Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Labs made advances in Zika research

Although funding to fight the virus was stymied, scientists hit milestones

by Sarah Everts

December 14, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 49

In January, the Pan American Health Organization announced an alarming rise in cases of microcephaly and other birth defects among newborns in Brazil, a trend that seemed to coincide with the spread of Zika virus-infected mosquitoes across the country. Shortly thereafter, the World Health Organization declared the Zika virus outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern.”

In the U.S., the Obama Administration requested $1.9 billion from Congress in February to fund development of Zika vaccines and diagnostics, as well as to find new strategies to control the virus’s mosquito vectors.

But political bickering stalled approval for seven months and forced federal agencies to perform accounting acrobatics to address the health threat. For example, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention shifted allocations from Ebola research into Zika accounts. Finally, in late September, Congress approved $1.1 billion in stop-gap funding to battle Zika—what many health advocates worried was too little, too late.

“Despite the funding included in the bill, the U.S. response to the Zika crisis remains woefully restricted and inadequate,” opined Nina Besser Doorley of the International Women’s Health Coalition. “The United States failed to act until Zika reached its shores and is trying to catch up.”

Meanwhile, rivals in the publishing industry—Science, Nature, the New England Journal of Medicine, and others—put politicians to shame as they agreed jointly in February to make all Zika-related research articles available for free.

As the year wore on, evidence of Zika’s impact on developing fetuses mounted. By summer, most scientists concurred that the mosquito-borne virus was crossing the placental barrier in pregnant women and interrupting healthy fetal brain development.

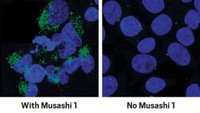

A flurry of work in laboratories around the world resulted in many milestone advances: Scientists sequenced the genome of the epidemic’s virus, solved the three-dimensional structure of the virus’s protective protein shell, tracked how Zika crosses the placenta, identified potential host and viral proteins involved in infection, and performed initial screens for molecules that might prevent this interaction.

Although much work remains to protect pregnant women and their unborn babies, there’s cause for cautious optimism: A dozen diagnostic tools to identify the pathogen and several Zika vaccines are currently being tested on humans in the clinic.

C&EN's YEAR IN REVIEW

Top Headlines of 2016

- Hawaii explosion cost a researcher an arm

- TSCA reform crossed the finish line

- U.S. elected Trump as president

- The periodic table got four new elements

- Post Dow-DuPont, chemical deal-making waned as 2016 advanced

- Labs made advances in Zika research

- Four ag giants to rule them all

- 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry at a glance

- Brexit bomb exploded

- Focus returned to Iran's chemical industry

- Overtime pay limit doubles under Obama administration

- The CRISPR craze continued

- Perfluorinated compounds got increased scrutiny

- From the lab to the market

- Paris Agreement to curb climate change took off

- World chemical production at a glance

- Flint's water woes lingered

- As China's economy slowed, chemical makers adjusted

- Mostafa A. El-Sayed won the 2016 Priestley Medal

- ACS members on average fared better than young graduates in employment surveys

- ACS invests internationally

- Spun-off firms found their footing in 2016

- Remembering the Nobel laureates we lost in 2016

- ACS proposed chemistry preprint server

- Berkeley College of Chemistry avoided reorganization

- Fight against opioid epidemic continued in 2016

- Noble gas shortages averted, for now

- The shale gas boom by the numbers

- Crop protection products in the crosshairs

- ACS launched new journals

- Website search terms of the year

- Biobased materials hit the big time

- No better deal emerged for Mossville, La.

- U.S. prepares for national food labeling standard

Top Research of 2016

- Mini factory made drugs on demand

- World's first PET-munching microbe discovered

- Liquid metals went to work

- Methylene activation reached new heights

- Biological structures of the year

- Wearable sensors were 'the' fashion accessories of 2016

- Scientists beefed up the antibiotic arsenal

- An enzymatic route to carbon-silicon bonds

- Single-atom catalysts gained a toehold

Revisiting Research of 2006

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter