Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Infectious disease

Covid-19

Can you get COVID-19 in the bathroom?

Scientists have been studying how toilet flushes spread viruses like SARS-CoV-2 for decades, and they still don’t have clear answers

by Laura Howes

October 4, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 38

As we try to navigate our daily routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us are concerned with how to reduce our risk of exposure to the novel coronavirus. One activity we can’t avoid is going to the bathroom. If a person infected with SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—uses the bathroom before you, what is your risk of getting infected?

When passing from person to person, viruses don’t move about on their own. They often hitch a ride in droplets like those produced when you speak or cough, and those droplets can also produce smaller aerosols that float several meters through the air. Over the years, scientists have studied whether aerosol sprays from toilets might also spread pathogens like SARS-CoV-2. They’ve found that toilet flushes can indeed make aerosols containing viruses. But they are still trying to determine whether you can get sick from breathing them in.

Although most people with COVID-19 have fever, cough, and trouble breathing, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also lists gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea. Researchers have found the virus in the feces and urine of people with COVID-19 (Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020, DOI: 10.3201/eid2608.200681; Emerging Microbes Infect. 2020, DOI: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1760144) and detected the virus’s RNA in toilets and sewers. There haven’t been any confirmed cases of people catching COVID-19 through exposure to the virus from feces or urine. But some researchers—and many people who need to find a bathroom while on the road—wonder if public toilets pose an infection risk.

Earlier this year, Yun-Yun Li, Ji-Xiang Wang, and Xi Chen at Southeast University were concerned about this exact question and used computational fluid dynamics models to determine how flushing the toilet can drive water from the toilet bowl into the air. According to their model, a flushing toilet generates a cloud of thousands of aerosol droplets that rises about a meter into the air if the lid is up (Phys. Fluids 2020, DOI: 10.1063/5.0013318). They also modeled how urinal flushing can produce aerosols (Phys. Fluids 2020, DOI: 10.1063/5.0021450). These weren’t the first studies to show that flushing generates aerosols, but the researchers hoped their models might nudge the public to consider bathroom hygiene more during the pandemic.

Support nonprofit science journalism

C&EN has made this story and all of its coverage of the coronavirus epidemic freely available during the outbreak to keep the public informed. To support us:

Donate Join Subscribe

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in the air. According to Kaisen Lin, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis, Air Quality Research Center, liquid aerosols don’t stay liquid forever. Some droplets fall onto surfaces, but “over time, when they stay airborne for long enough, the water evaporates and they become droplet nuclei,” he tells C&EN in an email. These droplet nuclei are small, dry particles that are light and can remain airborne for long periods of time.

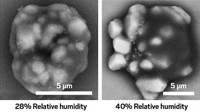

Aerosols, whether they’re generated from a person’s cough or a flushed toilet, can carry bacteria or viruses. Virologists often define infectious aerosol particles as those under 5 µm in diameter, but droplets up to around 60–100 µm can also stay suspended in the air and carry microbes. Factors including temperature, humidity, the presence of ultraviolet light, and the type of microorganism can affect how long the pathogen can survive in the air and still infect a person, Lin says. But in general, viruses in liquid aerosols seem to struggle to survive at intermediate humidities—those of about 55%. Under those conditions, the liquid in the aerosols evaporates slowly, giving the increasing concentration of salts and other solutes time to disrupt the virus structure (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b04959).

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, laboratory studies by other researchers have shown that the virus can survive intact in liquid aerosol droplets for hours (N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973; Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020, DOI: 10.3201/eid2609.201806). And outbreaks that have been traced back to indoor spaces where people maintained social distancing, such as an outbreak from a choir practice in Skagit County, Washington, in March, have contributed to a growing body of evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can spread through the air, possibly through long-lived aerosols.

Scientists haven’t found direct evidence that toilet aerosols can spread viral diseases, but they have been studying the germy plumes caused by flushed toilets since at least the 1950s. Over time, they have refined their experimental setups to try to get a more accurate picture of how infectious the aerosols might be.

In some early experiments, researchers left agar plates surrounding flushing toilets. Any bacteria or viruses that fell out of the air could then grow on the plates, allowing researchers to determine what the toilet aerosols carried. However, according to Lin, this form of passive sampling has a downside: “The concentration of bacteria or virus in the air is usually low,” and sometimes not enough of a pathogen lands on the plates to be detected. “To effectively collect airborne microorganisms, a better idea is to use a pump to pull air from a room through a filter,” he says. This method allows researchers to collect more of the microbes in the air in a short period. These days, such air samplers can be wheeled into different rooms, and scientists can then capture intact viruses or use polymerase chain reaction–based methods to identify the genetic material of viruses collected. But these all require subsequent laboratory steps.

While a PhD student in Linsey Marr’s group at Virginia Tech, Lin used some of these techniques to understand how the Ebola virus might spread through fecal aerosols, including from flushing toilets. In one experiment, he put decontaminated sewage sludge dosed with phages (viruses that infect bacteria) into a toilet at the university and then measured what came back up when he flushed. He and Marr found that although flushing sent only a small amount of virus into the air, the microbes could survive the process and remained infectious (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04846).

Outside the lab, some researchers have studied cases that suggested people had been infected by aerosols from feces. For example, Yuguo Li, an expert in indoor air quality at the University of Hong Kong, investigated a case from the COVID-19 pandemic earlier this year.

Since 2003, Li has worked with health professionals to investigate various outbreaks of infectious disease, including the 2002–3 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. Back then, over 300 people became infected with SARS in an apartment complex in Hong Kong known as Amoy Gardens. Li and colleagues thought that fecal aerosols from a broken sewage pipe could have caused the outbreak (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867).

Fast-forward to February 2020, and Li was working with the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention to investigate the origin of some cases of COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China. Nine people living in three apartments in a high-rise building had COVID-19. While one family had recently returned from Wuhan, then the epicenter of the pandemic, the other families had not. Contact tracing couldn’t explain how the other families got infected. But while all the sick families lived on different floors, their apartment numbers all ended in 02, meaning they lived in apartments above one another, and they all shared the same sewage pipe system. Li and the investigating team wondered if something similar to Amoy Gardens was to blame in the Guangzhou building. The Chinese CDC took swabs of shared areas in the building and set up aerosol samplers around the apartments, but it found no virus in the air. “I believe that the virus-containing aerosols had already gone before their sampling,” Li writes in an email to C&EN.

To determine if the sewage system could have spread the virus, the researchers added small amounts of ethane gas to the pipes through a toilet in one of the infected families’ apartments. The ethane ended up in all three of the apartments (Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, DOI: 10.7326/M20-0928). Because of these results, along with data from fluid dynamics modeling, Li’s team concluded that fecal aerosols from the first infected family may have traveled through the shared sewage lines and into the other apartments through dried-out drains.

So far, evidence from scientists studying SARS-CoV-2 suggests that the hot spots for catching the virus are confined spaces, places where you are in close contact with others, and crowds. Li agrees that those places should be avoided. But he points out that restrooms are, naturally, confined spaces.

When you gotta go, you gotta go. So what should people do to reduce their risk? Several researchers at a virtual workshop on the airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 held by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in August suggested that in all shared indoor spaces, people should wear masks to reduce the spread of the disease by respiratory droplets and aerosols. Also, the rooms should be well ventilated, and surfaces should be cleaned regularly. The Southeast University scientists who modeled toilet and urinal flushes agree with the mask advice; they think the masks can also protect the wearer from far-traveling aerosols caused by flushing. However, during a panel session as part of the National Academies workshop, University of Leicester virologist Julian Tang pointed out that while flushing with the lid up will expose you to aerosolized pathogens that you might breathe in, it isn’t clear how much you have to inhale to become infected.

More importantly, the experts agree that the rules for good toilet hygiene remain the same. If there is a lid, always put it down before you flush, and wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water afterward. You were doing that after going to the bathroom already, right?

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter