polymer community,” Barton says.

Alsbaiee would eventually like to apply his system in a research leadership role. “I like to think about the strategic side of R&D projects,” he says. He’s also interested in building up the chemistry community. For example, since 2019, he has volunteered to translate some C&EN articles into Arabic with the goal of broadening access to science communication. He says the Arabic world is “eager to know more about science, about recent discoveries around the world and the exciting technologies that are being developed.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter