Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Discovery

Ziyang Zhang

Chemical biology champion is toppling tough drug targets with novel approaches

by Ryan Cross

August 20, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 30

Credit: Courtesy of Cindy Chew (Zhang); Protein Data Bank PDB ID 6WGN (protein); Science Source (T Cell)

Ziyang Zhang says he is a chemist at heart, but you would be hard pressed to find another scientist his age whose work stands poised to impact so many fields of medicine. At 30, he has already synthesized new potential antibiotics, targeted one of the most notoriously hard-to-drug proteins in cancer, investigated potential antivirals for COVID-19, and designed a new strategy for directing the immune system to attack tumors.

And he won’t even start his own lab until next year.

Advertisement

As a first-year PhD student at Harvard University, Zhang jumped on a project in Andrew G. Myers’s lab to devise a general strategy for the total synthesis of macrolides, a class of well-known and widely used antibiotics with complex structures. Chemists have traditionally made these antibiotics by modifying naturally derived macrolides—an approach that limits the potential diversity of new molecules. “They are not trivial to make from scratch,” Zhang says. But he found a way to do it.

Zhang co-led a team that divided macrolides into eight generic parts. By making several varieties of each of those eight parts and then stitching them together in different combinations, the team created hundreds of new macrolides. Many of them showed promise at killing bacteria resistant to commercial macrolides, and the work, published in 2016, formed the basis of a company called Macrolide Pharmaceuticals, now Zikani Therapeutics.

“He is one of the most amazing students that I have been privileged to supervise in 30 years,” Myers says. “He is an incredibly talented organic chemist.”

For his postdoc, Zhang joined chemical biologist Kevan Shokat’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco. There, Zhang has devised multiple ways to drug mutant forms of KRAS, a protein commonly implicated in cancer.

Shokat’s lab had previously developed a small-molecule inhibitor of KRAS G12C, a mutant in which a glycine has been replaced by a cysteine. But a form of the protein in which the same glycine is replaced by an aspartate—a G12D mutation—had proved particularly devilish to drug. The mutation is frequently found in pancreatic cancers. To Shokat’s amazement, Zhang discovered a G12D inhibitor in about a year.

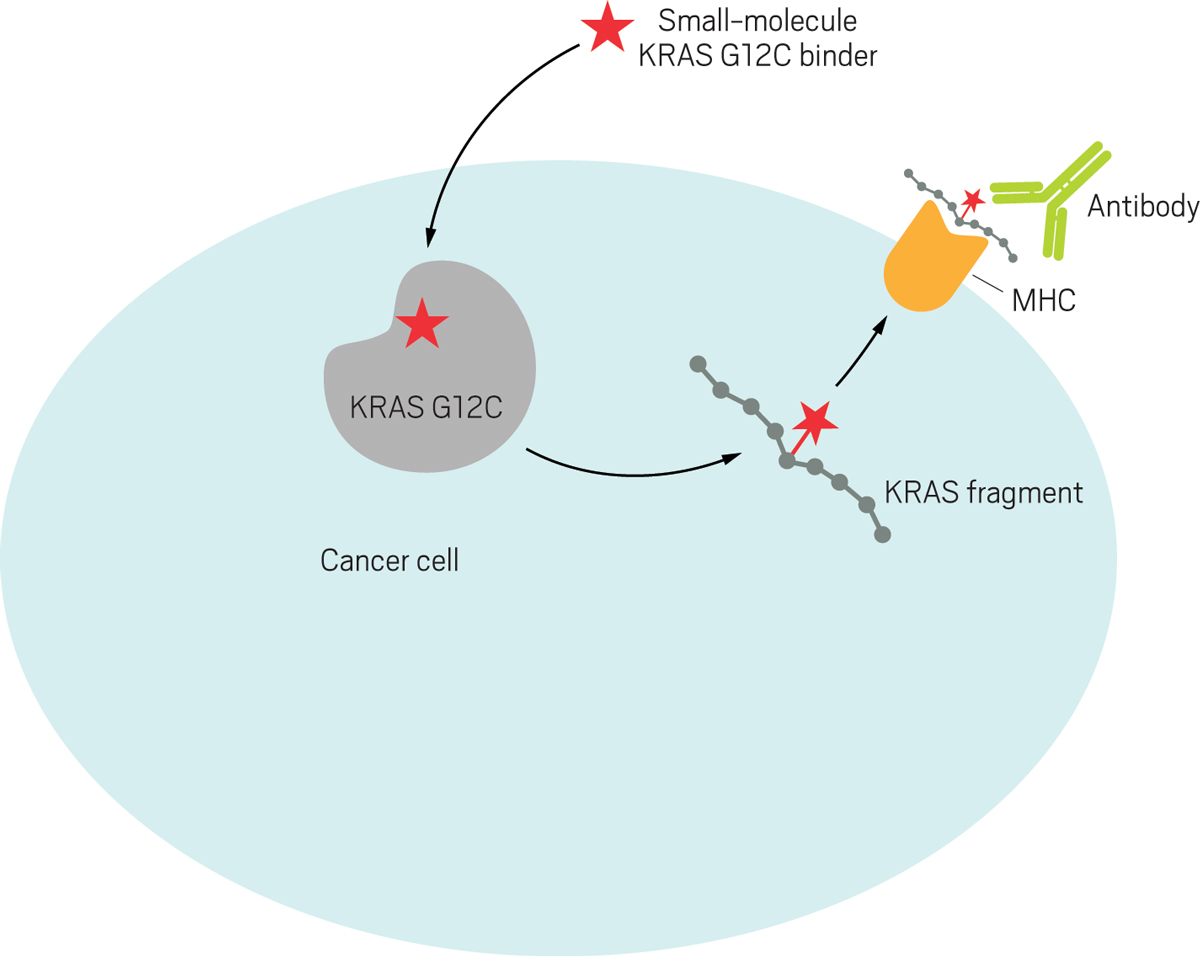

Zhang also created a new strategy for recruiting the immune system to attack cancers with the G12C mutation. The approach relies on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, which Zhang compares to “little hands” that sit on the surfaces of cells and hold up snapshots of proteins found inside.

First, Zhang covalently tagged the reactive cysteine in G12C with a small molecule based on Shokat’s earlier work. Next, he showed that fragments of the KRAS protein are displayed by MHC molecules on the surfaces of cancer cells, with the covalent small-molecule flag still attached to G12C. Finally, Zhang made antibodies that target that small-molecule flag and recruit T cells of the immune system to swoop in and kill the cancer cell.

The discovery is timely because doctors have recently seen tumors develop resistance to G12C inhibitors. Shokat says the approach “could lead to cures” for some cancers—a statement that he doesn’t make lightly. And Zhang hopes to generalize the strategy and apply it to other proteins beyond KRAS. The work, which is still unpublished, is already attracting the attention of biotech companies. Zhang will take the project with him when he starts his own lab at the University of California, Berkeley, next year.

As if his KRAS projects weren’t enough to fill his time as a postdoc, Zhang also devised a new method for selectively delivering kinase inhibitors into the brain while minimizing side effects in the rest of the body. And during the pandemic, he worked on multiple projects related to drug discovery and drug repurposing for COVID-19.

Zhang says that when he starts his independent career, he plans to “use chemistry to help us understand the immune system and to make our immune systems work better”—either by attacking cancer or by preventing autoimmune disease.

Vitals

Current affiliation: University of California, San Francisco

Age: 30

PhD alma mater: Harvard University

Hometown: Taizhou, China

If I were an element, I’d be: Carbon. “The same element that builds the strongest material and the most vivid life on earth. Plus, carbon grills make the best BBQs.”

Role model: “As the old Chinese saying goes, ‘三人行, 必有我师焉’ (There is always something to learn from my companions). I think of all my past and present mentors as my role models in some way. I want to specially mention professor Lianyun Duan (Peking University), who was my chemistry olympiad coach in high school.”

Ziyang Zhang says he is a chemist at heart, but you would be hard pressed to find another scientist his age whose work stands poised to impact so many fields of medicine. At 30, he has already synthesized new potential antibiotics, targeted one of the most notoriously hard-to-drug proteins in cancer, investigated potential antivirals for COVID-19, and designed a new strategy for directing the immune system to attack tumors.

And he won’t even start his own lab until next year.

As a first-year PhD student at Harvard University, Zhang jumped on a project in Andrew G. Myers’s lab to devise a general strategy for the total synthesis of macrolides, a class of well-known and widely used antibiotics with complex structures. Chemists have traditionally made these antibiotics by modifying naturally derived macrolides—an approach that limits the potential diversity of new molecules. “They are not trivial to make from scratch,” Zhang says. But he found a way to do it.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: University of California, San Francisco

▸ Age: 30

▸ PhD alma mater: Harvard University

▸ Hometown: Taizhou, China

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: Carbon. “The same element that builds the strongest material and the most vivid life on earth. Plus, carbon grills make the best BBQs.”

▸ Role model: “As the old Chinese saying goes, ‘三人行, 必有我师焉’ (There is always something to learn from my companions). I think of all my past and present mentors as my role models in some way. I want to specially mention professor Lianyun Duan (Peking University), who was my chemistry olympiad coach in high school.”

Zhang co-led a team that divided macrolides into eight generic parts. By making several varieties of each of those eight parts and then stitching them together in different combinations, the team created hundreds of new macrolides. Many of them showed promise at killing bacteria resistant to commercial macrolides, and the work, published in 2016, formed the basis of a company called Macrolide Pharmaceuticals, now Zikani Therapeutics.

“He is one of the most amazing students that I have been privileged to supervise in 30 years,” Myers says. “He is an incredibly talented organic chemist.”

For his postdoc, Zhang joined chemical biologist Kevan Shokat’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco. There, Zhang has devised multiple ways to drug mutant forms of KRAS, a protein commonly implicated in cancer.

Shokat’s lab had previously developed a small-molecule inhibitor of KRAS G12C, a mutant in which a glycine has been replaced by a cysteine. But a form of the protein in which the same glycine is replaced by an aspartate—a G12D mutation—had proved particularly devilish to drUg. The mutation is frequently found in pancreatic cancers. To Shokat’s amazement, Zhang discovered a G12D inhibitor in about a year.

Zhang also created a new strategy for recruiting the immune system to attack cancers with the G12C mutation. The approach relies on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, which Zhang compares to “little hands” that sit on the surfaces of cells and hold up snapshots of proteins found inside.

First, Zhang covalently tagged the reactive cysteine in G12C with a small molecule based on Shokat’s earlier work. Next, he showed that fragments of the KRAS protein are displayed by MHC molecules on the surfaces of cancer cells, with the covalent small-molecule flag still attached to G12C. Finally, Zhang made antibodies that target that small-molecule flag and recruit T cells of the immune system to swoop in and kill the cancer cell.

The discovery is timely because doctors have recently seen tumors develop resistance to G12C inhibitors. Shokat says the approach “could lead to cures” for some cancers—a statement that he doesn’t make lightly. And Zhang hopes to generalize the strategy and apply it to other proteins beyond KRAS. The work, which is still unpublished, is already attracting the attention of biotech companies. Zhang will take the project with him when he starts his own lab at the University of California, Berkeley, next year.

As if his KRAS projects weren’t enough to fill his time as a postdoc, Zhang also devised a new method for selectively delivering kinase inhibitors into the brain while minimizing side effects in the rest of the body. And during the pandemic, he worked on multipleprojects related to drug discovery and drug repurposing for COVID-19.

Zhang says that when he starts his independent career, he plans to “use chemistry to help us understand the immune system and to make our immune systems work better”—either by attacking cancer or by preventing autoimmune disease.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter