Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Nanocar Research Kept Rolling Along

Molecular Machines: ‘Vehicules’ continued to inspire scientists, even if practical applications still seemed far off

by Bethany Halford

December 21, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 49

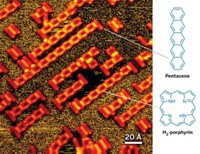

Big pickup trucks, such as those in Ford’s F-Series, were the best-selling automobiles in the U.S. in 2005. But that same year, chemists unveiled a considerably smaller vehicle—the world’s first single-molecule car. Designed and driven by the research groups of Rice University’s James M. Tour and Kevin F. Kelly, respectively, the quirky ’05 coupe featured an oligo(phenylene ethynylene) chassis and axle covalently mounted to four fullerene wheels. Because the tiny vehicle’s wheelbase was less than 5 nm, the researchers dubbed it the nanocar (Nano Lett. 2005, DOI: 10.1021/nl051915k).

Tour tells C&EN that his original aim was fairly whimsical. He simply wanted to make a molecule that resembled an everyday object the general public would be familiar with. “This captures the mind of the nonchemist,” Tour explains. “This is where we take our chemistry and bring it into their world.”

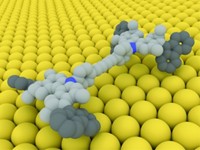

After that first report, scientists found nanocars have a higher purpose for studying how a molecule’s atoms interact with surfaces. Learning how to control that motion, Tour says, could help scientists do bottom-up molecular assembly, much like enzymes do, picking up atoms and putting them into place. “I think this is the way things are going to be built in the coming years,” he adds, “first starting with very small things, like memory on computer chips, and then moving to larger and larger things.”

In the past 10 years, Tour’s group has built a veritable fleet of vehicle-type molecules, or “vehicules.” Some have six wheels, some roll around on carboranes instead of fullerenes, and some include a light-driven molecular motor to push the nanocars forward with a paddle-wheel-like motion. The group’s latest vehicule is a 244-atom single-molecule nanosubmarine that whizzes around in solution (Nano Lett. 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03764).

Tour’s lab isn’t the only one making nanocars. Next fall, at least five different research groups will bring their nanocars to the Center for Materials Elaboration & Structural Studies at France’s National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) for the world’s first NanoCar Race. The vehicules will be propelled across a gold surface, four at a time, by electric fields from four scanning tunneling microscope tips that operate as part of a single instrument.

“The ultimate goal is to be able to understand how a surface at the atomic level interacts with a molecule,” says Eric Masson, a chemistry professor at Ohio University, who will race a supramolecular nanocar with a chassis that floats between cucurbituril wheels. “The nanocar is just a fun way to try to do this,” Masson says.

“Science is a step-by-step process,” adds NanoCar Race director and CNRS researcher Christian Joachim. “This is a way to show that science and technology can be for fun and that applications can develop years later.”

C&EN's YEAR IN REVIEW

Top Headlines of 2015

- Chemical Makers Looked To Big Deals

- NASA Got Up Close And Personal With Pluto

- Opposition To Neonicotinoids Intensified

- 2015 Nobel Prizes In Science At A Glance

- Climate Pact Clinched

- Little Good News For Chemistry Job Outlook In 2015

- Pfizer To Merge Again, This Time With Allergan

- Oil And Gas Industry Under Pressure

- Greening Up Fracking

- An Industry In Spin Cycle

- Finally, Emoji For Chemists

- A Big Deal For Chemists

- Tianjin Explosion Put Spotlight On Safety

- Women Assumed Leadership Roles At American Chemical Society

- Artificial Ingredients In The Crosshairs

- Jacqueline K. Barton, Unwavering Chemistry Champion

- House Science Committee Chair Pummeled Science Agencies

- NIST Veteran Became U.S. Government's Top Chemist

- Gene-Editing Technique Raised Ethics Questions

- World Chemical Production At A Glance

- Classroom Fires During Science Demonstrations Spark Concern

- Climate Was Right For Deal-Making

- American Chemical Society Dives Deeper Into Open Access With The Debut Of ACS Omega

- Lego Began Research On Switching To A Biobased Plastic

- New Chair Took The Helm At Troubled Chemical Safety Board

- Genetically Modified Foods In The Spotlight

- Overhaul Of U.S. Chemical Law Moved

- ACS Scholars Program Turned 20

- American Chemical Society Expanded Its Global Reach

- Scientists Called For Standardized Antibodies

Top Research of 2015

- Flexible Electronics You Can Inject

- Special Delivery For Sensitive Reagents

- Yeast Programmed For Opioid Total Synthesis

- Miracle Machine Builds Molecules On Demand

- Nickel Shines As A Catalyst

- 3-D Printing Takes On A New Dimension

- Atomically Thin Films Grow In Number

- Digging In The Dirt Yields Novel Bacteria Fighter

- Keeping GMOs On A Leash

- A Liquid With Holes In It

- Electron Microscopy Provides Unprecedented Close-ups

Revisiting Research of 2005

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter